Nearly a quarter of all Americans either work from home or have flexible schedules that allow them to work remotely, according to a State of Remote Work 2021 poll.

It’s no longer a perk in a post-pandemic world. Instead, more Americans are simply demanding it from their employers.

While these workers enjoy this newfound freedom, they may still miss the office and need a sense of friendship and social activities, says an Arizona State University researcher.

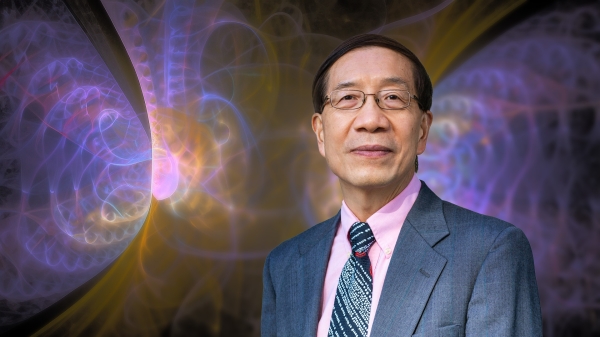

W. P. Carey School of Business Professor Blake Ashforth recently co-authored three related research papers on work-based identity and how best to support employees.

ASU News recently spoke to Ashforth, a Regents Professor and Horace Steele Arizona Heritage Chair in the Department of Management and Entrepreneurship, about remote work and work-place connections.

Blake Ashforth

Question: Your research paper, “My network, my self: A social network approach to work-based identity," has an interesting premise. How did you and your co-author, Jordana R. Moser, arrive at that conclusion?

Answer: Our work-related networks play a huge role in our work lives. We suspected their influence went beyond helping us find jobs, learning the ropes and supporting us as we worked through our problems. We suspected that they influence the way we come to think of ourselves, at least in the workplace.

Having a network of friends at work reinforces your friendliness and sense of being a friendly person; being part of a clique of movers and shakers suggests that you're an up-and-comer, and so on. This is especially true because we have more options in selecting network partners than coworkers or teammates. Choosing a particular network means you’re implicitly selecting a version of yourself to amplify.

Q: Given what you just said, how can employees find a place of identity in a hybrid or at-home workspace?

A: We’re adept at defining ourselves according to where we are and what we're doing. If you’re working from home, you’re still a professional, a teammate, an organizational member and a “virtual worker” — or whatever label you feel comfortable adopting. The trick, though, is feeling a real attachment to an organization, a team and coworkers. Work-based identities are more likely to take root in a virtual world if you have frequent and authentic interactions with people — preferably in informal and non-virtual contexts.

So, one organization we studied, which relied heavily on virtual work, did its best to bring people in periodically for work meetings but made sure to build in time for free-flowing social activities. The relationships they formed provided a lubricant for the inevitable frictions they encountered back in their teams while doing difficult projects together.

Q: Your second paper, which you wrote with Ronald H. Humphrey, “Institutionalized affect in organizations: Not an oxymoron,” is slightly different than the first. What can you tell us about this finding?

A: We tend to think of emotions and moods as fleeting. We argued that they could become baked into the DNA of a company. Companies have at least implicit affective cultures — a preferred way members should feel about certain things and how they should display those feelings. A retail outlet, for example, wants salespeople to be friendly and upbeat. At the same time, different employees react to challenging tasks, demanding clients and so on in similar ways such that an affective climate tends to bubble up from the bottom. The preferred culture and the actual environment then interact such that, over time, specific emotions and moods come to describe the true tone of the organization.

For example, newcomers can sense quickly if they're working in a place that seems tense, joyful or frustrating. The institutionalized affect, as we call it, becomes self-perpetuating. This matters significantly because shared affect influences how people interact, how well they do their jobs, whether they quit, etc.

Q: Your third paper, co-written with Daniel V. Caprar and Benjamin W. Walker, “The dark side of strong identification on organization: A conceptual review” is entirely different from your other two papers. Can you tell us the premise and give us an example of how that might look in the workplace?

A: Strong identification with your occupation, team or organization is usually very good. You care more and do what you can to fulfill that identity. But we argue that it becomes dangerous when you identify strongly but exclusively with any one target — at least in the work context. You become a one-note player and forget the other parts of yourself that should add richness and depth to who you are. It becomes all too easy to do unethical things on an organization’s behalf, get caught up in group tribalism and trash other groups, and jump to ill-considered conclusions.

The solution is not to identify less with that target but more strongly with other targets. You want to bring the well-known benefits of diversity into your thinking. Having multiple identities makes us wiser people.

Q: The common thread in these papers seems to be how we think about ourselves at work and feel about our work-place surroundings. Is there an overall message here for making organizations more effective?

A: We tend to think that effective management is largely about getting the incentives right. And people do respond to incentives. But what motivates them is having a sense of who they are, who they can be, and how they can realize this desired sense of self. Knowing these things provides clarity, meaning and direction. That's incredibly powerful. So, yes, pay and benefits matter, but the real incentives are those that let us realize our best selves.

Top photo courtesy Pixabay

More Science and technology

Extreme HGTV: Students to learn how to design habitats for living, working in space

Architecture students at Arizona State University already learn how to design spaces for many kinds of environments, and now they can tackle one of the biggest habitat challenges — space architecture…

Human brains teach AI new skills

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is rapidly advancing, but it hasn’t yet outpaced human intelligence. Our brains’ capacity for adaptability and imagination has allowed us to overcome challenges and…

Doctoral students cruise into roles as computer engineering innovators

Raha Moraffah is grateful for her experiences as a doctoral student in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University…