Glass powder may be magic bullet in solving crimes

Assistant Professor Shirly Montero, of the School of Interdisciplinary Forensics, holds a bullet with white glass embedded between the lead slug and the copper metal jacket, in the ASU METAL Facility on the Tempe campus on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. ASU photo

Using shattered glass to glean clues from a crime scene is nothing new.

Broken pieces of glass can indicate where a criminal was standing, the angle of a bullet’s trajectory and, in the case of a drive-by shooting, it can even determine the direction of travel.

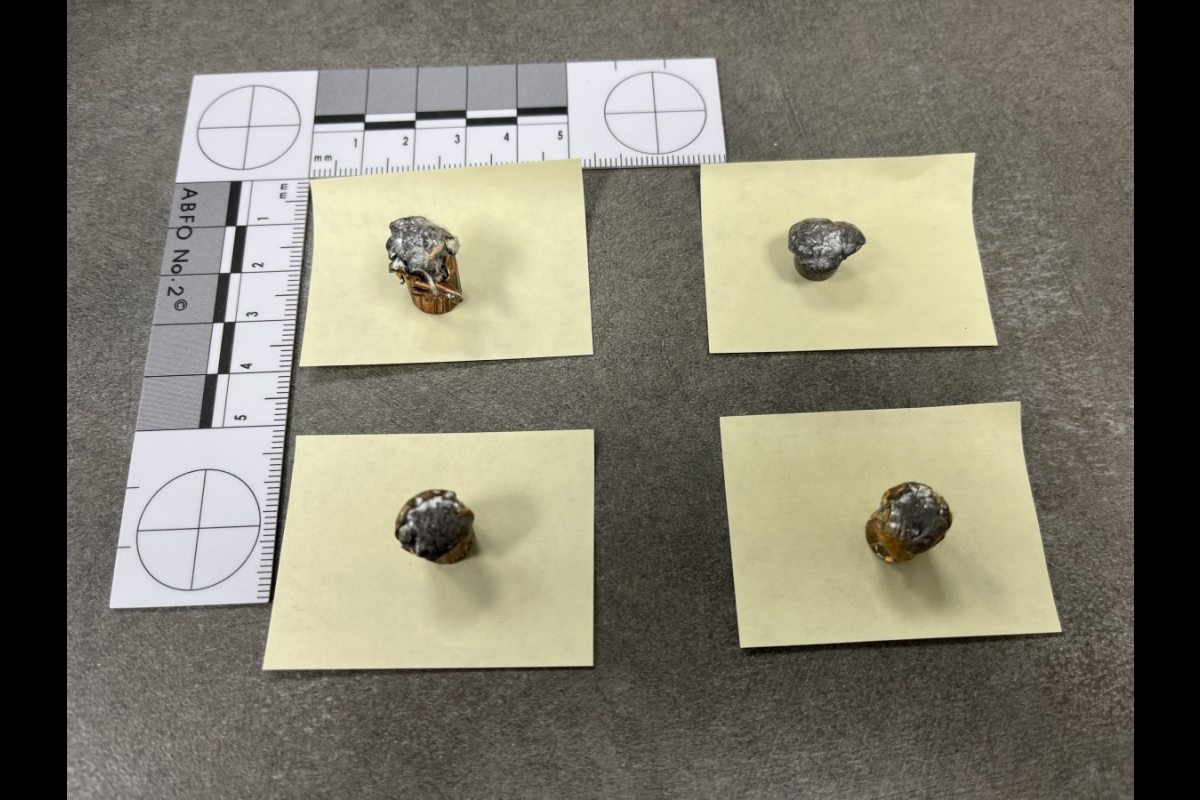

But what is new is the use of tiny pieces of glass embedded in a bullet, powder smaller than half a strand of hair, to help solve crimes.

That is what Shirly Montero is working on.

“We are pushing the boundaries by analyzing particles of smaller sizes than previously established,” said Montero, assistant professor in Arizona State University’s School of Interdisciplinary Forensics, at the West Valley campus.

Her technique will help when glass experts are analyzing a crime scene and don't have enough information to decide between one piece of glass and another.

“If you have multiple scenarios that are possible and all of them have a different source of glass as an intermediate target, you can use this technique to exclude some or all scenarios,” said Montero, who calls this approach “comparative analysis” — comparing the chemical make-up of one piece of glass to that of another.

