When we think of climate, the stories we tell about the future are bad: megastorms, crop failures and heat waves loom over us, sending a signal that the problem is so vast, so complex, that it’s out of our control.

That narrative is compelling for some, but leaves others feeling hopeless, helpless and disillusioned. Even the most ardent champions of decarbonization sometimes focus more on sounding the alarm than imagining and mapping out what success might look like. Without positive climate futures — visions of climate adaptation and resilience that we can work toward — it’s much harder to motivate broad-based efforts for change in the present.

And those efforts for change are more urgent than ever, in the runup to the U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP26), a transnational summit in Glasgow, Scotland, that will bring together heads of state, climate experts and advocates to agree on coordinated global action to decarbonize our societies in the face of the escalating climate crisis.

The Climate Imagination Fellowship, hosted by the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University, seeks to inspire a wave of narratives about what positive climate futures might look like for communities around the world. The fellowship is supported by a grant from the ClimateWorks Foundation and is a partnership of the Center for Science and the Imagination, TED’s Countdown Initiative around the climate crisis and decarbonization and the United Nations High-Level Champions for Climate Action teams, led by Nigel Topping of the United Kingdom and Gonzalo Muñoz of Chile.

Today, the center is proud to announce four climate fellows: talented science fiction authors from all around the world who will create compelling visions of possible climate futures, grounded in real scientific, technological and social insights.

- Libia Brenda is a writer, editor and translator based in Mexico City. She writes speculative fiction as well as nonfiction and criticism about science fiction and fantastic literature. Her work has been translated from Spanish into English, Italian and Portuguese. She is one of the co-founders of the Cúmulo de Tesla collective, a multidisciplinary working group that promotes dialogue between the arts and sciences, with a special focus on science fiction; and Mexicona: Imagination and Future, a series of Spanish-language conversations about the future and speculative literature from Mexico and other planets. She was the first Mexican woman to be nominated for a Hugo Award for the bilingual and bicultural anthology "A Larger Reality/Una realidad más amplia." After that, she was so excited that she edited "A Timeline in Which We Don't Go Extinct," a bilingual anthology that is also a video game, which is free to download and play. She edited the Mexico special issue of the speculative fiction magazine "Strange Horizons," published in November 2020.

- Xia Jia is a speculative fiction author and associate professor of Chinese literature at Xi’an Jiaotong University in Xi’an, a city in the Shaanxi province in northwest China. Seven of her short stories have won the Galaxy Award, China’s most prestigious science fiction award. She has published a fantasy novel, "Odyssey of China Fantasy: On the Road" (2009), and four collections of science fiction stories: "The Demon-Enslaving Flask" (2012), "A Time Beyond Your Reach" (2017), "Xi’an City Is Falling Down" (2018), and "A Summer Beyond Your Reach" (2020), her first collection in English. Her stories have appeared in English translation in Nature and Clarkesworld magazine. Her nonfiction academic collection, "Coordinates of the Future: Discussions on Chinese Science Fiction in the Age of Globalization," was published in 2019. She is also involved in science fiction research, translation, screenwriting, editing and teaching creative writing and is currently working on a new science fiction book, titled "Chinese Encyclopedia."

- Hannah Onoguwe is a writer of fiction and nonfiction based in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State in southern Nigeria, a region famous for its oil industry. Her short stories have been published in the anthologies "Imagine Africa 500" (2016), from Pan African Publishers, and "Strange Lands Short Stories" (2020), from Flame Tree Press. Her work has appeared in publications including Adanna, The Drum Literary Magazine, Omenana, Brittle Paper, The Stockholm Review and Timeworn Literary Journal. In 2014, "Cupid’s Catapult," her collection of short stories, was one of 10 manuscripts chosen to kick off the Nigerian Writers Series, an imprint of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA). She won the ANA Poetry Competition in 2016 and was shortlisted for the Afritondo Short Story Prize in 2020. She holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Ibadan and a master’s degree in organizational psychology from the University of Jos. She works at a software company, providing support for the Nigeria Immigration Service.

- Vandana Singh is an author of speculative fiction, a professor of physics at Framingham State University and an interdisciplinary researcher on the climate crisis. She is the author of two short story collections, "The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet and Other Stories" (2014) and "Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories" (2018), the second of which was a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award. In 2014, she traveled to the Alaskan North Shore to create a case study on climate change for undergraduate education as part of a program award from the American Association of Colleges and Universities. Her work on a justice-centered, transdisciplinary conceptualization of the climate crisis is part of a forthcoming volume from UNESCO, "Charting an SDG 4.7 Roadmap for Radical, Transformative Change in the Midst of Climate Breakdown." Her short fiction has been widely published, including the short story “Widdam,” part of the interdisciplinary climate-themed collection "A Year Without a Winter" (2019). She was born and brought up in New Delhi and now lives near Boston.

