Regents' Professor weaves tales of land, culture and community

Editor's Note: This professor profile is part of a series that looks at the achievements of seven outstanding faculty members who were named ASU Regents' Professors in 2011.

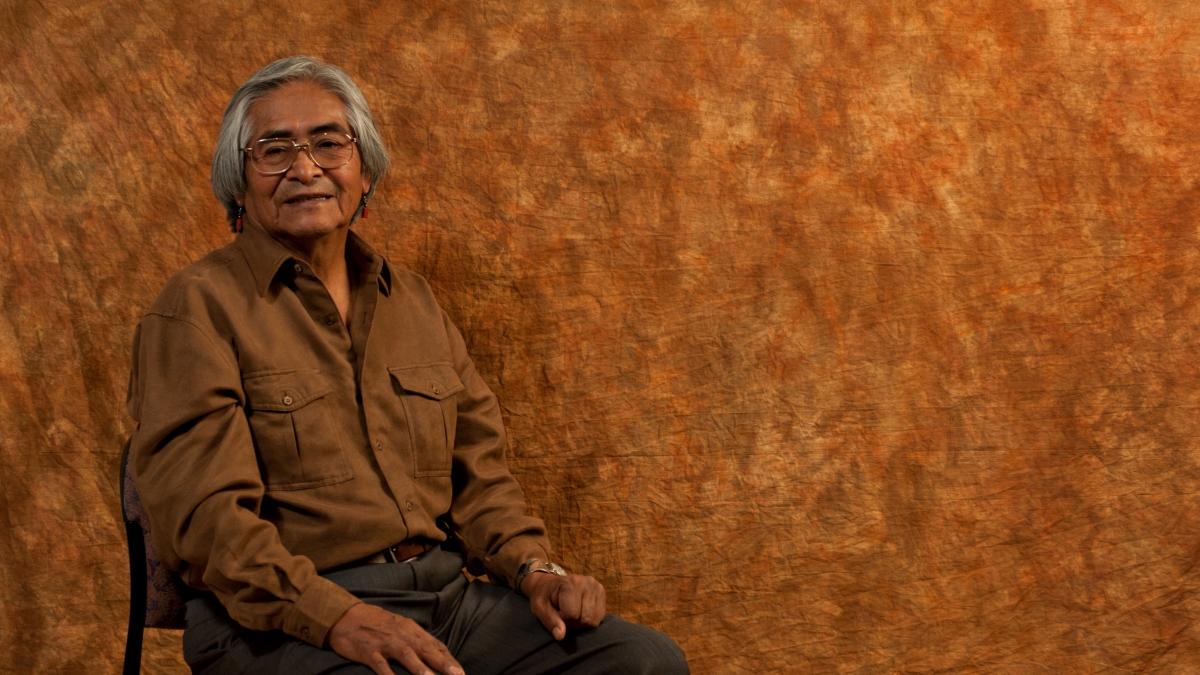

It’s a small class, and the students sit in a circle, with Simon J. Ortiz at the head. Ortiz is a striking figure, with his dark skin, turquoise and red-coral earrings, and longish graying hair.

He begins his informal lecture to the students taking his class, “Indigenous Rhetoric: Creative Struggle Concerning Indigenous Land, Culture, and Community.” He speaks first of the urban American Indian community of 100,000 or so in the Phoenix metro area; the surrounding tribes, such as Ak-Chin and Gila River; and the difficulties native youths face upon returning to the reservations. “Young people want to go home, but there are no jobs,” he says.

As Ortiz speaks, what seems at first like random thoughts tacked together begins to emerge as a story: a story the students in this classroom will help write during the semester. It will be their story, since all of the students are of the Indigenous peoples of Arizona – the story of how they relate to both the city-dwelling native peoples, and to the ones at home on their tribal lands.

The students perhaps don’t realize what a privilege they have, sitting in a small class with Ortiz, who has just been named a Regents’ Professor. But they become aware when a visitor tells them the news.

That Ortiz weaves tales of land, culture and community in his class is no surprise. Ortiz is a renowned poet, scriptwriter, storyteller, author and essayist in the ASU Department of English.

He was among the first to be published in the Native American literary renaissance of the 1960s, along with such icons as Leslie Marmon Silko, N. Scott Momaday, Joy Harjo, Laura Tohe and Lawrence Evers.

His was a circuitous path to the university classroom. He was born in the early 1940s at the Indian Hospital in Albuquerque and raised on the Acoma Pueblo reservation in New Mexico. Following high school he worked in the uranium mines and processing plants of the Grants Ambrosia Lake area.

After working a year at the mines, he quit and went to college to study chemistry – although he was also interested in writing at the time. But college, at the time, was not a good fit, so he enlisted in the Army “to see new places and meet people.”

After the Army, Ortiz returned to college and began writing again, having his first poems and stories published in small literary journals. But again, college didn’t seem to work out, so Ortiz dropped out again and began publishing small newspapers.

In the 1970s, Ortiz began a new battle, one familiar to his family: alcoholism.

“I knew the harm as a child, he said. “I grew up in a dysfunctional family and felt belittled in school. Alcohol subdues your feelings. And, my father was an alcoholic.” Ortiz is celebrating his 18th year of sobriety – “a major accomplishment,” he says.

That Ortiz has written so many books – in English – is amazing, considering his heritage as a native speaker and his distrust of the English language.

Ortiz said, in “A Circle of Nations: Voices and Visions of American Indians,” that he “wasn’t really sure that writing stories and poems was the best way to express myself as an Indian. I felt that expressing myself in the ‘Mericano’ language –English – was a modern-day trait that worked against me as an Indian, against all of us as Indians. Like most Indians of that time, I didn’t trust the Mericano language, because it had been used so often to hurt us.

“English was the language of the dominant culture, of government, of treaties, of Indian schools where children were taught that there was something wrong with being Indian. Although I couldn’t articulate it then, I had begun to realize that only when we had gained a stronger sense of our Indian selves would we be able to use English to express ourselves for who we are.

“By comparison, the language of my childhood, the ancestral language of the Acoma Pueblo People – Aaquumeh hano – is imbued with a sacred and mythic power that embraces everything of spiritual and human importance. Our culture, our identity, is conveyed by language, by the oral tradition. It carried the knowledge of creation and existence. It is the way we perceive and express the meaning of our lives, the way we know ourselves as a strong and enduring people. And for this reason, it is sacred.”

His nomination for the title of Regents’ Professor; his noted 24 books, including “Going for the Rain” and “From Sand Creek;” his work with public school curriculum design; his organization of the Simon Ortiz-Labriola Center Indigenous Speaker Series; his mentorship of students; and his community participation all have had “a significant positive impact on native and non-native communities.”

The students in “Indigenous Rhetoric: Creative Struggle Concerning Indigenous Land, Culture and Community” will doubtless feel that impact as they write their own stories, and the stories of those Indigenous peoples who surround them.