Machine learning identifies mammal species with the potential to spread SARS-CoV-2

Insights can guide surveillance to prevent secondary spillover, new variants

Arvind Varsani is a virologist at the Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics and a researcher in the Center for Evolution and Medicine and the School of Life Sciences at ASU.

Back-and-forth transmission of SARS-CoV-2 between people and other mammals increases the risk of new variants and threatens efforts to control COVID-19. A new study, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, used a novel modeling approach to predict the zoonotic capacity of 5,400 mammal species, extending predictive capacity by an order of magnitude. Of the high-risk species flagged, many live near people and in COVID-19 hot spots.

A major bottleneck to predicting high-risk mammal species is limited data on ACE2, the cell receptor that SARS-CoV-2 binds to in animals. ACE2 allows SARS-CoV-2 to enter host cells and is found in all major vertebrate groups. It is likely that all vertebrates have ACE2 receptors, but sequences were only available for 326 species.

To overcome this obstacle, the team developed a machine learning model that combined data on the biological traits of 5,400 mammal species with available data on ACE2. The goal: to identify mammal species with high "zoonotic capacity" – the ability to become infected with SARS-CoV-2 and transmit it to other animals and people. The method they developed could help extend predictive capacity for disease systems beyond COVID-19.

The study was led by researchers at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. They are joined by João P.G.L.M. Rodrigues of Stanford University and Arvind Varsani of Arizona State University.

Varsani, a virologist at the Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics who contributed to the assembly of sequence data used in the study, commented, “This is a significant research outcome from a multidisciplinary team that includes animal and disease ecologists, structural biologist and a molecular and evolutionary virologist.”

Co-lead author Ilya Fischhoff, a postdoctoral associate at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, commented, “SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, originated in an animal before making the jump to people. Now, people have caused spillback infections in a variety of mammals, including those kept in farms, zoos and even our homes. Knowing which mammals are capable of reinfecting us is vital to preventing spillback infections and dangerous new variants.”

When a virus passes from people to animals and back to people, it is called secondary spillover. This phenomenon can accelerate new variants establishing in humans that are more virulent and less responsive to vaccines. Secondary spillover of SARS-CoV-2 has already been reported among farmed mink in Denmark and the Netherlands, where it has led to at least one new SARS-CoV-2 variant.

Senior author and Cary Institute disease ecologist Barbara Han said, “Secondary spillover allows SARS-CoV-2 established in new hosts to transmit potentially more infectious strains to people. Identifying mammal species that are efficient at transmitting SARS-CoV-2 is an important step in guiding surveillance and preventing the virus from continually circulating between people and other animals, making disease control even more costly and difficult.”

Binding to ACE2 receptors is not always enough to facilitate SARS-CoV-2 viral replication, shedding and onward transmission. The team trained their models on a conservative binding strength threshold informed by published ACE2 amino acid sequences of vertebrates, analyzed using a software tool called HADDOCK (High Ambiguity Driven protein-protein DOCKing).