Each fellow will write an original piece of short climate fiction, building on local opportunities, challenges, resources and complexities, and drawing on conversations with experts in a variety of fields, ranging from climate science to sociology to energy systems to biodiversity. They will also write a set of shorter “flash-fiction” pieces exploring a range of other possible futures shaped by the climate crisis and our collective responses to it. These pieces of short fiction will be collected, along with essays, interviews, art and interactive activities, in a "Climate Action Almanac," to be published in 2022.

In addition to crafting these works of climate fiction, the fellows will participate in a variety of public events, panels and workshops, including special programming at TED’s Countdown Summit in October 2021 in Edinburgh, Scotland, (where one of them will give a TED Talk), which will bring global leaders together to share a blueprint for a decarbonized future. Other events will be hosted in collaboration with partners including the British Library, Future Tense, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance, and the Hay Festival in Arequipa, Peru. At these events, the fellows will be in conversation with scientific experts, social science researchers, policy makers, early-career scholars, activists and other curious, insightful thinkers on climate action. They will also participate in co-creation activities with members of the public to imagine an even broader array of climate futures, building from unique local circumstances to global transformations.

“The goal of the Climate Imagination Fellowship, is to curate and share amazing new stories about what successful climate action might look like," said Ed Finn, the director of the Center for Science and the Imagination. "We need to envision positive futures to motivate large-scale change. We also want to invite people and communities around the world to imagine their own climate futures — to feel both agency, and a sense of responsibility, for defining a future that spurs us to take action today.”

“Authors of speculative fiction have shown over and over their capacity to envision possible futures, taking into account both the edges of science and technology as well as their social and human impacts,” said Bruno Giussani, TED’s global curator, who coordinates the TED Countdown program. “We are thrilled at the prospect of the four fellows and Kim Stanley Robinson bringing that perspective to the Countdown Summit conversation.”

The fellows are indeed joined by senior adviser Kim Stanley Robinson, author of the acclaimed climate fiction novels "Green Earth" and "New York 2140," and most recently, "The Ministry for the Future," which imagines a new transnational agency that advocates for the rights of future generations in the face of worldwide climate chaos.

The fellowship will generate hopeful stories about how collective action, aided by scientific insights, culturally responsive technologies, and revolutions in governance and labor, can help us make progress toward inclusive, sustainable futures. The visions of the future coming out of the project will focus on how we can create a vibrant, thriving global society that celebrates local variations and solutions, while achieving the international coordination and shared values we need to meet the challenges of the climate crisis.

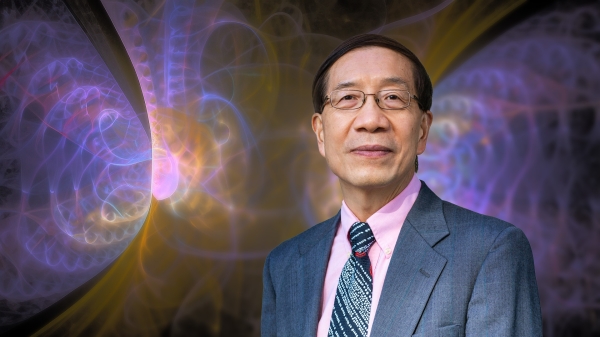

Top photo: The Climate Imagination Fellows will work with community members, researchers and policymakers to craft positive visions of climate futures. From left: Hannah Onoguwe, Xia Jia, Vandana Singh, Libia Brenda. Credits: Greatman Shots and Claudia Ruiz Gustafson.

More Science and technology

Extreme HGTV: Students to learn how to design habitats for living, working in space

Architecture students at Arizona State University already learn how to design spaces for many kinds of environments, and now they can tackle one of the biggest habitat challenges — space architecture…

Human brains teach AI new skills

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is rapidly advancing, but it hasn’t yet outpaced human intelligence. Our brains’ capacity for adaptability and imagination has allowed us to overcome challenges and…

Doctoral students cruise into roles as computer engineering innovators

Raha Moraffah is grateful for her experiences as a doctoral student in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University…