Army medic veteran, global health PhD student works to help homeless population

Richard Southee graduated with a master's degree in linguistics from Arizona State University. Photo courtesy of Richard Southee

Editor's note: This story is part of our Salute to Service coverage, Nov. 1–11. Learn about the schedule of events.

As a medic in the United States Army, Richard Southee was trained to deal with emergency medical situations that many civilian doctors may never encounter. However, it’s his work with mental health, trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder that has given him the most satisfaction.

Army Medic to higher education

Southee didn’t do well his first year in community college in Sierra Vista, Arizona, so he joined the military. Originally, he was planning on working in Army intelligence but ended up enlisting as a medic, which would change the course of his life.

“Transitioning from being a community college dropout to the military, it conditions you to work in high-stress environments to manage stress in a different way and to be focused,” Southee said. “I became very goal-oriented and centered because of the military.”

He went through basic training and was stationed at Fort Hood in Texas with the 69th ADA (Air Defense Artillery). Then he was stationed in Bahrain for nine months.

“As a medic, my role was to support this unit,” Southee said. “A lot of the work I was doing was not just in general health care, but was in mental health care. We had a lot of older soldiers who were dealing with PTSD, who were dealing with the consequences of being in the military for so long.”

After the service, Southee started taking pre-med courses as an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, but eventually found his passion in linguistics and Arabic.

As soon as Southee finished his undergraduate degree, he started his master’s degree in linguistics at Arizona State University. Southee was inspired by work Associate Professor Matthew Prior was doing as a discourse analyst with the ASU Department of English. While working under Prior for his master’s program, Southee also worked at ASU’s Pat Tillman Veterans Center.

Southee’s master’s thesis measured the cognitive burden of PTSD in veterans using speech patterns, Southee explained. He measured the burden by interviewing veterans and noting how many pauses were in each interview. Southee explained that pausing happens when your brain is working hard, and PTSD is work for your brain.

“My theory was that the worse the PTSD was, the more work their brain was doing,” Southee said. “So the harder it is, the worse the PTSD, and they would have a higher pause frequency in their speech.”

Because of COVID-19, Southee wasn’t able to get as much data as he hoped for, but his pilot study showed his theory to be correct. While working on his master’s degree, Southee was introduced to linguistic anthropologist Cindi SturtzSreetharan, who encouraged him to apply to PhD programs that could incorporate his work in health care, linguistics and trauma.

PhD work with the homeless population

Southee is currently a global health PhD student at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at ASU. He wants to use his experiences from the military, health care, linguistics and trauma to help make impactful changes in the nonprofit sector.

“As a PhD student, my research is on health care policy, homeless policy and trauma policy,” Southee said. “I look at how trauma influences the homeless and individuals' willingness to utilize services in general, but primarily health care services, with a subfocus on the unique aspects of veterans within this population.”

Southee said many times homeless veterans are resistant to utilizing resources because there is shame and the belief that others are more deserving. This culture of resisting support is established inside the military and continues into civilian life, said Southee.

“How do we reshape the work we are doing to account for and address the trauma this population is presently enduring because homelessness itself is traumatic?” Southee asked. “But also looking at all of the trauma they are carrying with them that likely contributed or led directly to homelessness.”

Southee said he was really drawn to working with the homeless populations when he started working for Central Arizona Shelter Services (CASS) during the pandemic while working on his master’s thesis.

Project Haven was started by CASS and the city of Phoenix to address the elderly homeless population most susceptible during the pandemic. Clients could stay at a hotel property in separate units with meals and security all on one site.

Southee started with CASS as a behavioral health case manager for Project Haven but is now the program success manager, which he hopes will help him to provide data that will make policies more trauma-informed.

“I just love working with this population,” Southee said. “Despite how hard of a situation they are in, I consistently saw my clients treating each other with grace and kindness, being upbeat and positive, looking out for each other, and generally tolerating a terrible situation better than I possibly could. Working at Project Haven I got to build close, personal relationships with these clients and learn about their lives before homelessness. Being homeless is a traumatic experience, and it can feel very encompassing of a person's identity, so it's difficult sometimes to remember these are whole people with real — often very interesting — stories.”

Southee hopes to continue his work with nonprofits and developing trauma-informed policies in leadership roles after obtaining his PhD.

More Health and medicine

First 2 degree offerings from ASU Health available in fall 2025

The first degree offerings from ASU Health will help students find jobs in the modernized health care system.The one-year…

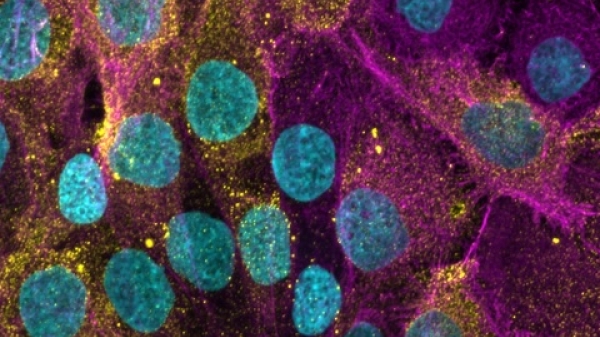

ASU study uses new biomaterials for wound healing

A minor cut often heals within days, vanishing without a trace. Yet, wound healing and tissue repair are complex biological…

Moeur awardee seeks to turn passion into tangible human impact

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable fall 2024 graduates.During high school, Nguyen Thien Ha Do,…