Reaching for meaningful mind-body connections

Sydney Schaefer, an Arizona State University assistant professor of biomedical engineering, conducts research on the aging brain and its connection to physical rehabilitative practices in the Motor Rehabilitation and Learning Lab. Schaefer and her research team recently developed a new functional reaching task that can better indicate cognitive ability in older adults and can even predict future decline. Photo by Erika Gronek/ASU

Just as our brains develop as we grow up, they can also decline as we age. Understanding how older adults’ brains change is important to help improve quality of life and advance interventions for people dealing with dementia.

Along with measuring memory, processing speed and attention, scientists can also use physical strength and activity tests to reveal more about the inner workings of an aging brain.

“Physical assessments may offer additional insight into brain function that cognitive assessments only partially reveal, so long as the physical assessment is designed accordingly,” said Sydney Schaefer, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University.

For example, arm and hand coordination is sensitive to cognitive aging, so observing a decrease in that coordination could indicate an oncoming decrease in cognitive function. However, incorrectly designed physical assessments could decrease confidence in these methods to identify dementia or Alzheimer’s disease risk, especially in early stages.

Questioning what we think we know

The existing literature of observational studies reports a statistically significant association between cognitive assessment performance and how firmly an older adult can physically grasp things, or their grip strength. There’s even a catchy phrase for it: “People who grip better, think better.”

Grip strength tests are conducted using a dynamometer, a device that converts the hand’s muscular strength into a measurement of force.

People with lower grip strength, after accounting for sex-based strength differences, tend to have lower cognitive assessment scores. But Schaefer says there’s a catch.

“This relationship ‘paved the way’ for the working hypothesis that motor and cognitive processes share functional and structural brain networks, and suggests that studying these collectively can give us insights into overall brain health,” Schaefer said. “However, our analyses in our recent paper in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry show that even though the relationship is statistically significant, it is not necessarily functionally or clinically meaningful.”

Schaefer’s research team, including Andrew Hooyman, a biomedical engineering postdoctoral scholar, and others outside of ASU, analyzed publicly available open-source data sets to really put grip strength’s vigor to the test.

They found that the full range of possible grip strength scores would predict only a very narrow range of possible cognitive scores.

Hooyman was surprised at grip strength’s lack of clinical meaningfulness to predict cognitive abilities.

“Prior to our paper, there have been close to 20 different peer-reviewed articles reporting the significance of grip strength to predict cognition,” said Hooyman, who performed data analysis and simulations. “The primary aim of this paper is to demonstrate that although grip strength has been shown to be statistically significant, the overall relationship may not be meaningful, and as researchers we need to be mindful of that distinction.”

Schaefer and her team also conducted a more rigorous data analysis than previous studies conducted to investigate grip strength's association with cognition. Along with the data science approach to looking at the open-source data, the team’s multimodal approach included data simulations in the statistical programming language R and their own experimental data.

“Usually, most studies only use one or maybe two of these approaches at best,” Schaefer said. “The advantage of this multimodal approach is that it better evaluates the rigor and reproducibility of the findings and minimizes the likelihood that our results are spurious or unreplicable — in other words, not a fluke.”

Schaefer hadn’t previously worked on a project with this amount of data simulation, but having Hooyman on the team was instrumental to their success.

“Dr. Hooyman’s expertise has really allowed us to increase the rigor of our analyses to include more multimodal approaches like simulations,” Schaefer said. “He has really added a lot of new directions to our lab.”

Developing a new solution for real-world applications

Part of their findings in Schaefer’s Motor Rehabilitation and Learning Lab included developing a new method to assess cognition called a functional reaching task, which Schaefer says is “as simple and easy to administer as grip strength, costs less and has a stronger relationship with cognition.”

