We don’t always think about the insect world buzzing below our feet. But the health of those tiny, complex societies gives us important clues about the health of the planet at large.

In research published this week, Arizona State University alumna Lauren Welch examines how the foraging habits of leaf cutter ants could change with global warming, and what that means for humans.

Leaf cutters are a tropical species appearing in South and Central America, and parts of the American South. Welch first came across the species while on a study abroad program to the Panamanian rainforest through the School of Life Sciences in The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Launched in 2014 through a partnership between ASU and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, each summer Experimental Tropical Biology gathers around 12 students to spend two to three weeks doing a field study of their choice. Welch went during the summer of 2018 and remembers noticing leaf cutter ants right away.

“Leaf cutters stuck out to me in Panama because they're just very ubiquitous, whether you're near the school grounds where we stayed, or deep into the actual rainforest, they’re always there,” said Welch, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences in 2019.

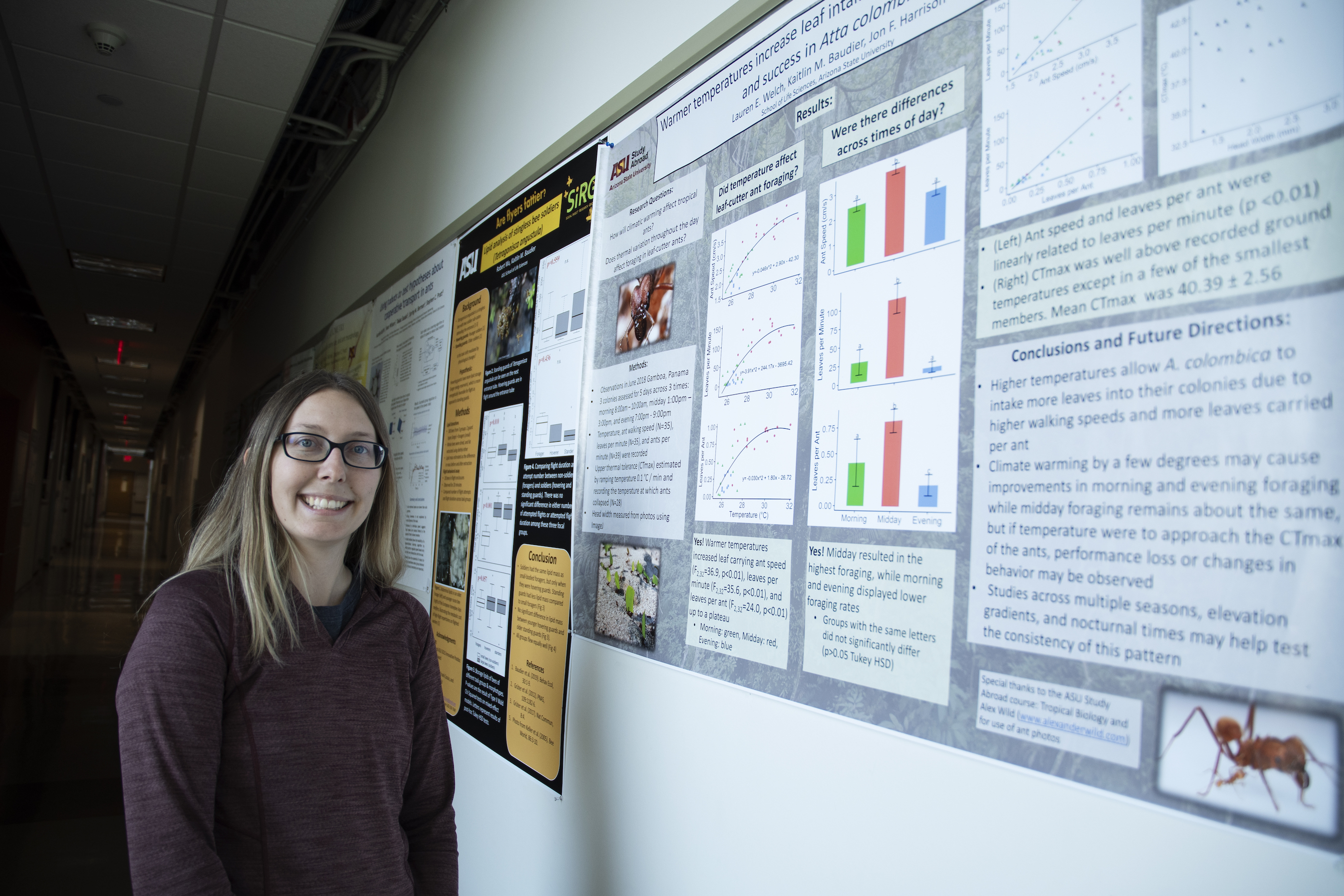

School of Life Sciences alumna Lauren Welch recently published research examining how the foraging habits of leaf cutter ants could change with global warming.

The heat factor

Using a pair of powerful, scissorlike mandibles, leaf cutters tear pieces of leaves and other foliage and haul the load back to underground colonies. As the material decays, the ants break it down to harvest a fuzzy white, nutrient-rich fungus used to feed their offspring.

