When we ask kids what they want to be when they grow up, “engineer” isn’t usually among the top answers. Being an engineer isn’t as obvious as a doctor, athlete, teacher or other common dream careers. However, all these jobs rely on engineers, computer scientists and other technology professionals.

Introducing engineering concepts in fun ways and meeting engineering students and professionals can spark young people’s interest in these careers.

In fact, engaging outreach activities led many current engineering and computer science students to study at the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University. Some now return the favor and mentor young students through these same programs.

A pipeline for the next generation

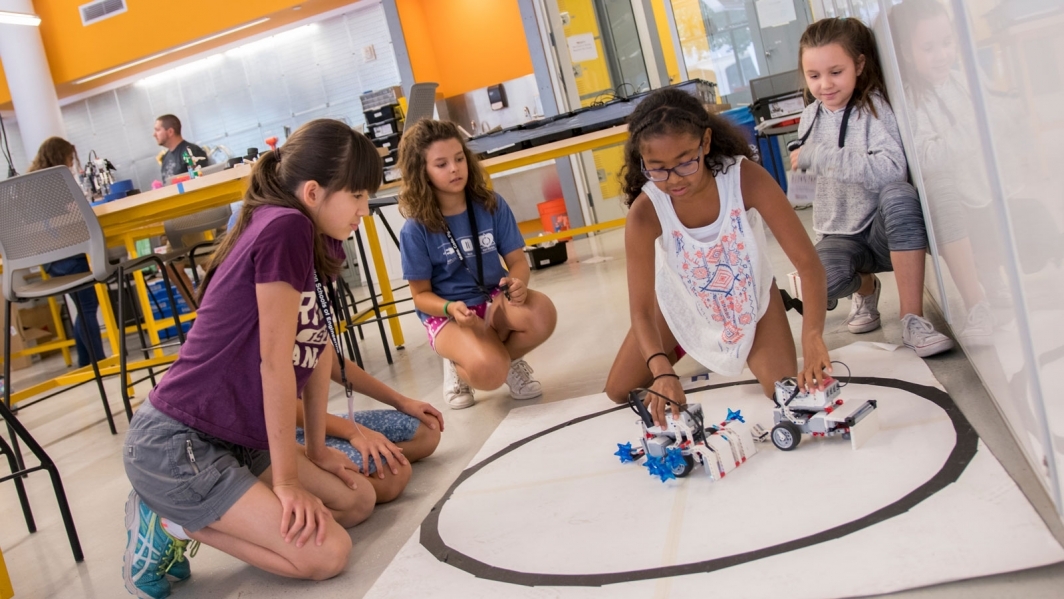

The Fulton Schools conducts school-year and summer outreach activities for children as young as kindergarten. Students can learn how to code, make video games, build robots, explore sustainable energy production — all fun ways to introduce concepts they may never have associated with engineering. For even the youngest students, the experience means getting to practice being an engineer and planting the seed that this can be their future.

“At the elementary level and younger, outreach is about raising awareness for engineering. It’s about what engineering is and what engineers do,” said Jennifer Velez, coordinator senior of the Fulton Schools student outreach and recruitment programs. “It’s tapping into that curiosity and giving kids an opportunity to explore and develop what we call engineering habits of mind, which include creativity, collaboration and problem-solving.”

The youngest students accomplish this goal by tinkering and exploring, whereas older elementary and middle school students start to learn skills and apply them in coding and robotics projects.

Velez says it’s important to generate interest in engineering early, so by the time students are in middle and early high school they are on a technical academic path and have the foundational skills that will help them accelerate their engineering studies in college.

Many summer programs take place at ASU’s Tempe and Polytechnic campuses, where the young participants get to see university life and interact with undergraduate students. The experience makes engineering and the possibility of college in general feel more accessible.

“This exposure gives participants a comfort level and familiarity with the university — and it demystifies college a little bit,” Velez said. “That’s especially important for students who are underrepresented in STEM. They have this opportunity to ask questions, especially of their mentors and role models who look like them.”

Regardless of what the participants go on to do, they cultivate a new mindset and learn valuable skills that can be applied anywhere.

An early start to engineering

Along with running its own outreach activities, ASU facilitates robotics programs in Arizona for the nonprofit organization FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology).

From kindergarten through 12th grade, students can participate in multiple levels of robotics activities — FIRST Lego League Jr., FIRST Lego League, FIRST Tech Challenge and FIRST Robotics Competition. The organization uses these programs to encourage students to pursue engineering and STEM careers, and to become leaders and innovators with a strong grasp of work-life skills for the 21st century.