Building a career around broken glass

Montero has studied glass for more than 25 years. Her research combines forensic chemistry, cognitive science, machine learning and more to create a comprehensive approach for improving the criminal justice system.

In recent years, she was inspired to research glass on bullets after a forensic firearms examiner approached her with a police-related shooting involving a driver in a vehicle.

“He wanted to know if glass embedded in a recovered spent bullet could be used as evidence to differentiate between two possible scenarios,” said Montero, who teaches forensic chemistry at the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences.

“If the police shot through the windshield, it could be justified as self-defense,” said the scientist. “A bullet coming through the passenger window meant that the shooting was unjustified.”

Breaking the glass ceiling

Montero is an expert glass analyst. She is a volunteer crime scene specialist for Mesa Police Department Forensic Services.

But examining microscopic pieces of glass embedded in a bullet takes this evidence-collecting technique to a new level — one that is still not a common crime-solving process for police detectives.

“We are one of the few labs that have the capability of doing this,” Montero said.

In order to take this process from the university lab to the crime lab, Montero must validate it with multiple studies of bullets supplied to her from firearm examiners and shooting reconstructionists.

“Right now, there is just not enough requests for this technique,” said Montero. “There are not enough studies that can assign value to the process for this application so it can be used in court.”

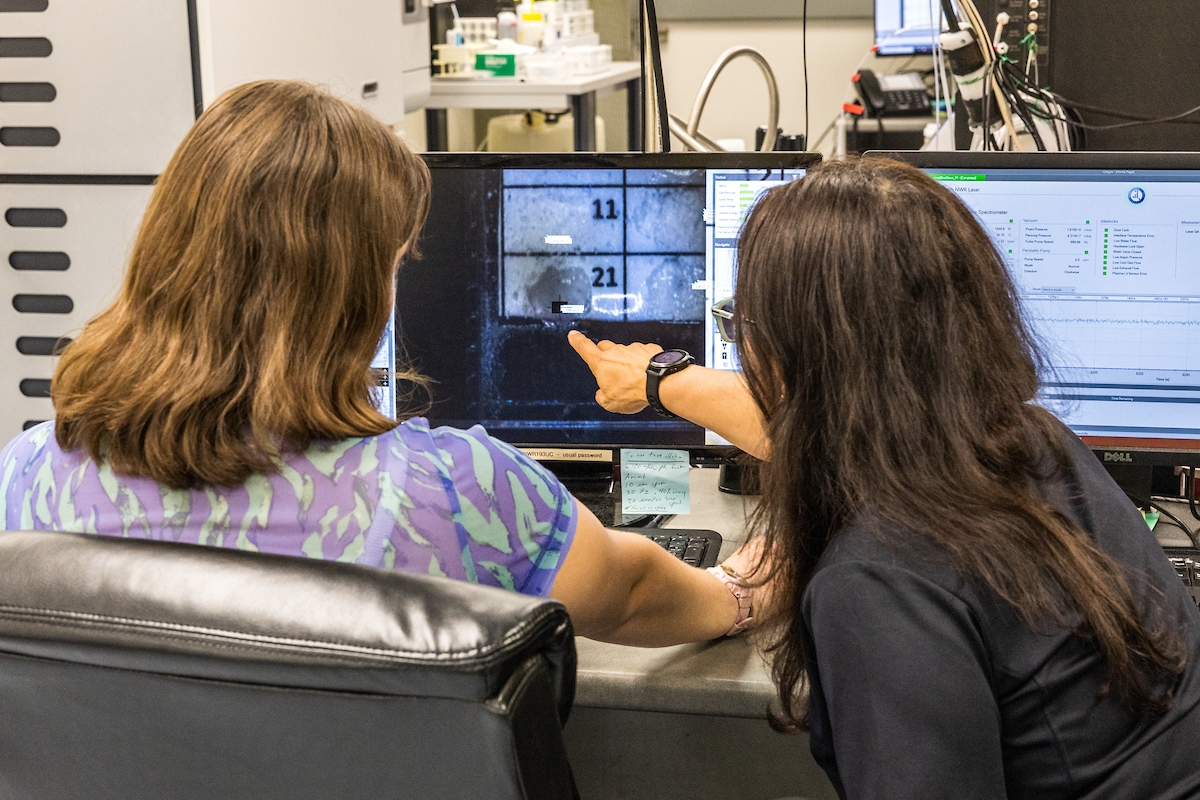

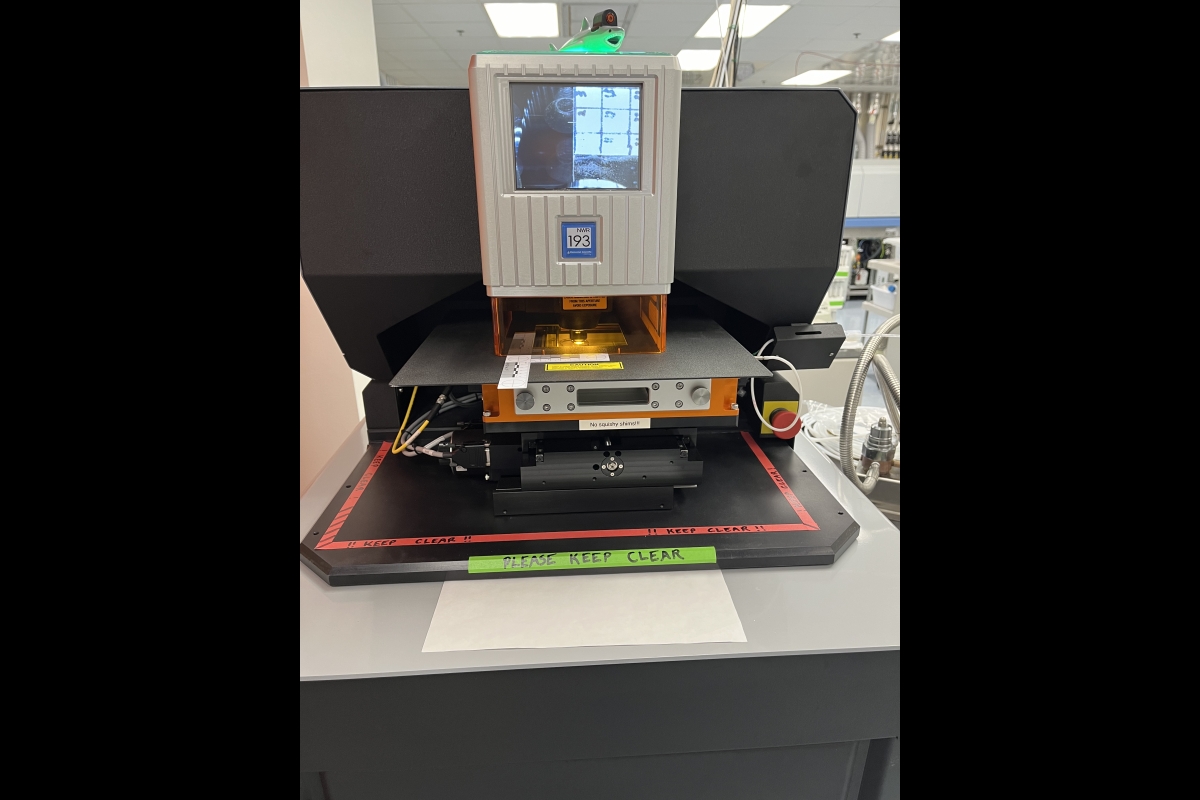

