In the early 1970s, Steve Graham was a long-haired free-spirit hitchhiking across America, trying to find himself. All he needed to survive was a few bucks in his pocket, a jar of peanut butter and a loaf of bread.

Flash forward to 2021. The former hippie drifter is now a Regents Professor at Arizona State University.

Graham was recently named one of four Regents Professors for 2021. News of the elite designation, he said, came like a thunderbolt.

“Initially, I took the news rather matter of factly because it was such a surprise. I really didn’t see it coming,” said Graham, who is the Mary Emily Warner Professor of Education at ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “As my wifeGraham’s wife, Karen R. Harris, is also a Mary Emily Warner Professor of Education on the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College faculty. likes to say – who is also an academic – she could see that I was smiling a little bit more each day because the reality of it started to sink in. It’s nice to get recognition where you live.”

Regents Professor is the highest faculty honor and is conferred on full professors who have made remarkable achievements that have brought them national attention and international distinction.

Less than 3% of all ASU faculty carry the distinction.

“Steve exemplifies the importance of committing to research that matters. His life’s work has been about understanding how young people learn to write, and he has been a tireless advocate for the value of writing as a key to reading, learning and personal self-determination,” said Carole G. Basile, dean of the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at ASU. “His work illustrates what happens when education scholarship blends rigor and tenacity with compassion and empathy.”

For more than 40 years, Graham has studied how writing develops, how to teach it effectively and how it can be used to support reading and learning. In recent years he has been involved in the development and testing of digital tools for supporting writing and reading through a series of grants from the Institute of Educational Sciences and the Office of Special Education Programs in the U.S. Department of Education. His research involves developing writers and students with special needs in both elementary and secondary schools, with much of it occurring in classrooms in urban schools.

Graham has a particular interest in special needs students because he can relate to them.

“When I was younger and in my first four or five years of school, I was a kid who probably would have been labeled as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” said Graham, an Air Force brat who moved frequently. “I think from everybody’s point of view except for mine, those early school years were a disaster. The mantra from every teacher was, ‘Can’t sit still, can’t stay quiet, can’t keep his hands off others.’ When I later became a teacher, I decided to work with kids who had the same issues I had.”

Most of Graham’s learning issues were ironed out by a fifth grade teacher in Clovis, New Mexico, one of a dozen places his father was stationed throughout his military service. He said his teacher harnessed his excess energy with planned physical activities, constant movement and competitive problem solving. That year Graham moved from the bottom of his class academically to the top of it.

His newfound classroom success propelled his love of learning, which included a lot of reading. Being a Cold War kid, Graham had an affinity for science fiction. His father was an airplane mechanic, so the younger Graham was constantly surrounded by fighter jets and the latest technology, sparking his imagination. The first book Graham read, which he could not remember title of, was a Jules Verne knock-off about a group of people visiting Mars.

“When we were stationed in France, we had no television. My bedroom included two rooms of my own above a barn and nobody could monitor me because they lived in the main house,” Graham said. “I would stay up all night and read science fiction. Reading became an important part of my life.”

When Graham’s father retired in 1968, the family landed in Valdosta, Georgia. Graham attended Valdosta State College, where he majored in history and secondary education. After graduation, he wanted to taste life outside the Deep South. By then the counterculture of the 1960s had exploded, rejecting the cultural standards of their parents’ generation. White middle-class youth like Graham turned their attention to social issues such as the war in Vietnam, race relations, sexual mores, women’s rights, traditional modes of authority and a reimagining of the American Dream.

By then Graham no longer looked or acted like a military brat. He wore blue jeans and often went barefoot. He grew his hair to the middle of his back.

Steve Graham in the early 1970s.

He spent six months hitchhiking across America after he received his bachelor's degree in history and secondary education. He traipsed the county, visiting friends in New York and San Francisco, and showed up at the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami to stand alongside 3,000 other anti-war protesters. He held many odd jobs — most of them blue-collar — that did not satisfy his intellect or curiosity. He eventually drifted back to Valdosta, and academia.

“I had enjoyed student teaching a great deal as an undergraduate and I went into Valdosta State, introduced myself to this new assistant professor, Lamoine Miller, and said, ‘I’d like to work with kids,’” Graham said. “We talked and I was offered a job as his assistant. I look back in amazement because that day I had really long hair, wore a tank top, had holes in my jeans and had no shoes on.”

Graham cleaned up nicely, especially where it concerned research and evaluation. He received his master’s degree in learning disabilities and was encouraged by Miller to pursue his doctorate. It was a pivotal moment.

“I didn’t see myself as an academic until he (Miller) had suggested it to me,” Graham said. “When I went back into the classroom and started doing more research, participating in research, I had a completely different view of teaching. I realized I could really make a difference in the lives of students.”

Graham graduated from the University of Kansas in 1978 with a doctorate in special education.

After four decades in academia and a 138-page curriculum vitae filled with honors, awards and citations, Graham is no longer the pupil. Today he is a master teacher and researcher, a fellow in two prestigious education academies, and has authored/co-authored 14 books. Now with the Regents Professor designation, it could be a fitting end to a remarkable career.

That doesn’t seem likely, though. At age 70, Graham hikes two hours a day, is working on a pair of books, and has a hand in six research projects and grants.

“I’m not at start of my career. I’m not at the middle of my career, but I’m not ready to stop or slow down,” Graham said. “I love what I do so much. I can’t believe I get paid to do this.”

Top photo: Steve Graham, a Mary Emily Warner Professor of Education at ASU's Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, was recently named a Regents Professor. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU Enterprise Marketing Hub.

More Arts, humanities and education

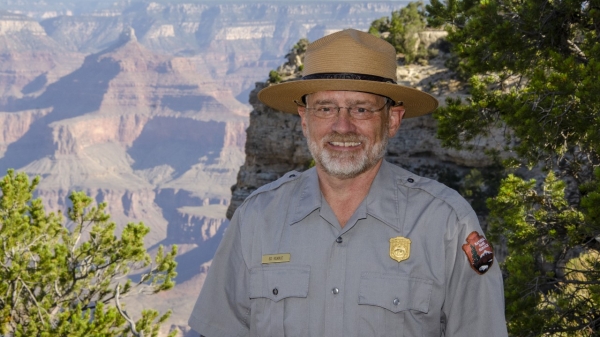

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…

Honoring innovative practices, impact in the field of American Indian studies

American Indian Studies at Arizona State University will host a panel event to celebrate the release of “From the Skin,” a collection over three years in the making centering stories, theories and…