Arizona FIRST Lego League aims to “ignite an enthusiasm for discovery of the basic principles of science, technology, engineering, arts and math” by tasking teams of students aged 9 to 14 to solve community problems through robotics challenges. In the past year, more than 2,700 students across the state have participated in Arizona FIRST Lego League.

The Fulton Schools outreach program holds weeklong FIRST Lego League summer camps for beginner and intermediate levels of robotics knowledge. The university also helps with team activities that run from August through December, as well as helping to coordinate statewide tournaments for more than 360 teams throughout Arizona, including state championship tournaments held on ASU’s Tempe campus each January.

“For kids who have been intimidated by (robotics) or haven’t had the opportunity to try it, the summer camp takes away the mystery and it develops their excitement for these different projects,” said Laura Grosso, senior coordinator for Fulton Schools student outreach and retention programs. “From the kids’ perspective, it helps give them the experience and foundation to move on to a team.”

Zach Smith, a first-year computer science student at ASU, says he knew he wanted a computer-related career as early as third grade. That’s when he began participating in FIRST Lego League in Flagstaff, Arizona, and realized not only could he become an engineer, but that elementary school wasn’t too early to start building his skillset.

Smith notes that learning to program a Lego robot to navigate through challenges helped him to pinpoint which area of computer science most interested him.

Grosso said, “People who have been through this program learn skills that are critical for engineers — not just the hard skills and the ability to understand complicated technical concepts, but the courage to tackle these really challenging areas of study.”

As Smith moved through the FIRST ranks and participated in the more advanced FIRST Robotics Competition during high school, he also strengthened his technical and teamwork skills.

He also became familiar with the college engineering experience as his team competed in tournaments hosted at ASU, where current Fulton Schools undergraduate students gave firsthand accounts about their experiences. Seeing what life could be like as a computer science student at ASU made him all the more eager to become a Sun Devil.

Seeing how engineering impacts society

While some students have an early interest in engineering, others get a later start.

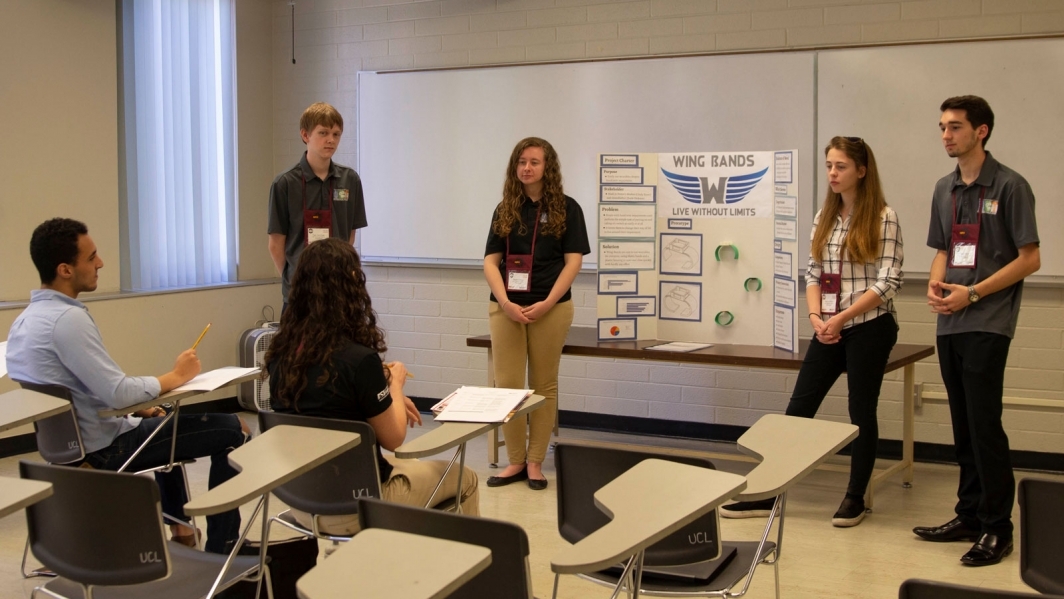

The Fulton Schools outreach team aims to help middle school and high school students see themselves as engineers through a beginner version of one of its college extracurriculars, the Engineering Projects in Community Service, or EPICS, program.

EPICS enables college students to solve real-world community challenges through service learning projects. The same concept is used by 10 middle schools and 19 high schools in EPICS High.

Some schools use the program as a way to introduce engineering to middle school and first-year high school students, while others use it to help advanced junior and senior students apply technical skills they’ve already learned over the course of their STEM education, or anywhere in between. More than 700 students currently participate in EPICS High in Arizona.

Typically, students work with their teachers and not-for-profit organizations to make an impact in their community with engineering concepts and human-centered design skills.