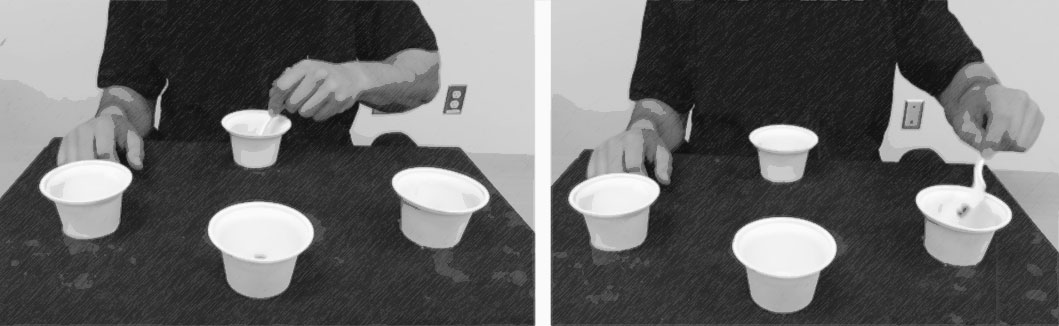

The functional reaching task developed by Schaefer’s lab involves a person using a spoon to scoop raw beans from one small cup to one of three target cups arranged in a semicircle around the starting cup. The person is timed using a simple stopwatch to see how long it takes to scoop and distribute 30 beans, two at a time, evenly among the three target cups.

A depiction of the functional reaching task developed by Sydney Schaefer’s Motor Rehabilitation and Learning Lab. The participant scoops up raw beans with a spoon and moves them to one of three target cups. This image is adapted from “Dexterity and Reaching Motor Tasks” by Motor Rehabilitation and Learning Laboratory, which is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“There’s nothing fancy about what we’re doing, which makes it incredibly scalable,” Schaefer said, noting it does not exhibit sex-based differences or involve wearable sensors or video capture technology as is the case in other assessments.

These are key features that make this assessment implementable now at a low cost and with minimal training. Schaefer and her team have begun testing how well people can administer this assessment on themselves at home, which means making it user-friendly is imperative.

Studying the motor behavior of reaching isn’t new, Schaefer said. It’s been around for nearly a century to help scientists understand how the brain controls movement, but not in such a functional way that reflects how humans move in daily life.

“The overwhelming majority of studies utilize a very constrained version of reaching in which the person is allowed to reach in only two dimensions, such as along a tabletop without lifting their arm off of it, and without having to grasp or manipulate objects,” Schaefer said.

While a two-dimensional reaching test can say a lot about neural control of limb movements, Schaefer said it doesn’t translate well to day-to-day life.

“So we have spent the last few years adapting this well-oiled paradigm into something that better reflects functional movement, and by doing so within older adult cohorts, we have stumbled upon its value in studying cognitive-motor interactions and aging.”

Encouraging scientists to consider a new approach

Schaefer’s team is validating this proof-of-concept assessment, but so far it has shown robust correlation to the three main cognition categories used by scientists: cognitively intact, mild cognitive impairment and early dementia.

It’s also a good example of why scientists should challenge themselves to consider whether the statistical significance of grip strength is also meaningful in clinical and real-world settings, and to incorporate multimodal and data science approaches to improve scientific rigor and reproducibility. It was the fact that Schaefer’s research team couldn’t replicate previous grip strength findings but they could replicate functional reaching results that sparked their analysis.

More importantly, functional reaching tasks show the ability to predict which adults will decline over time, whereas grip strength cannot do so. These findings were published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

“Measuring grip strength at a single point in time really hasn’t shown this prognostic ability, whereas our task has,” Schaefer said. “Thus, it appears that our task has value in providing a ‘sneak peek’ into a person’s future cognitive or functional state.”

Working with a multidisciplinary team helped Schaefer’s team determine the functional reaching task’s translatability outside the lab.

Michael Malek-Ahmadi, a Banner Alzheimer’s Institute biostatistician, helped Schaefer and Hooyman by lending his expertise in working with large data sets and his knowledge about cognitive assessment based on his training in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Elizabeth Fauth, an associate professor at Utah State University and longtime collaborator with Schaefer’s lab, contributed expertise on gerontology (the study of old age) and population data and assisted the team in data analysis and interpretation.

“(Fauth’s) work focuses on declines in activities of daily living in older adults, which really helped us tackle the ‘so what?’ of our findings,” Schaefer said.

Schaefer’s team will continue to look at what the functional reaching task can tell the scientific community about aging brains and what mind-body connections are at play. Data science approaches like the ones she and her team are using are particularly timely during the pandemic when in-person data collection is severely limited.

“The clear relationship between our motor task and cognition opens the door to a number of other questions within rehabilitation, such as whether cognitive impairment interferes with motor rehabilitation, or whether cognitive training enhances motor function,” Schaefer said. “These are very relevant clinical questions, since it is well known that both cognitive and motor function decline with advancing age.”

More Science and technology

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would…

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to…