America needs to cultivate a culture of service to solve problems

The current COVID-19 pandemic highlights the critical need for the United States to develop a strong system for young people to engage in public service — much like the Public Service Academy at Arizona State University.

That was a recurring theme of several experts who participated in a virtual panel discussion Tuesday titled “Meeting the Moment: The Next Generation of Service.” The event was sponsored by ASU, the McCain Institute for International Leadership and the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service.

The McCain Institute was founded at ASU in 2012, said Ben Freakley, a professor of practice at ASU and a senior adviser to the institute.

“In some respects, it’s come full circle to now in this moment, with this pandemic causing us to reflect on our future and the significance of service,” said Freakley, who retired from the U.S. Army after 36 years and is a special adviser to ASU President Michael Crow.

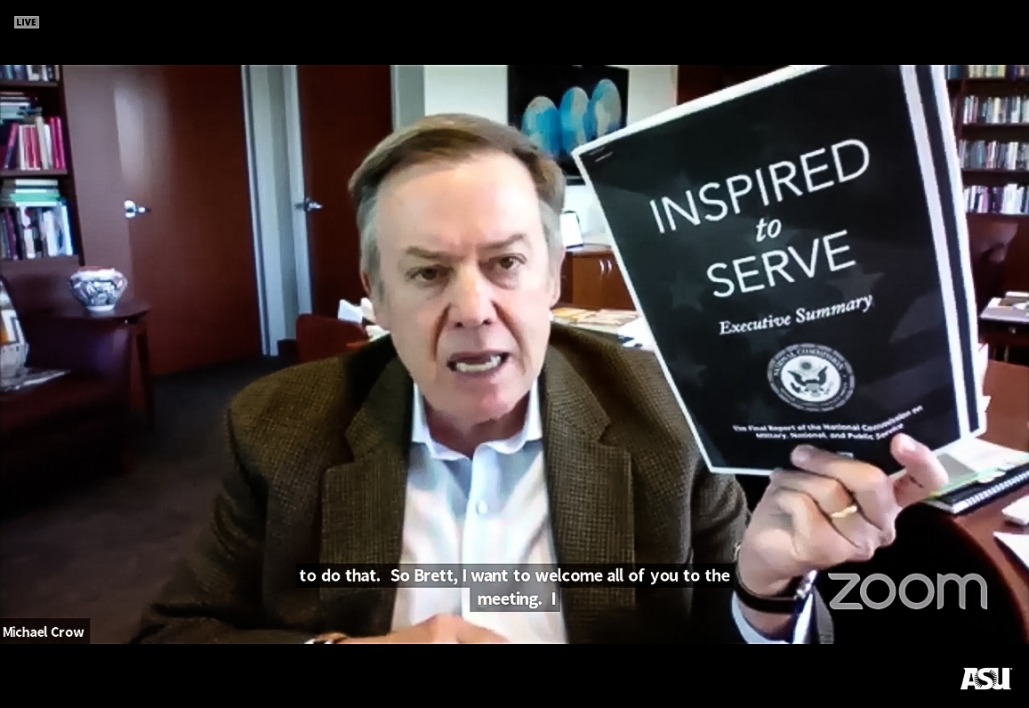

After 2½ years of public hearings and research, the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service released a major report called "Inspired to Serve" last month with recommendations on how to create a culture of service in the U.S. Among the report’s recommendations were: revitalize civic education; create a platform to help Americans discover service opportunities; increase the value and flexibility of incentives for national service programs like AmeriCorps and Senior Corps; establish new models for national service, such as fellowships to support a service year at a nonprofit organization in rural and underserved areas; reform hiring for federal jobs and expand selective service registration for military service to include females.

Crow said that Americans need to embrace the concept that service to the country extends beyond the military.

“Serving our country is not just the defense of our nation, which is necessary but insufficient by itself,” he said. “It’s preparing the people of the country for any eventuality.”

Crow said that the spirit of public service is less focused than it was 80 years ago, during the Greatest Generation, and that reading the Preamble to the Constitution is one way to become motivated.

“‘And promote the general welfare’ is forgotten by many people. It’s the success of the society itself, and you do that by service to the society, not just your individual welfare,” Crow said.

“To me, the argument for national service is the focus on how we will ultimately attain the highest order of outcomes as mandated by the Preamble to the Constitution.”

Crow helped to create the Public Service Academy at ASU, which was the first undergraduate program in the nation to create a collaborative military and civilian service experience when it debuted in fall 2015.

Among the topics discussed at the Tuesday event were:

Creating a culture of service

Steven Barney, former general counsel to the Senate Armed Service Committee and a member of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service: What we’re looking to do is to create the opportunity to build this culture of service. People can’t just stumble into it. That means starting with the youngest Americans and exposing them to leadership opportunities through service. Our vision is that when an individual arrives at their senior year of high school and you ask them, "What is your plan to serve?" they don’t shrug their shoulders.

State Rep. Aaron Lieberman, a Democrat who represents north Phoenix: It happens both informally and formally. Informally, lessons happen in our homes from parents. We see this in our faith communities. But there’s a role for government too. I love the idea of looking at more combined efforts between the military and national service. We see our biggest threats aren’t ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) pointed at us. It’s more varied and might not be military-based.

