Mother, daughter to present personal perspectives at ASU incarceration conference

Photo by Luemen Rutkowski/Unsplash

Isabel Coronado was 7 years old when her mother, Sarai Flores, was arrested and later served one year at the Coffee Creek Women’s Prison in Oregon.

During this time, Coronado lived with her grandmother, and was only able to stay connected to her mother through a program that helps children and parents experiencing incarceration and teaches valuable parenting skills.

At the time, the program, Girl Scouts Beyond Bars, sponsored by the Girl Scouts of Oregon and Southwest Washington, was the only one of its kind. There were no other resources available to support children with incarcerated parents in Oregon.

Today, Coronado is an adult, and she and her mother, Flores, advocate for parents experiencing incarceration and their families. They are among the featured speakers at a national conference presented by Arizona State University’s Center for Child Well-Being.

The goal of the 4th annual Children of Incarcerated Parents National Conference is to create more awareness and advocacy for the children impacted by parental incarceration.

Flores became a teen mother at 17. By age 24, she was incarcerated.

“I had all that stigma growing up around having an incarcerated mother,” said Coronado, who is now 25. “I never really talked about it before publicly until I was in graduate school.”

Flores and Coronado will speak April 13 at one of three plenary sessions at the conference, a virtual event to be held on March 30, April 6 and April 13.

Click here to register and for more information on the conference’s offerings.

This year's theme, “Leading the Future: Young People as Partners for Change,” focuses on elevating the voices of children, youth and families whose lives have been impacted by incarceration, said Miguel Vieyra, a clinical associate professor in ASU’s School of Social Work (SSW) and interim director of the Center for Child Well-Being.

Vieyra said the conference’s plenaries, panels, focused sessions and workshops — many of which include young people and those who have lived experience as children whose parents are or have been incarcerated — will be organized into three main tracks:

- Understanding the effects of incarceration on children, youth, their families and caregivers.

- Connecting children, youth and families during and after incarceration.

- Supporting and centering the voices and experiences of children and youth.

More information on Coronado, Flores and other featured speakers at the conference can be found here.

Flores said that while she was away, no efforts were made to deny her parental rights. At that time, Coronado was cared for by her grandmother, but not all such children have relatives willing to do the same, she said.

“I don’t know how Isabel would have turned out if she were adopted,” Flores said. “About 14% of children of incarcerated parents end up in foster care.”

Today a law school graduate and advocate

The experience motivated Flores to alter her life’s direction, she said

“While I was in there, I really, really wanted to make a difference and make different decisions in my life,” Flores said. “What my time there did was allow me to question my motives about things, whether what I was doing was right or wrong. … Prior to that, I really didn’t do that. I just lived.”

Flores made several life changes since. After graduating from law school in 2011, she has held positions with the Muscogee Creek Tribe of Oklahoma and the U.S. Department of Energy. She writes and speaks about the intersection between mass incarceration, disability law, civil rights law and criminal justice reform.

Coronado has spoken often with media and the public about children with similar experiences. She is active in efforts to pass the Finding Alternatives to Mass Incarceration: Lives Improved by Ending Separation Act (FAMILIES) Act, proposed federal legislation that would enable parents who might otherwise be incarcerated to instead serve their time at home with their children.

Flores said society needs to know the importance of the relationship between these parents and children, and for the children to be involved in any progress their parents make.

“Telling my story is really hard for me, and it’s hard to talk about it and be vulnerable,” Flores said. “But I think that it’s important for anyone who interacts with those who are incarcerated to be trauma-informed.”

More support and programming are needed to ensure the social and emotional well-being of children and their parents, Flores said, as well as further the bond between parent and child, which facilitates a more successful reentry for parents experiencing incarceration.

The conference isn’t only for social service providers, but teachers, librarians, school counselors, philanthropists, health care professionals, child care professionals and others who interact with children and families, because parental incarceration is a common experience in the United States, said School of Social Work Associate Director for Academic Affairs Judy Krysik. Krysik, an School of Social Work associate professor, oversaw the conference through 2021 as the Center for Child Well-Being 's former director. Both the School of Social Work and the and Center for Child Well-Being are based in the Watts College of Public Service and Community Solutions.

Conference aims to keep issue before public

Krysik said the center hosts the conference each year to keep this issue front and center and to encourage action, whether through policy change or the development of programs and services to better support children and families affected by incarceration.

“People should attend to hear, directly from those affected, what it is like to have a parent who is incarcerated, and what people can do to assist them,” she said.

Attendees should leave the conference with several takeaways, Krysik said:

- Greater empathy.

- Ideas for how to run a social support group in a school or university.

- How to tailor physical spaces so that they are more child friendly when a child visits their parent.

- How to use books to communicate with children and youth about the experience in an effort to reduce shame and stigma.

- How to conduct parenting programs for women and men experiencing incarceration, and much more.

“Maybe most important, people can learn about the resilience of children and youth, and how so many have turned their pain into advocacy and service to help those currently and formerly impacted,” Krysik said.

More Arts, humanities and education

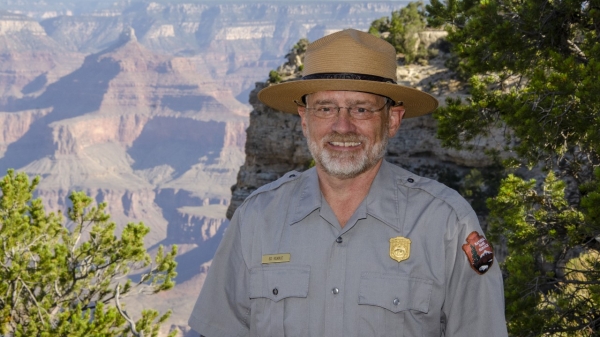

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk…

Honoring innovative practices, impact in the field of American Indian studies

American Indian Studies at Arizona State University will host a panel event to celebrate the release of “From the Skin,” a…