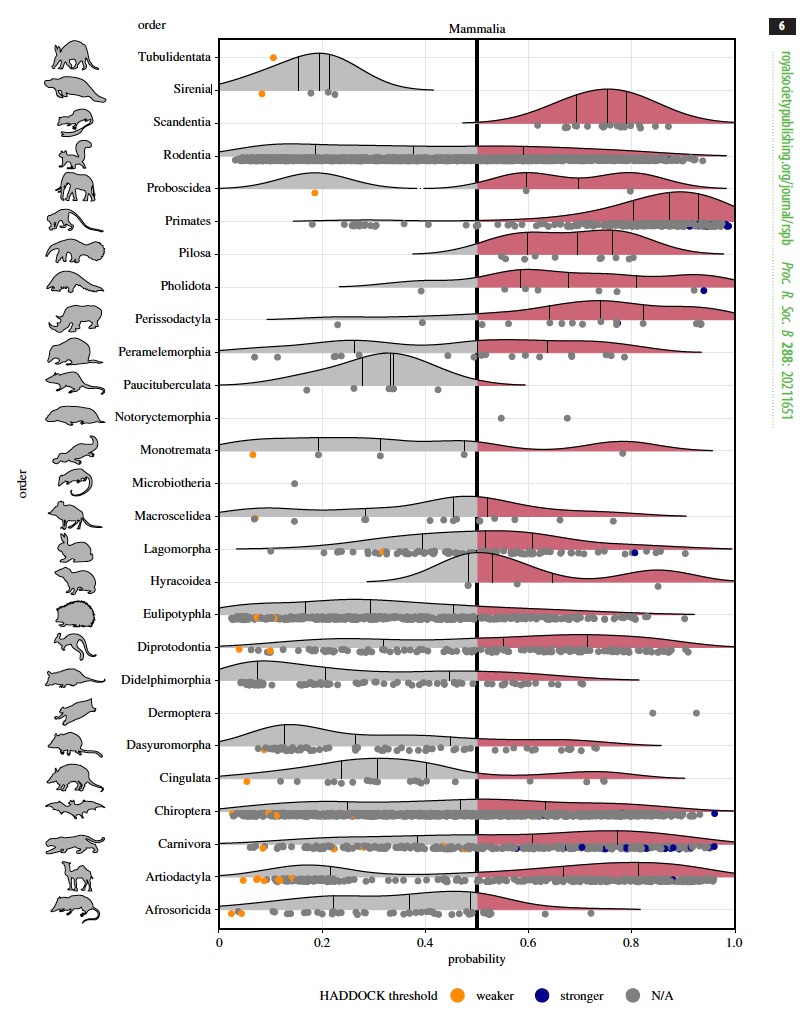

Ridgeline plots showing the distribution of predicted zoonotic capacity across mammals. Predicted probabilities for zoonotic capacity across the x-axis range from 0 (likely not susceptible) to 1 (zoonotic capacity predicted to be the same or greater than Felis catus), with the vertical line representing 0.5. The y-axis depicts all mammalian orders represented by the study's predictions. Points that were used to train the model are colored: Orange represents species with weaker predicted binding, and blue represents species with stronger predicted binding. Credit: Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

This software scored each species on predicted binding strength; stronger binding likely promotes successful infection and viral shedding.

Co-lead author and Cary Institute postdoctoral analyst Adrian Castellanos said, “The ACE2 receptor performs important functions and is common among vertebrates. It’s likely that it evolved in animals alongside other ecological and life history traits. By comparing biological traits of species known to have the ACE2 receptor with traits of other mammal species, we can make predictions about their capacity to transmit SARS-CoV-2.”

This combined modeling approach predicted zoonotic capacity of mammal species known to transmit with 72% accuracy and identified numerous additional mammal species with the potential to transmit SARS-CoV-2. Predictions matched observed results for white-tailed deer, mink, raccoon dogs, snow leopards and others. The model found that the riskiest mammal species were often those that live in disturbed landscapes and in close proximity to people – including domestic animals, livestock and animals that are traded and hunted.

The top 10% of high-risk species spanned 13 orders. Primates were predicted to have the highest zoonotic capacity and strongest viral binding among mammal groups. Water buffalo, bred for dairy and farming, had the highest risk among livestock. The model also predicted high zoonotic potential among live-traded mammals, including macaques, Asiatic black bears, jaguars and pangolins – highlighting the risks posed by live markets and wildlife trade.

SARS-CoV-2 also presents challenges for wildlife conservation. Infection has already been confirmed in Western lowland gorillas. For high-risk charismatic species like mountain gorillas, spillback infection could occur through ecotourism. Grizzly bears, polar bears and wolves, all in the 90th percentile for predicted zoonotic capacity, are frequently handled by biologists for research and management.

Han explained, “Our model is the only one that has been able to make risk predictions across nearly all mammal species. Every time we hear about a new species being found SARS-CoV-2 positive, we revisit our list and find they are ranked high. Snow leopards had a risk score around the 80th percentile. We now know they are one of the wildlife species that could die from COVID-19."

People working in close proximity with high-risk mammals should take extra precautions to prevent SARS-CoV-2 spread. This includes prioritizing vaccinations among veterinarians, zookeepers, livestock handlers and other people in regular contact with animals. Findings can also guide targeted vaccination strategies for at-risk mammals.

Han concluded, “We found that the riskiest mammal species are often the ones that live alongside us. Targeting these species for additional lab validation and field surveillance is critical. We should also explore underutilized data sources like natural history collections, to fill data gaps about animal and pathogen traits. More efficient iteration between computational predictions, lab analysis and animal surveillance will help us better understand what enables spillover, spillback and secondary transmission – insight that is needed to guide zoonotic pandemic response now and in the future.”

“Cross-disciplinary research like this is important to gain novel insights and is a collective learning endeavor for all involved, as each of us learns from the other field," Varsani said.

Varsani is also a researcher in the Center for Evolution and Medicine and the School of Life Sciences at ASU.

Authors were supported by various grants during the course of this work, including the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Story written by the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies with co-author Richard Harth of ASU.

More Science and technology

Advanced packaging the next big thing in semiconductors — and no, we're not talking about boxes

Microchips are hot. The tiny bits of silicon are integral to 21st-century life because they power the smartphones we rely on,…

Securing the wireless spectrum

The number of devices using wireless communications networks for telephone calls, texting, data and more has grown from 336…

New interactive game educates children on heat safety

Ask A Biologist, a long-running K–12 educational outreach effort by the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University, has…