Opening the door to chemical engineering

Arizona State University students (from left to right) Salma Ly, Julianna Joya and Ignazio Macaluso examine the chemical battery that will power their entry to the annual Chem-E-Car Competition hosted at the American Institute of Engineers, or AIChE, Annual Meeting. The students are members of the student organization AIChE at ASU. Photo by Hayley Hilborn/ASU

Arizona State University engineering students interested in networking and professional development opportunities need look no further than their local student branch of The American Institute of Chemical Engineers, or AIChE.

ALChE is a global network of chemical engineering professionals. With more than 60,000 members from 110 countries, AIChE offers its members access to a wide breadth of resources, including best practices for chemical engineering processes and methods, learning opportunities from recognized authorities and a community of colleagues to connect with.

Members in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering student branch of ALChE enjoy many of the same benefits as their professional counterparts, as well as hands-on activities to engage and enhance student abilities.

The most recent AIChE at ASU event was a joint event with student organizations the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and Material Advantage hosting EV Group. Up next is a research presentation by Jerry Lin, Regents Professor of chemical engineering in the School for Engineering of Matter, Transport and Energy, that will take place at 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 23, in the Engineering Center G-Wing G335 on the Tempe campus. Those interested in attending can RSVP here.

Developing professional relationships

AIChE at ASU members are encouraged to attend general monthly meetings to learn about upcoming opportunities and events. The student organization also hosts a variety of supplemental activities that cater to specific interests among its members.

Chapter President Matthew Hayes, a senior chemical engineering student, says AIChE programming works to build its members’ soft and technical skills. The group hosts industry professionals to lead activities like hiring events, resume-building exercises and day-in-the-life presentations where professionals map out what a typical day might look like for a chemical engineer.

AIChE at ASU’s executive committee has appointed two vice presidents: junior chemical engineering student Zachary Hargus, who manages external affairs, and Sumi Ramachandran, a senior chemical engineering student who manages the group’s internal affairs. Hargus connects with industry partners like Intel Corporation, EMD Electronics and, more recently, Tawain Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) for engagement opportunities.

“I wanted to expose chemical engineers to a variety of fields,” Hargus says. “Chemical engineering is extremely versatile. It can be applied in a lot of different ways, even within aerospace engineering or general sciences. I think that people should give a lot more thought to it because I actually had a lot of fun exploring the possibilities through internships I was offered through AIChE.”

While AIChE at ASU has diversified its pool of industry engagements, its next goal is to develop a relationship with a pharmaceutical company like PSC Biotech.

“We’re hoping to expand to different industries, as well as some companies outside of the state,” Hayes says.

The organization also works with faculty to host academic-related events where they can showcase their research and offer opportunities for student involvement.

“We try to push chemical engineering students to get involved in research pretty early on, and help them with that process,” Hayes says.

A professional advantage

Each year, the AIChE professional branch hosts an annual meeting that provides an educational forum for chemical engineers interested in innovation and professional growth. Last fall, the conference was hosted at the Phoenix Convention Center.

Abhinav Acharya, an assistant professor of chemical engineering and AIChE at ASU’s faculty advisor, says Hayes took the initiative to inspire fellow students to attend the in-person event following the pandemic.

“Matthew has shown great dedication to his peers’ success,” Acharya says. “He worked hours to help facilitate the 2022 AIChE Annual Student Conference, which was a part of AIChE’s Annual Meeting in Phoenix as the conference host school. He gathered more than 40 fellow undergraduate students to volunteer at the conference, enabling each of them to attend.”

Each annual meeting also hosts a Chem-E-Car Competition to engage college students in designing and constructing a car powered by a chemical energy source.

After years of being unable to compete due to the pandemic, AIChE at ASU participated in the 2022 competition with a team led by third-year chemical engineering student Salma Ly. Ly oversaw the group’s weekly meetings, where they worked together to construct the body of the vehicle and test the viability of its chemical battery.

Due to extenuating circumstances, the team was unable to compete at the national conference in 2022, but they are working diligently to develop a new vehicle that will compete in the regional competition in April 2023.

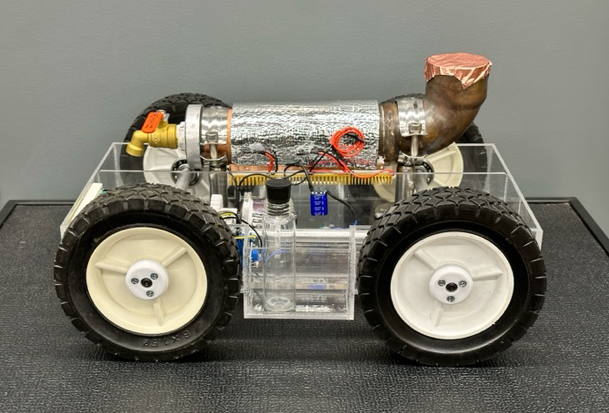

The AIChE at ASU team’s completed car entered in the 2022 Chem-E-Car Competition. Photo by Salma Ly/ASU

Why join AIChE at ASU?

“Being president of AIChE at ASU helped me improve my leadership abilities, presentation skills and my public speaking,” Hayes says.

He credits his connection to AIChE for helping him gain an internship with EMD Electronics. After graduating, he plans to pursue graduate studies in chemical engineering.

Hargus joined AIChE during his first year, when he was elected senator, and has held an officer position in the club since then. He says his early connection to the organization helped him establish his footing at the university and he encourages his peers to get involved as early as possible.

“I think a lot of people don’t run for officer positions because they think it will be a lot of work,” Hargus says. “And it definitely is, but people underestimate the reward. You get to work with more experienced students and you are exposed to industry and the inner workings of the organization early on. There’s a lot to learn.”

More Science and technology

Digital crimes leave data trails; these students built a tool to help explain them

In a courtroom, truth often hinges on storytelling. But when that story involves hex values, file systems, packet captures or…

From traffic systems to trustworthy AI, ASU students are solving problems the world can’t ignore

How do you trust artificial intelligence when it doesn’t know what it doesn’t know? How do you safely move computing systems…

Did the ribosome begin as a parasite?

The ribosome is one of life’s most remarkable inventions — a tiny molecular machine inside every cell that turns genetic code…