“Students can deliver a complete project, and it is important at that age for them to experience failure, learn to push through failures and iterate to deliver something,” Velez said. “It allows them to feel good about their success, which is a strong motivation to continue into engineering.”

Seeing how engineering tackles issues that students see in their own communities also helps them create an engineering identity and see themselves in engineering careers down the line.

Some EPICS High groups also have ASU student mentors helping to guide the middle- and high-schoolers to learn skills they need to create successful community solutions.

Seth Mazza, a second-year aerospace engineering major in the Fulton Schools, was already interested in engineering, but his two years of EPICS High experience at MET Professional Academy in Peoria, Arizona, gave him a new perspective and motivation to pursue it as a career.

He worked on two projects: a modular electric piano keyboard and an elastic wristband to help people with hand and arm impairments more easily use wearable devices.

“One of the most memorable moments for both of these projects was reaching out to potential stakeholders and getting real validation of the idea,” Mazza said. “These experiences also made me want to attend ASU even more and join the EPICS program at the college level.”

Creating a culture of giving back

Not only did their experiences help lead Smith and Mazza to study computer science and aerospace engineering at ASU, they also encouraged them to give back and return to the same outreach programs as mentors.

“Students who had an EPICS High mentor seem more likely to become mentors themselves,” Velez said. “They value those relationships.”

Velez says when students come back to mentor in the same program, it shows how influential and valuable the experiences were when the mentors were participants.

“It shows how involved and invested they were in their projects when they were in EPICS High, and now they’re excited to help other students get the same kind of experience.”

Mazza, who has now been an EPICS High mentor for two years at the same high school he attended, exemplifies this idea.

“I wanted to make sure other EPICS High students gained everything I did in the program and more,” he said. “I can help them through the rough patches of a project without taking away the learning experiences.”

Mentors also feel like they’re making a difference in the lives of others, and for themselves. For Mazza, mentorship is often an inspiring experience.

“Any day where I can get students to come to some sort of realization and figure out what they were stuck on or missing is a great day,” Mazza said. “The way their faces light up when they reach said realization alone, is enough to make me want to continue being a mentor.”

For others, helping people is the core value they are most drawn to. FIRST programs emphasize the importance of support just as much as technical skills.

FIRST mentors — who range from high school and college students to industry professionals — play a key role in imparting the value of teamwork. Smith’s FIRST mentor was a high school student who ended up earning a master’s degree in software engineering from ASU. Smith remembers his mentor’s enthusiasm influenced his desire to “pay it forward in the future.”

Now, as a mentor himself, Smith works with his FLL team of elementary school students who are the same age he was when he started participating. He teaches them important lessons for all areas of robotics competition: robots, research projects and core values.

Like the college students he met at youth competitions hosted by ASU, Smith also enjoys talking with teams and “showing the kids that college is something they can attain in the future.”

Overall, it was a valuable experience when he was in third grade, and it continues to be rewarding as a mentor.

“Seeing these students grow in the same way I did gives me hope for future engineers,” Smith said. “I know they have the skills necessary to solve the problems of tomorrow.”

Top photo: Elementary and middle school students participate in the FIRST LEgo League state championship tournament held at Arizona State University. Outreach programs such as FIRST Lego League and Engineering Projects in Community Service for middle and high school students, known as EPICS High, help introduce complex engineering concepts in a fun way starting at an early age. Photo by Connor McKee/ASU

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1744539. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

More Science and technology

New NIH-funded program will train ASU students for the future of AI-powered medicine

The medical sector is increasingly exploring the use of artificial intelligence, or AI, to make health care more affordable and to improve patient outcomes, but new programs are needed to train…

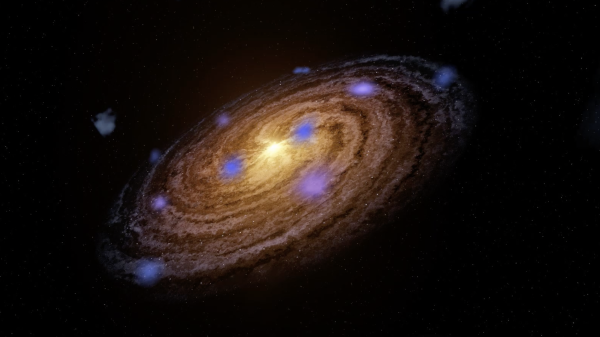

Cosmic clues: Metal-poor regions unveil potential method for galaxy growth

For decades, astronomers have analyzed data from space and ground telescopes to learn more about galaxies in the universe. Understanding how galaxies behave in metal-poor regions could play a crucial…

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…