Biomaterials bolster the battle against cancer

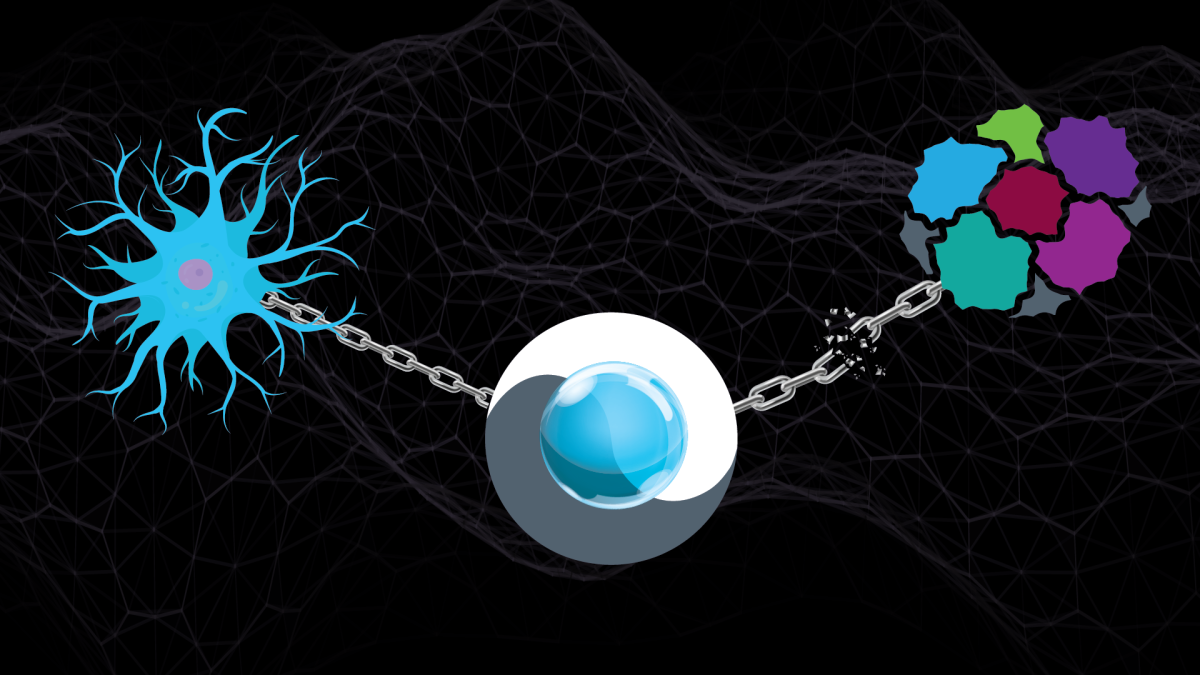

ASU Assistant Professor Abhinav Acharya is developing novel technologies that will permit the simultaneous use of cancer vaccines and chemotherapy treatments. Graphic by Rhonda Hitchcock-Mast/ASU

According to Abhinav Acharya, an assistant professor of chemical engineering at Arizona State University, “a single form of treatment is often not sufficient to defeat a given form of cancer."

"We need a combinatorial approach, meaning the use of two or more therapies together.”

For example, the tandem application of chemotherapy with immunotherapy or vaccine use could be much more effective than either measure alone. But the problem, Acharya said, is that each of these therapies is so taxing on the human immune system that they can’t be deployed simultaneously with a patient.

Solving this problem is the focus of a new project that Acharya is leading with the support of a grant from the National Institutes of Health. He is developing the first biomaterials-based technologies to modulate the functions of immune system cells in a way that can enable safe and effective combinations of clinical treatments to battle melanoma, ovarian cancer and potentially many other ailments.

Acharya works at the interface of materials science and immunology in the School for Engineering of Matter, Transport and Energy, one of the six Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU. His research for this NIH project focuses on cancer vaccines and applying the functions of their two major components: antigens and adjuvants.

Antigens trigger the immune system to create antibodies that attack a specific pathogen or toxin. These substances might take the form of inactive components from the targeted pathogen itself or, in the case of Acharya’s work, drugs tailored to induce a desired defense response.

Adjuvants are salt- or emulsion-based vaccine components that stimulate and amplify the immune system’s response to the particular pathogen targeted by the antigens. In other words, antigens identify the foe and adjuvants fuel the fight.

Part of Acharya’s work is developing novel adjuvants based on polymeric biomaterials generated from central carbon metabolites. The resulting polymers act as a source of cellular nutrients, and they can be fabricated either as microparticles or nanoparticles depending on their purpose.

“If the particles are micron-sized, they mimic the size of bacteria. If they are nanoparticles, they mimic the size of viruses,” Acharya said. “In either case, the immune system sees this foreign material as a threat and tries to digest it.”

This act of consumption is the key to delivering biomaterial-based nutrients to the body’s immune system when it is dampened during chemotherapy treatment. These nutrients can restore the chemo-suppressed metabolic pathways that enable sentinel-like dendritic cells to sound the alarm and prompt T-cells, a form of white blood cells, to fight the cancer.

Alongside rescuing the metabolic processes that help boost the body’s defenses, another goal is to disrupt the equivalent pathways that feed cancer cells. This latter task shapes three aims of this project, which specifically seeks to improve skin cancer treatment.

The first aim is to formulate and deliver a drug that disrupts a particular enzyme in the metabolic pathway of cancer cell glycolysis, which is the conversion of glucose into adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, a key fuel for cellular life. Halting this energy production pathway starves the cancer of the energy it needs to proliferate.

The second aim is similarly to formulate and deliver a drug targeting an enzyme in the metabolic pathway of cancer cell glutaminolysis, which is another means to generate ATP and other cancer-sustaining molecules within a tumor.

“And the third aim is to demonstrate that we can achieve these formulations at a scale to permit production for clinical use,” Acharya said.

Challenges to this work include generating a T-cell response that is robust enough to operate effectively in the context of both chemotherapy and the nutrient-deficient environment that the enzyme-targeting technology is creating in and around a tumor. But Acharya is confident of success after positive initial tests with cancerous human tissue in a laboratory setting.

Additionally, his interdisciplinary view of research already points to other applications for the innovations emerging from the NIH project.

“This is really a platform technology, so we can develop metabolic-modifying biomaterials for many purposes,” he said. “We are working right now with Dr. Marion Curtis, an immunologist with Mayo Clinic, to determine how to deploy this new technology against other types of cancers. As well, there may be new remedies for traumatic brain injuries and opportunities to better combat autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and so much more. The potential is very exciting.”

More Science and technology

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as…

Hacking satellites to fix our oceans and shoot for the stars

By Preesha KumarFrom memory foam mattresses to the camera and GPS navigation on our phones, technology that was developed for…