Think of service careers beyond the military

Lieberman: This is hugely important because one of the key challenges is if we rely only on people who can afford to volunteer, there will be limitations. So there needs to be that opportunity to receive compensation. We just authorized $2 trillion in spending (on the COVID-19 crisis) and to my knowledge, none of it is going toward "How can we get Americans to help with this response?" It would be great if the next COVID-19 package could get Americans on the front lines.

Barney: It’s awareness, aspiration and access. We met with a group of high school students, and part of the discussion was, "Has anyone talked to you about service?" And it was crickets. The idea of going into service was not presented to them. Aspiration is, "How do I use my skills in service that would help the nation as well as be a benefit to me?" And the final point is access. When I was in New Hampshire, I met a woman working with opioid addicts to make sure they were not forgotten. I asked how she became involved, and she said, "I’m a recovering addict, and until this opportunity I did not have a path forward." And when an individual goes into that strip mall recruitment center and learns that there is some aspect in their background that makes them not qualified for military service, there needs to be a warm handoff of that individual who has a heart to serve.

Should national service be mandatory?

Barney: As we talked to people, we came down on the position that the better thing for our nation is to capitalize on the sense of volunteerism that is part of the American spirit. When we said "mandatory" you could feel the walls go up. In their hearts, people do want to serve and if we can build this culture of service, people will have more opportunities.

Inspirations to serve

Sami Mooney, recent ASU graduate who was a member of the ASU Next Generation Service Corps and who now teaches fourth-graders in Teach for America: I grew up in a family that valued public service in different ways. My dad is a small-business owner, and my mother is a special education paraprofessional. I grew up with that philosophy of helping out. In the Public Service Academy and all of those experiences, it was narrowing the lines of my skill set and what social mission was closest to my heart.

Avril Haines, former principal deputy national security adviser and a member of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service: My dad was a science teacher, and one of the questions I was asked every day was, "What did you do today for somebody else?" I did the service that was obvious to me — you have a friend who pulls you into it. It wasn’t until I owned my own bookstore cafe that I started to understand what was happening in my community and I began to see the opportunities.

U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., a social worker and lecturer in the School of Social Work at ASU: Everyone knows my family story. I went from a middle-class kid to a child who was homeless. What I remember most during those difficult times was the help that others provided to me. The help that people gave to ensure I made it to school every day and that I could see my dreams and future as a real prospect. When it was time to go to college, studying social work was not even a question. It was a duty. And the move from practical social work every day to an elected official was an extension of that. I have a tremendous debt to pay.

Finding satisfaction in service

Sinema: I made it to the place in life I am today because I received the benefits of service. When I say I have a duty and obligation, it’s to repay the debt but the service itself is a gift. There’s nothing more rewarding or meaningful than knowing you’re making a difference in the life of someone else and knowing you are helping them to have access to the American dream.

Mooney: If you connect service and social justice, that’s where you pull people in. People won’t sign up because "I’m going to get certain skills" or "I’ll get a certain amount of money." But if you connect it to other pieces of their life that they care about, that’s where it’s meaningful.

The crisis of civics education

Haines: As (the commissioners) went around the country, even though it was not part of our mandate, the reality is that we talked about the importance of civics education. One of our findings is that if you get a high-quality civics education, you’re more likely to engage in service. Overall, about 25% of students demonstrate proficiency in civics education. The amount of money we spend on civics education is astonishing. It’s about $54 per student on STEM education and about 5 cents for civics. Institutions have a role in training teachers in the content and in promoting it.

Public service in the federal government should be easier

Jonathan Koppell, dean of the Watts College for Public Service and Community Solutions at ASU: Young people who are interested in service and even in government service tend not to be interested in federal service. They gravitate toward local government more than national government. Even those who are interested in the federal government find the system of hiring and internships to be so impenetrable that they have a hard time even decoding it.

Sinema: It makes sense because the federal government is dysfunctional and broken. You can’t blame young people for saying, "I want to work in my community and see the fruits of my labor" or do work globally. It would help if the leaders of the federal government behaved like rational individuals who are focused on solving problems rather than scoring political points. I take issue with people who say to young people, "You should be more focused on serving in the federal government or on voting." What are we offering? We’re offering a broken, dystopian view. It’s up to us to provide a vision of how it should be fixed. One way is to highlight the leadership of those engaged in meaningful work at the federal level that makes a difference in people’s lives.

Haines: There’s a huge attack on federal public service right now. The morale for the federal civilian service is quite low, and it’s not perceived as the most attractive place to work. We do ourselves a disservice with the truly archaic hiring policies we have. We need to shift to a talent management system that’s flexible and recognizes that people don’t think about a 30-year career in one location and that allows people to come in from the private sector. And frankly we need a new generation to come in. We’re at the point where a third of federal employees will retire within the next five years and only 6% of federal workers is in the younger generation.

The pandemic could provide a bipartisan way forward

Sinema: As (Congress has) been working through this series of packages, what you see in the news are the parts that are acrimonious. What is less public is that each of the four packages that Congress has passed have been overwhelmingly bipartisan. I expect as we move forward, we’ll pass another two to three packages and I think there is a real possibility of moving forward on a service-related initiative that will create meaningful jobs for young people and can contribute to the recovery that we need in this crisis. There will be partisanship along the way, but I feel confident that we’ll behave in an appropriate way to resolve these concerns.

Top image by iStock/Getty Images