Researcher creates AI-powered tools to outsmart hackers

Tiffany Bao is an assistant professor of computer science and engineering in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University. Bao has received a 2025 National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development Program (CAREER) Award for her work, which includes creating new AI tools that help software engineers find security vulnerabilities. Photo by Erika Gronek/ASU

In cybersecurity, the most dangerous threats are invisible.

A silent flaw. A forgotten bug. Code written years ago, waiting for the wrong person to discover it at the worst time.

An attack can unfold in minutes. Finding and fixing the weakness that let it happen? That can take months — if it's found at all.

According to the FBI, the agency receives more than 2,000 cybercrime complaints each day, with reported financial damages topping $16 billion annually. The professionals needed to stop them are in short supply. There are nearly 750,000 open cybersecurity jobs in the U.S. alone and 3.5 million worldwide.

This problem is exactly what Tiffany Bao is working to address.

Bao is an assistant professor of computer science and engineering in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University.

As a member of ASU’s cybersecurity faculty team, Bao is working hard to train students to fill the workforce pipeline. But while the shortage endures, she says we’ll have to address security threats not by hiring more humans, but by teaching computers to think like them.

For this work, Bao has received a prestigious 2025 National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development Program (CAREER) Award to support her bold research. Over the next five years, she and her team will develop a tool called SE-bot, a system designed to emulate the decision-making of elite cybersecurity experts.

Her goal? Make one of the most powerful and underused tools in software security accessible to anyone who needs it.

Maze running for machines

“Symbolic execution is incredibly useful,” Bao says. “But it’s complicated. You need a lot of experience and intuition to make it work. My research is about teaching computers to develop something like that kind of intuition on their own.”

Symbolic execution is at the heart of Bao’s innovative new work, and at its core is a way to look inside a program and ask: What could make this go wrong?

It works by treating inputs, things like usernames, commands or data files, as symbols. Then, it explores all the possible paths the software could take depending on those inputs, tracing every decision point along the way.

“It’s like a logic puzzle,” Bao explains. “Imagine a program is a maze. Symbolic execution tries every path through the maze to find the one that leads to a trap.”

But in the real world, software programs are enormous. Even a small application might contain thousands of branching points. Exploring every possibility becomes painfully slow. To manage that complexity, experts rely on instinct to make educated guesses about which paths to explore and which to skip.

“Human experts know where to look first,” Bao says. “We want to build a machine that can do the same thing, one day perhaps even better.”

Thinking like a hacker, minus the hoodie

With this new award, Bao is training SE-bot to learn from the best. She collected examples of how skilled analysts guide symbolic execution to find bugs and vulnerabilities. That data now forms the foundation for an artificial intelligence model capable of mimicking those expert moves.

What sets her work apart is that she’s not stopping at imitation. She’s building two versions of the SE-bot: a responsive bot that reacts to problems like a human would, and a proactive bot that sees trouble coming and adjusts its strategy ahead of time.

“It’s like the difference between hitting the brakes when you see a red light versus predicting that the light’s about to change,” she says. “The second one can save a lot more time and potentially a lot more systems.”

Both versions will be released as open-source tools. That means developers across the globe will be able to use them, adapt them and build on them.

“In computer science, we don’t want to reinvent the wheel,” Bao says. “But if we don’t share the wheel, then everyone has to build their own. Open-source research saves time, builds trust and helps everyone move faster.”

Empowering more people to protect more systems

Bao’s research could ultimately empower many kinds of software developers to do cybersecurity work. Instead of relying solely on specialists, SE-bot could help developers without a specific security background find vulnerabilities in their own code.

“We’re not trying to replace people,” Bao says. “We’re trying to give them better tools. Especially tools that let them do their jobs without needing a PhD in cybersecurity.”

This is especially important at a time when cybersecurity careers are critically understaffed. And while interest is high, the learning curve can be steep.

“Everyone thinks being a hacker sounds cool,” Bao says with a laugh. “But once you start learning, it can get overwhelming fast. You have to deeply understand how systems work before you can protect them. That’s why many students lose confidence.”

As part of her NSF-funded work, Bao and her colleagues will conduct programs to make cybersecurity education more fun and approachable. They’ll run and expand on high school summer camps, offered through the Center for Cybersecurity and Trusted Foundations, part of the Global Security Initiative. They will also host YouTube tutorials and continue to enhance teaching quality through pwn.college, a gamified cybersecurity training platform developed at ASU and used in more than 100 countries.

“We’re trying to build confidence through hands-on activities and instant feedback,” Bao says. “Capture-the-flag competitions and gamified exercises help students stay engaged and excited.”

Why universities must lead the charge

Projects like SE-bot are often too risky for private companies to take on. There’s no guarantee of success and little immediate profit. But the potential rewards, if successful, are enormous.

“Security isn’t something that makes companies money,” Bao says. “It’s something that helps them avoid losing money, so they tend to underinvest in it.”

That’s why institutions like ASU play a vital role. Universities take long-term bets on research that might not be commercially viable yet, but that could transform the field.

“This kind of high-risk, high-reward research is exactly what universities are built to do,” Bao says. “And ASU is especially good at it because we have such a strong, interdisciplinary cybersecurity team — from systems and software to human factors and AI.”

Ross Maciejewski, director of the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, agrees.

“Tiffany’s work is an outstanding example of research that has real-world impact,” he says. “She’s not just advancing the science. She’s creating tools, inspiring students and helping secure the systems we all rely on.”

More Science and technology

New research by ASU paleoanthropologists: 2 ancient human ancestors were neighbors

In 2009, scientists found eight bones from the foot of an ancient human ancestor within layers of million-year-old sediment in the Afar Rift in Ethiopia. The team, led by Arizona State University…

When facts aren’t enough

In the age of viral headlines and endless scrolling, misinformation travels faster than the truth. Even careful readers can be swayed by stories that sound factual but twist logic in subtle ways that…

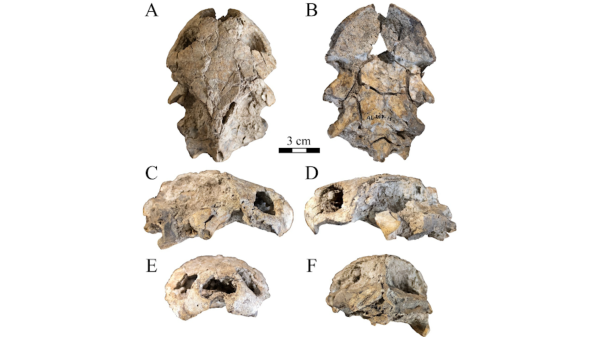

Scientists discover new turtle that lived alongside 'Lucy' species

Shell pieces and a rare skull of a 3-million-year-old freshwater turtle are providing scientists at Arizona State University with new insight into what the environment was like when Australopithecus…