If you’ve ever spent a winter in Maine or Minnesota, you know you need special clothing — parkas, mittens, long johns — to survive. If it’s cold enough outside, a human can die in less than an hour, depending on conditions and the type of exposure.

On the flip side of that coin, unprotected and exposed humans can die in three to six hours in the dead of summer in the desert Southwest. But there really isn’t any clothing designed for that extreme. You either take a lot off and hunker down in the shade or wear loose-fitting shirts and pants.

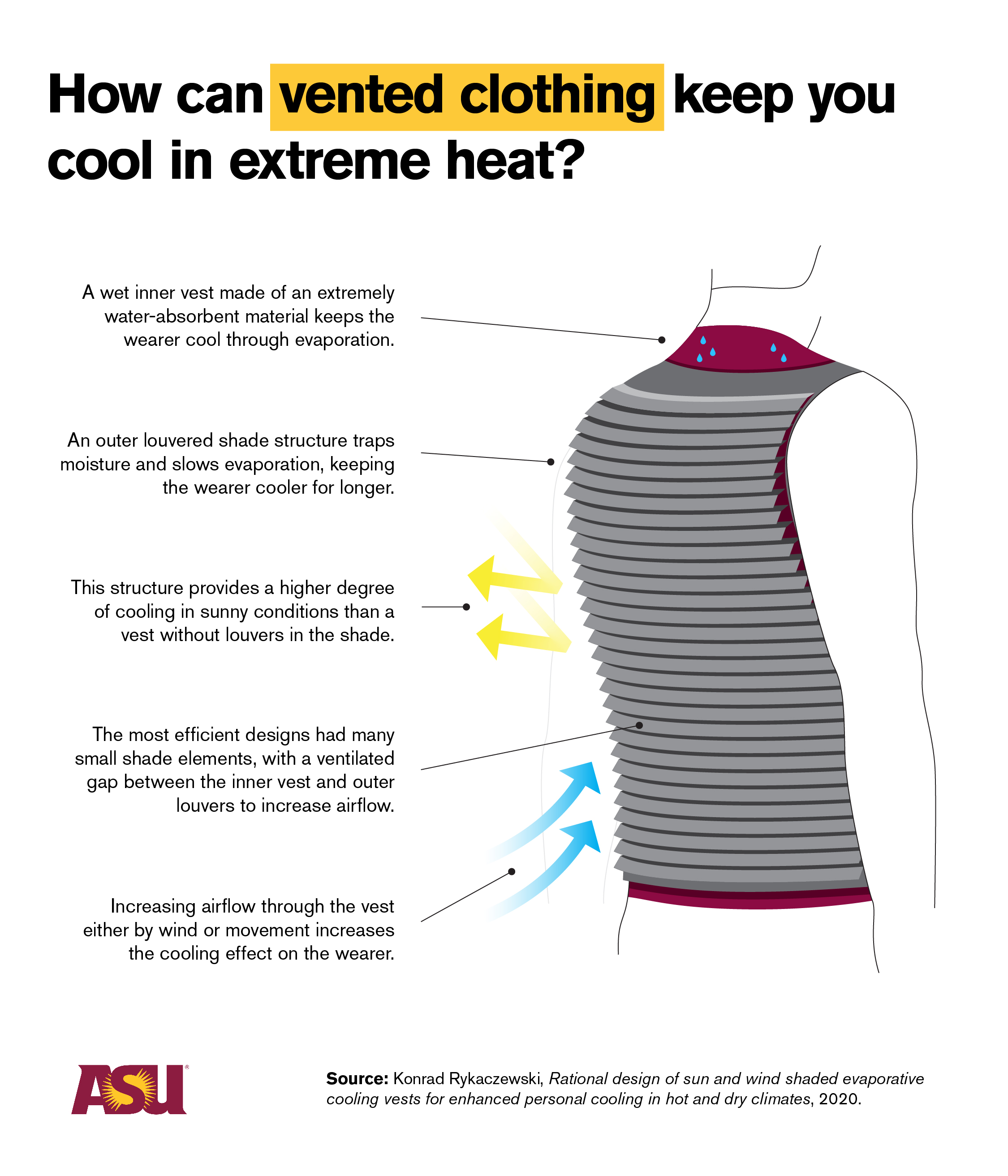

Now, Arizona State University engineer Konrad Rykaczewski has created a design for a cooling vest to keep wearers comfortable in scorching conditions. His paper on the design was published this month.

