In workplaces across America, a new noise has become part of the familiar office soundscape: the whir of an electric motor that announces a co-worker’s rise from their chair to a standing position.

Yet, while sit-to-stand workstations are being installed in offices at a rapid clip, those who can boast having one at their disposal are still in the minority, often because of cost or workplace policies. And although the health risks associated with a sedentary lifestyle are becoming more widely accepted, some argue that simply encouraging employees to move more throughout the workday is enough to make a difference.

Others disagree.

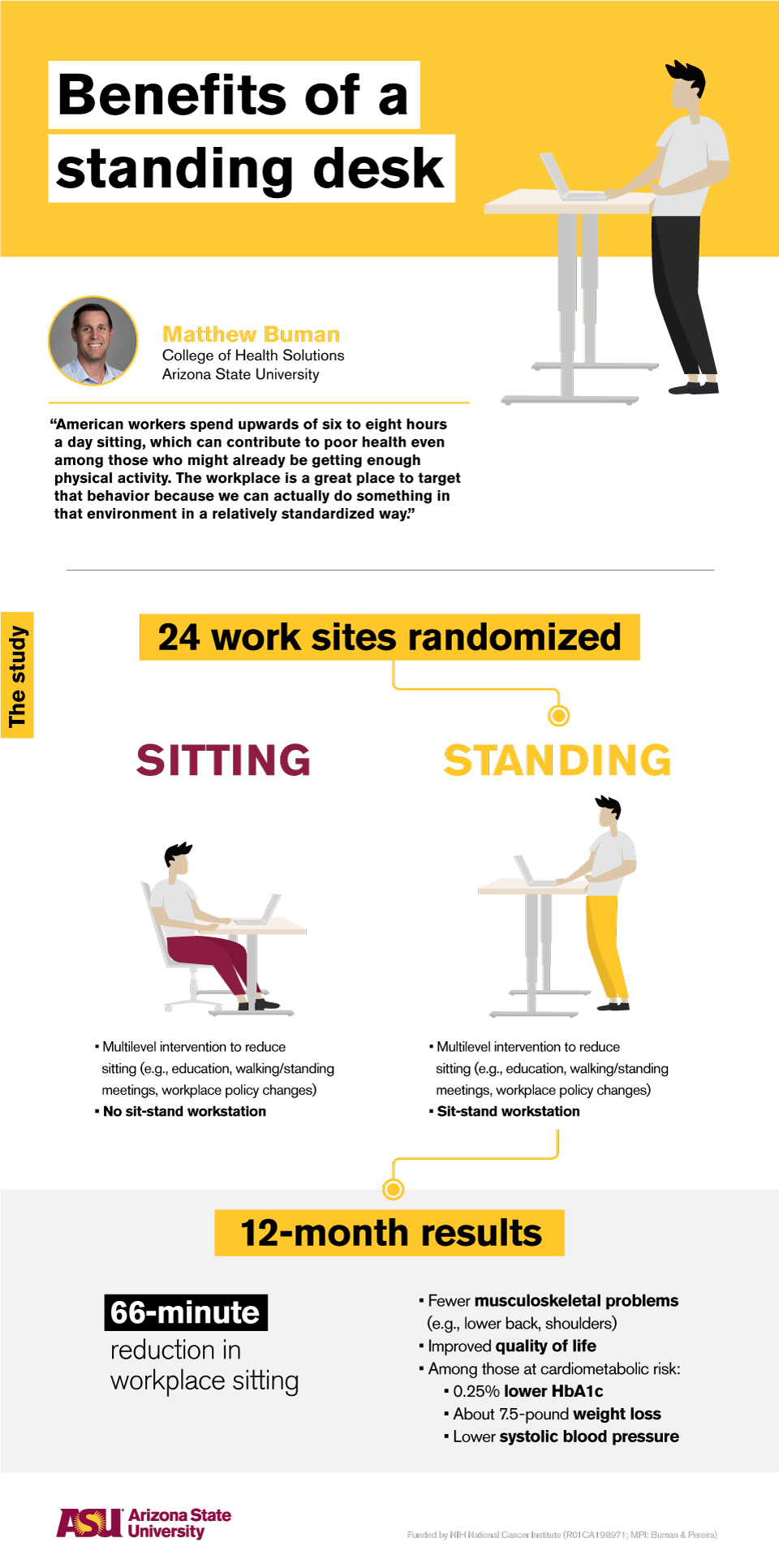

“American workers spend upwards of six to eight hours a day sitting, which can contribute to poor health even among those who might already be getting enough physical activity,” said ASU College of Health Solutions Associate Professor Matt Buman. “The workplace is a great place to target that behavior because we can actually do something in that environment in a relatively standardized way.”

In a study funded by the National Institutes of Health, Buman and colleagues at the University of Minnesota sought to determine whether providing employees with sit-to-stand workstations and programming that encouraged integrating more movement into the workday would be as effective or more effective than just the programming alone.

