Pilot study shows first molecular links behind successful PTSD treatment

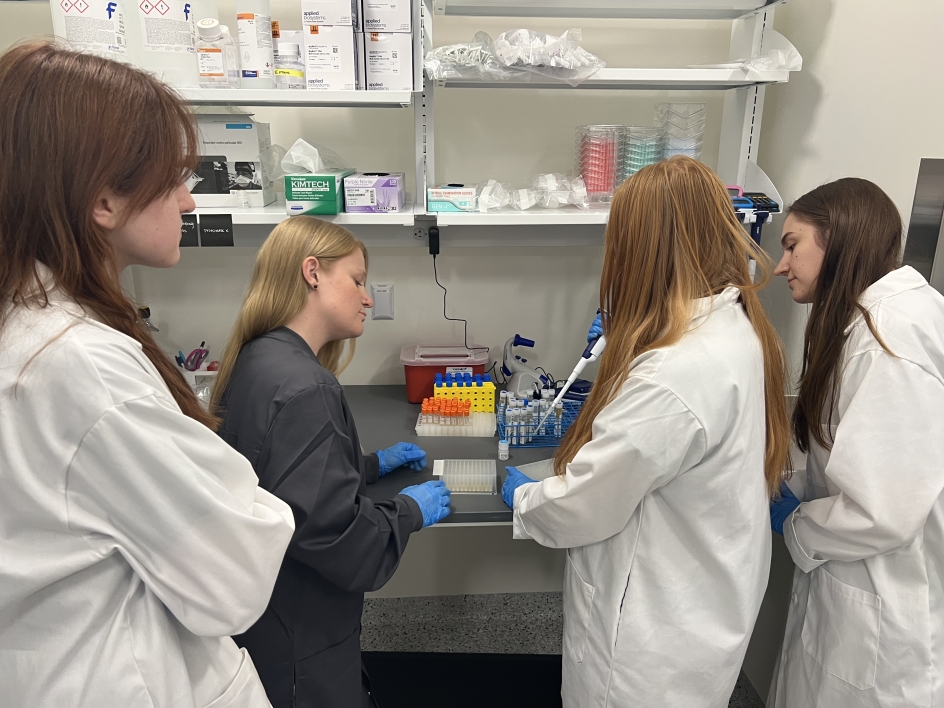

ASU School of Life Sciences researcher Candace Lewis (foreground) and her lab team explore the possible biological reasons for the role the psychedelic drug MDMA may be playing in the successful treatment of PTSD. Her lab includes the work of (back row, from left) neuroscience graduate student Allison Hays, BASIS Chandler High School senior Alyssa Ford and graduate psychology student Taena Hanson.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, affected an estimated 3.6% of Americans in 2022, with women (8%) and veterans (10% of males and 19% of females) experiencing even higher numbers. In fact, according to the National Center for PTSD, about 60% of men and 50% of women experience at least one severe trauma in their lives.

“Rates of childhood and adult trauma are high all around the world, even in the U.S.,” said Candace Lewis, an ASU School of Life Sciences assistant professor who is exploring the biological roots of people’s response to trauma and stress.

While most people have a resiliency to bounce back and resume daily activities in a few weeks or months, for some, PTSD can result in a severe and debilitating mental health condition that can require months or years of intervention and psychotherapy to return people to a sense of normalcy.

At the root of PTSD is trauma.

“Trauma comes in many forms, whether it’s childhood abuse/neglect, poverty, racial, combat or domestic partner violence — many of us are living with trauma,” said Lewis, who is also an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology. “For some, these experiences increase vulnerability to develop maladaptive behavioral and cognitive patterns. Stress-related disorders, such as PTSD, depression and anxiety — we can define them as maladaptive behaviors.”

PTSD is usually triggered by a terrifying event that is either experienced or witnessed. It can result in severe anxiety, flashbacks or nightmares that go on for months or years. For those requiring medical intervention, a groundbreaking treatment has been the drug 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or MDMA.

MDMA is not without controversy. It’s currently an illegal drug, popularly known as ecstasy or Molly. It became associated with the up-all-night rave culture starting in the early 1990s. More recently, the topic entered the public zeitgeist in 2018, with the runaway No. 1 best-seller “How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence” by Michael Pollan.

The book delved into the science of psychedelics and psychotherapy. And, after decades of anecdotal data of success from mental health professionals, MDMA has been fast-tracked for approval by the FDA — specifically for the treatment of PTSD.

For scientists like Lewis, this has also opened a new avenue of research to explore the possible biological reasons for the role that MDMA may be playing in the successful treatment of PTSD.

Lewis is trying to get at the data between behavior, mental health and our biological response to stress. To do so, she is examining in greater detail how experiences can alter the molecular regulation of systems involved in stress and mental health.

Now, she has completed a pilot study that shows the first molecular links behind successful PTSD treatment and new evidence that may explain the reasons behind its success.

Behavior and biology

Lewis wants to help revolutionize mental health treatment, grounded by the motivation of her own family experiences and the struggles of others.

“I grew up witnessing severe mental health problems,” Lewis said. “Data shows that this is becoming more and more common.”

She studies the impact of our social environments on molecules, all the way up to the brain and behavior, with the goal of making healthier lives for everyone.

“We don't know what we don't know yet,” Lewis said, “but your experiences have the ability to alter you at the molecular level that changes downstream gene transcription in a way that changes brain structure, function and behavior.”

An exciting new area linking experiences with behavior and biology is the field of epigenetics, which involves chemical modifiers that act as traffic signals to help modify the turning on or off of genes.