A third of the world’s population lives in areas that will be as hot as the hottest parts of the Sahara within 50 years, according to a recent study. Phoenix is getting hotter, at least at night. The average number of hot days has gone up a little bit, but lows have rocketed in the past four decades.

“This is substantial, and this is real,” said Rykaczewski, an assistant professor at the School for the Engineering of Matter, Transport and Energy at ASU.

Rykaczewski is a thermal dynamics engineer who is working on various designs and materials to wear in hot temperatures. “Cool future fashion,” he calls it.

A mountain biker and father, he hits the trails at 4:30 a.m. on summer mornings.

“Sometimes that’s not enough,” he said. “It’s becoming challenging. … Anything over a daily low of 95, it’s going to be impossible to do anything outside. When the sun is up, it’s going to heat up even more quickly.”

By the time his kids wake up, it’s already 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The only things he can do with them involve the sprinkler or the swimming pool.

That inspired his latest idea. Through evaporation, it’s possible to be really cold in the dead of summer. Climb out of the pool in full sun on a July afternoon and a chill will sweep your body. While it may be as hot as a preheated oven, Arizona is blessed with low humidity — making evaporative cooling a good option.

There are cooling vests on the market, but they need to be soaked and resoaked while worn. They’re made of super-absorbing polymers — diaper material — which can absorb 100 times their own mass of water.

The problem is evaporation at the surface of material. The water just flies away.

“You can think of having this hydrated swollen polymer with water against your skin,” Rykaczewski said. “At the surface of the vest you have evaporation. You have some heat that goes into it from the body.”

On the outside, you have Phoenix summer heat. The vest is cooler than the outside. Materials have to reflect solar radiation and infrared.

Rykaczewski quantified it in terms of heat flux: the amount of heat you can pull out per unit area. On an average human, that’s 1.8 to 2 square meters of surface area.

He plotted heat flux — body cooling and body heating — for standing in the shade and in the sun.

“If you are in sunny conditions and there’s not much air movement, you’re evaporating a fair amount of water, but you’re getting heated,” he said.

You end up getting heated in the sun even though you’re wearing an evaporative vest. Because of the sun, you’re getting double the heat you’re producing with your body. You need to get a fair amount of breeze going over you to feel any cooling effects (and you’re still losing water.)

“You’re getting less heated than you would be without the vest, but it defeats the purpose,” he said. Eighty to 90% of the water you are wearing is wasted. If you “wear” a pound of water, only (roughly) 10% is cooling you.

So, too much convection is bad and too much exposure is bad.

“The obvious answer is you need to wear some kind of a shade over that,” Rykaczewski said. “The crazy people who wear aluminum hats so aliens and the government doesn’t listen in on them? That’s actually the way to go. It’s better than a white T-shirt.”

There are products with metallized low-polymer forms, such as space blankets. In Phoenix, these would be useful to cool you because you’re not losing any heat to the environment.

Rykaczewski’s solution combines the two conceptd: an evaporative vest on the bottom and a foil vest on top to thwart radiation. “But still you obviously need a little bit of air flow and access in order to have the evaporation actually happen,” he said.

In order to maximize the amount of heat being removed, you need a gap between the surface of the vest and the shade.

“Of all the simulations I did, that was the most important,” he said. “You need that gap.”

But the gap can’t be too big, otherwise you lose moisture, especially if it’s windy. Rykaczewski thought of louvers. “You reduce the amount of water that evaporates from it, and waste,” he said.

“The whole point is to get most of the water in the vest to cooling you. …The point is for it to last an hour, hour and a half, so you can get something done outside and be reasonably comfortable.”

The design is not intended for running a marathon in August. He envisions it for going for a walk, doing yard work or playing with the kids.

Rykaczewski plans on a few more years of testing and making mockups before venturing into the commercial realm.

Graphic by Alex Davis/Media Relations and Strategic Communications. Top photo courtesy Pexels

More Science and technology

Largest genetic chimpanzee study unveils how they’ve adapted to multiple habitats and disease

Chimpanzees are humans' closest living relatives, sharing about 98% of our DNA. Because of this, scientists can learn more about human evolution by studying how chimpanzees adapt to different…

Beyond the 'Dragon Arc': Unveiling a treasure trove of hidden stars

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has set a new milestone: capturing images of over 40 individual stars in a galaxy so distant that its light has traveled since the universe was only half its…

ASU selected as home and partner for CHIPS and Science Act-funded national facility for semiconductor advanced packaging

Following a week where a spirited effort by the Sun Devil football team captured the nation’s attention in the Peach Bowl, it is Arizona State University’s capability as a top-tier research…