In Panama, Welch began to wonder how factors like heat and sunshine affected this process.

“By counting both the number of ants coming in and the leaves they were carrying, we wanted to understand the temperature and time of day they were most successful,” Welch said.

Her findings, which now appear in the peer-reviewed journal Insectes Sociaux, suggest leaf cutters active during Panama’s rainy season from May until December increase foraging speed and success as the day gets progressively warmer, thus reaching peak leaf intake during midday.

“Being there during the rainy season meant even midday temperatures were moderate, so midday was when we were hitting what turned out to be a great temperature for the ants because it wasn’t so hot they had to stay inside, but just warm enough to increase their productivity.”

Insect impact

Some might wonder why something like leaf cutter foraging should matter in the human world. Welch said understanding these patterns could help us plan for the future, especially as global temperatures continue to climb due to climate change.

“First of all, these ants are social insects, so understanding their patterns could help us better understand other social insects like bees,” she said. “Plus, the leaf cutter variety I studied, Atta colombica, is considered a pest species because their mass foraging causes problems for crops. If they are going to be even more productive in the heat, we need to start thinking about what that means for farmers, forests and other ecosystems.”

Kaitlin Baudier is a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Life Sciences who co-instructed Welch’s summer session and co-authored her research in Insectes Sociaux. She said leaf cutters play a complicated role in the overall health of tropical ecosystems. Tracking their progress could serve as a marker for what’s to come for the greater natural world.

“Leaf cutters are often called ecosystem engineers because they make these tremendously huge colonies and circulate a lot of soil. But they also defoliate a lot of plants and cause problems for farmers and loggers,” she said. “They can be used as a social model for thinking about the complex social ramifications of big temperature changes — in an ecological sense, they are an important keystone without which things are surely going to change.”

Baudier said Welch’s data suggests warmer temperatures will benefit the ants in the short term, but that could change as heat rises more severely during Panama’s warmer dry season.

“We found that with warming temperatures there might actually be an increase in productivity in the cooler times of day and cooler times of year because temperatures are going to be warmer but not too warm,” she said, “But in the warmer times of year, their foraging speed may already be maxing out and thus potentially even be worse by midday.”

Research already exists on leaf cutter habits, but Welch’s work adds valuable field data that might otherwise not be observed in a lab.

“Existing literature suggests this species chooses to forage at different times of day depending on the season, but Lauren’s research asks whether light and temperature each play a role in that process as well,”she said. “She measured how well they forage, intake food and run in relation to the environmental temperature. That's important especially because she was able to get all these data collections right in the field with naturally-occuring colonies.”

Student research

From left: Jon Harrison, Lauren Welch and Kaitlin Baudier.

After graduating, Welch became a Mackenzie Fellow at Audubon Arizona, where she helps organize trips through Phoenix nature preserves for local elementary school students. Her day-to-day looks a lot different now than in Panama, but she said the skills she learned doing field research and drafting the subsequent paper continue to play a role in her work today.

“One of the biggest things I took away from the trip was learning how to look around and appreciate everything,” she said. “I've always thought of myself as a scientific thinker, but actually going through the process of creating a hypothesis and testing it, then doing all of the background research to write up a paper, I’ve definitely applied what I've learned to everything I've done since.”

Welch’s project isn’t the only one to see publication. Previous trips have seen students pursue and publish research measuring tropical trees and plants, exploring the defense mechanisms of nonstinging bees and counting the number of animal species in main thoroughfares.

Jon Harrison is a professor in the School of Life Sciences who has led the Panama program for the last five years. He said the tropical location and the autonomy of the course allows multifaceted research to thrive.

“Anyone interested in becoming a biologist should go to the tropics at least once, because it's very different from most of the U.S., Europe or Canada in terms of biodiversity,” said Harrison, who also co-authored Welch's research. “Given the biodiversity there and its importance to all the global cycles, it’s really valuable for our students to actually experience it on the ground.”

Harrison estimates a handful of students from each summer program go on to pursue publication, a percentage of whom appear as the paper’s first author like Welch. But regardless of whether students take that next step, Harrison said all participants walk away with a different perspective on the natural world.

“I don't think we've ever had a student come back without a much stronger appreciation for the tropics, for bugs, trees, and just the overall process of creating research,” he said. “To me that’s the most rewarding thing to see, because it’s this attitude of questioning and trying to come up with answers — it's more like an approach to life.”

Written by Alisa Reznick

More Science and technology

Podcast explores the future in a rapidly evolving world

What will it mean to be human in the future? Who owns data and who owns us? Can machines think?These are some of the questions pondered on a newly launched podcast titled “Modem Futura.” Co-…

New NIH-funded program will train ASU students for the future of AI-powered medicine

The medical sector is increasingly exploring the use of artificial intelligence, or AI, to make health care more affordable and to improve patient outcomes, but new programs are needed to train…

Cosmic clues: Metal-poor regions unveil potential method for galaxy growth

For decades, astronomers have analyzed data from space and ground telescopes to learn more about galaxies in the universe. Understanding how galaxies behave in metal-poor regions could play a crucial…