The results, which found that workers who received the sit-to-stand workstations sat less and showed improvements in health and quality of life compared with those who received only “move more” programming, were published in a paper by the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.

In a large cluster trial, Buman and colleagues selected 24 work sites in two states — half in Arizona and half in Minnesota — where sitting during the day was common and randomized them to receive one of two interventions for a 12-month period.

Half received supportive programming that ranged from emails from supervisors geared toward stimulating employee motivation to enacting policy-level changes regarding acceptable footwear. And the other half received both supportive programming and a sit-to-stand workstation.

Researchers found that participants who received both supportive programming and a sit-to-stand workstation — referred to as the “stand-plus” group — sat about one hour less per eight-hour workday than those who received only supportive programming. The former group also showed reductions in musculoskeletal issues and reported improved quality of life.

As a bonus, researchers were pleased to see participants in the stand-plus group show reductions in weight.

“That was surprising,” Buman said. “We never hypothesized that they may lose weight, but we’re seeing some initial indications that that may be due to reductions in appetite and energy intake. It could be that they were eating less because they were standing more.”

And among the nearly 100 prediabetic participants, researchers found clinically meaningful improvements in cardiometabolic rates, including reductions in fasting glucose and blood pressure.

Participants were evaluated at the beginning of the study, at three months and at 12 months. All of the beneficial changes they experienced began at three months and were maintained at the 12-month mark. Initial evaluations of participants after 24 months also reflect maintained benefits.

“What we typically see in physical activity studies is that we can initiate change but we can’t maintain it,” Buman said. “So this is really exciting because we’re showing that we can actually sustain change. A lot of that has to do with part of the intervention being a physical change in their environment. It becomes sort of an easy option to stand because the desk itself is there and present all the time.”

Infographic by Alex Cabrera/ASU Now

But Buman and his team acknowledged that getting participants to actually use the sit-to-stand workstation might require some changes to workplace culture.

“We tried to address certain cultural beliefs in our study,” Buman said. “We required every work site to have a work site leader who, among other things, was required to write an email at the beginning of the program and quarterly throughout the year inviting employees to participate. Basically saying, ‘At our workplace, we stand for health and we want you to take charge of your health because it’s important to us.’ People want to be healthier, but they don’t want to do it at the cost of their job.”

The researchers also noted that even though stand-plus participants increased the amount of standing they did at work, they did not compensate by sitting more after work, nor did their amount of physical activity in general increase.

“I view this as intervention that doesn’t compete at all with an exercise program because it’s an additive thing,” Buman said.

In 2018, Buman served as one of nine special consultants for a report that informed an updated version of the national Physical Activity Guidelines, first published in 2008 to inform public health policies.

The most recent iteration of the guidelines reflect the latest, most accurate scientific evidence regarding physical activity. One of the key updates is a greater recognition of sedentary behavior, defined as sitting, with the new recommendation calling for the usual 150 minutes of moderate activity per week in addition to sitting less and moving more in general.

And while Buman agrees with the recommendation regarding physical activity, what this study suggests is that just standing more can also result in benefits to your health.

“We didn’t get anybody to move more,” Buman said. “We just got them to stand more,” and they still saw health benefits.

But he also stressed the importance of balance.

“The caveat is too much standing is also probably not good for us, as that could create other musculoskeletal issues,” Buman said. “So people who are on their feet all day long — people working in a steel mill, or nurses or teachers — maybe they need to think about sitting more. The next position is the best position. If you’ve been sitting for awhile, maybe you should stand. If you’ve been standing awhile, maybe you should sit.”

Buman and colleagues have now begun a new project to test the programming nationwide for best practices for workplaces to implement it.

“Sit-to-stand workstations are being adopted widely across the country,” he said. “They’re no longer just for those who have a doctor’s note. People are asking for these and expecting them in their workplace. It used to be a cost barrier, but they’ve come down in price. Now the problem is that even though many workplaces provide them, they don’t provide support. So we’ll be testing delivery mechanisms to find the smartest way to scale up the program and retain health benefits.”

Top photo: ASU College of Health Solutions Associate Professor Matt Buman uses a sit-to-stand workstation every day. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Health and medicine

From lab to startup: ASU researchers drive health innovation

By Emmanuelle ComptonThe future of engineering-driven health innovation is currently unfolding at Arizona State University.In the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, part of the Ira…

Creepy-crawly science that matters

Written by Douglas C. TowneWhen Karen Clark was a child traveling with her grandfather, the late ASU Professor Herbert L. Stahnke, she didn’t realize how unusual their evening routines were.“When we…

A new heart

Written by Daniel Oberhaus, ’15 BAEach year, around 1.3 million children are born with congenital heart disorders, malformations that can include missing chambers or misplaced vessels. It’s the most…