Montero is working to change that by gathering evidence of her own. Her current studies involve the use of what she calls the “gold standard” for analysis of glass evidence — a highly sophisticated laser ablation instrument and an ICP-MS (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer). Both machines are located in the Metals, Environmental and Terrestrial Analytical Laboratory, or METAL, on ASU’s Tempe campus.

The laser is used to remove a small subsample of the glass powder, which is then sent to the ICP-MS and used to measure 17 chemical elements in the profile of the glass sample.

“We can then use that profile to compare the glass on the bullet to different sources of glass that the investigator thinks could have been intermediate targets in the trajectory of that bullet,” Montero said. “We are analyzing embedded powder, and we are doing it with a robustness that will ultimately withstand the scrutiny of the courts.”

Montero has partnered with a software developer from Serva Energy, a local nuclear technology company with expertise in spectral analysis, to automate the signal processing step in the analysis of the glass.

She has presented work related to this research at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences conference and the Association of Firearm and Toolmark Examiners.

The results of her research will be available to firearms and shooting incident reconstruction experts before the end of the year. She hopes that one day it will be a regular part of the toolbox of techniques detectives use to solve crimes.

“Many times, forensic examiners are not making use of all of the valuable material at a crime scene,” she said. “My hope is to bring awareness of the technique of analyzing glass from bullets and support them in whatever scenario I can.”

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…