“The epigenome is referring to this infinitely complex regulatory system on top of our genome,” Lewis said. Research has shown that one’s experiences and exposures alter how genes are expressed through epigenetics.

Before returning to ASU to join the faculty, Lewis did her PhD work on behavioral neuroscience in the ASU Department of Psychology, at Professor Foster Olive’s lab. Her doctoral research examined how early experiences increase vulnerability to addiction. Lewis identified epigenetic markers of stress experienced early in life that increased drug intake in an animal model. She was also able to reverse the epigenetic markers in the model, which reduced drug intake behavior.

So, it was natural for Lewis to extend her research and wonder whether severe forms of PTSD could also be under epigenetic control.

The research team explores the molecular links behind biology and behavior. Photo courtesy Candace Lewis

Piloting downriver

Lewis relies on data from a large MDMA clinical trial run by researchers sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Lewis performed an epigenomic pilot study that examined a subset of 23 people for molecular clues to successful MDMA therapy for PTSD.

Recently, another colleague, Rachel Yehuda from Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine, reported positive results on the phase-three clinical trial, showing high efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapy for treating patients with severe PTSD compared with a placebo group.

Lewis and her research team found epigenetic changes in three key genes before and after MDMA and the placebo with therapy. All three genes are known to be implicated in the way humans respond to environmental perturbations with a stress response. They are major components of the homeostatic response in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, an intricate, yet robust, neuroendocrine mechanism that mediates the effects of stressors.

“The epigenome is referring to an infinitely complex genomic regulatory system,” Lewis said. “However, DNA methylation is the most commonly studied epigenetic mechanism, which is the covalent addition of a methyl (CH3) group to a CpG site.”

The CpG sites refer to two of the four chemicals/letter abbreviations that make up the rungs in the iconic model of the twisted-helical DNA ladder structure: the A, G, C or T nucleotides that make up the genetic code.

“A CpG site is a cytosine upstream of a guanine,” Lewis said. “CpG sites tend to cluster in gene promoter regions that need to be available for transcription and later translation into a protein product. These methyl groups are just a physical blockade of transcribing a gene.”

A CpG site acts like a red traffic light, telling the genome to stop making its protein products or, in this case, turning off the key genes involved in the stress response.

This study assessed DNA methylation levels at all 259 CpG sites annotated to the three HPA axis genes (CRHR1, FKBP5 and NR3C1). Importantly, the methylation changes only occurred across groups that significantly predicted symptom reduction on 37 of 259 CpG sites tested. In addition, the MDMA-treatment group showed more methylation change compared to placebo on one site of the NR3C1 gene.

“This gets back to the point of our CpG site lesson,” Lewis said. “We assessed CpG sites across the gene body, instead of only looking at the promoter region. While functional consequences of CpG methylation outside of the promoter is less understood, it may still be an important player in trauma — and treatment — response. It is not surprising that we found effects on NR3C1. If there ever was a famous gene, this glucocorticoid receptor would be it."

“Changes in glucocorticoid receptor gene expression from early life trauma was the first epigenetic finding that really initiated this field. Now, studies show epigenetic regulations of many genes are associated with mental health problems,” said Lewis. “Those who have experienced trauma are more likely to have a different expression of glucocorticoid receptors and a different cortisol profile than those who have not.”

Next steps

The findings of this study suggest that therapy-related PTSD symptom improvements may be related to DNA methylation changes in the HPA axis genes — and such changes may be greater in those receiving MDMA-assisted therapy.

“The results of the study are exciting and parallel findings from another psychotherapy study in PTSD,” said clinical trial director Yehuda. “More research is needed to fully examine how this new approach may be associated with epigenetic change to promote enduring transformation.”

Lewis is now turning to expanding and refining her pilot study results.

“Our ASU BEAR (Brain, Epigenetics and Altered States Research) Lab is interested in measuring epigenetic biomarkers for treatment response with various treatment options, including psilocybin, ketamine and, of course, a larger sample size with MDMA,” Lewis said. “We're also hoping it stimulates others to really start diving into biomarkers.”

With collaborators at ASU and other local institutes, Lewis is leading the charge on starting a research and clinical group focused on psychedelic-assisted therapies called Translational Research in Psychedelics (TRiP).

Talking about it

Lewis emphasizes that a better understanding of the biology behind MDMA treatment will further improve psychotherapy, and the time and experiences necessary for healing from a severe trauma experience.

“What I hope to convey as a take-home message is that healing has to be salient. ... Some patients need assistance to shatter the walls and cognitive barriers built around their traumatic experiences. For many people suffering from trauma, typical talk therapy may not penetrate them enough for real change. If one cannot talk about their trauma with a therapist and (is) struggling with mental health symptoms, then MDMA-assisted therapy may be a more efficacious treatment option for them.

"The psychopharmacology effects of MDMA are actually quite extraordinary: reduced anxiety, acute positive affect, increased insight, accelerated thinking and euphoria, and increased sense of trust and bonding. It’s in this state that patients are finding the ability to work through what it needed. It’s an intense experience; it’s intense healing.”

Lewis’ ultimate end goal is to turn psychotherapy on its head by asking: “If trauma is shaping the epigenetics that lead to an increase in symptoms, what can be such a healing experience that it shapes epigenetics in a way to decrease the symptoms?”

“People are hurting, right? There's a reason they have maladaptive behaviors and cognitive distortions. How do we help them? Surely we can do better than the current paradigm of chronic medication. I want to know, what do we need to heal? I am a neuroscientist, so I stick to data. I think that all output is biology, and experiences shape biology. We know we have trauma experiences, and I'm in search of the healing experiences. We sure are in need of them.”