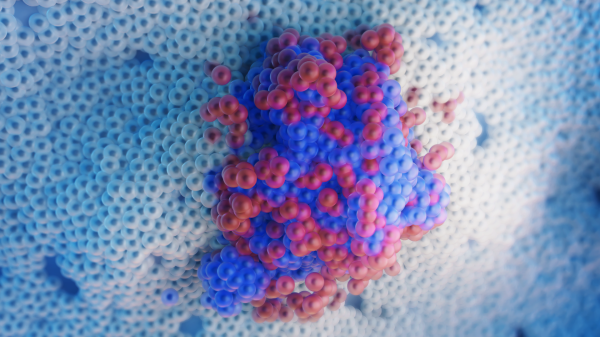

Mother-baby microbiome rush at birth can have lifelong health impact for the infant

Efrem Lim is a virologist who studies host-virus interactions in human health.

Every mother wants to give her newborn the very best start. During the nine months of gestation, women understand that eating right, breathing fresh air, exercising and maintaining a positive mindset during pregnancy are important to giving birth to a healthy baby. But many do not know just how important the very moment of birth is in shaping the infant’s long-term well-being.

This is a pivotal time when a massive amount of the mother’s microbes are being actively transferred to the newborn. Yet, remarkably little is known about how gut bacteria and viruses are acquired by infants.

Now researchers at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics, are working to understand how and when these microorganisms assemble and the early-life factors that affect their progression.

Efrem Lim, a virologist who studies host-virus interactions in human health, teamed up with Lori Holtz, a pediatric gastroenterologist at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and a team of researchers to study bacteria and viruses at the moment of birth. Recently, Microbiome Journal published their work, "Discordant transmission of bacteria and viruses from mothers to babies at birth."

According to Lim’s publication, “the gut undergoes a profound transition as the infant leaves the near-sterile or sterile womb and becomes home to diverse microbial populations.”

The rush of microbes at birth can have lifelong effects

Research has found that infants’ gut microbiomes can shape their metabolic and immune-related health, as well as their lifelong risk for obesity, asthma, allergies and autoimmune diseases.

Microbes program the immune system, providing important nutrients to our cells that fight off harmful bacteria and viruses, so this sets the stage for the baby’s future health. From the time a baby is born until about age 2 or 3, the microbiome and virome are highly dynamic, with large shifts in the microbial community as it develops.

The human body harbors trillions of microbial cells that are believed to be important for human life. Use of antibiotics or dietary changes can disturb the microbiome and drastically shift our microbiomes. However, the microbiome is able to recover back to a similar healthy state after the disturbance. The microbiome has remarkable resilience.

“There are still many illnesses affecting newborns through early childhood development,” said Lim. “We need to improve the health and well-being of infants and future generations.”

“We need to better understand what influences the transfer of the microbiome from mother to baby,” Lim said. “To date, we have been able to understand what typically happens in healthy infants. This knowledge gives us the foundation to probe more deeply into how colonization and maternal microbiome inheritance affects diseases – information that could be important for premature birth and complications such as necrotizing enterocolitis, a devastating intestinal disease that affects premature babies.”

Untangling microbes from viruses

“Most of what we know about the microbiome, their health benefits and impact on human disease is largely based on the role of the bacteria in our microbiome,” said Lim, who is also an assistant professor at ASU’s School of Life Sciences. “Very little is known about whether the viruses are functioning in the same way.”

Viruses are very simple microbes — among the smallest microbes on earth. In order to survive and grow, viruses find their way into living cells. They can damage healthy cells, causing disease.

“Prior studies found that the majority of the infant’s bacterial microbiome is inherited from their mother,” Lim said. “And here we found that only a small portion of the infant’s virome matches with their mother.”

Lim and his team found that related infants shared a more similar gut virome and bacterial microbiome to their twin than to unrelated infants.

“Our findings support that the newborn’s gut viruses are likely sourced from other environmental exposures.”

Lim adds that this may be why each twins’ viromes are more similar to one another than to other unrelated infants.

Video produced by researchsquare.com

Does delivery mode make a difference?

People have theorized that this process can be affected negatively or positively by mode of delivery, the choice between formula or breast milk feeding, perinatal antibiotics and taking probiotics during pregnancy.

“We found that microbiome interactions of infants born by C-section delivery varied from infants born by vaginal delivery, showing that different bacteria and viruses were at play depending on delivery route,” he said. “However, the mode of delivery did not significantly influence how much of the infants’ microbiome was inherited from their mother. In other words, the mother still had a large influence in seeding the infant’s microbiome.”

According to Lim, the study touches on two major ideas.

In terms of early life development, recent studies are converging on findings that the maternal gut microbiome is the source of the majority of the infant’s microbiome. So, the expectation is that viruses should likewise follow suit.

However, the study shows that much less of the virome is acquired from the mother as compared to the bacterial microbiome. This means that the rules of life are fundamentally different between bacterial and viral transmissibility at birth.

The impact of delivery route — vaginal compared to cesarean delivery (C-section) — is another area of intense interest with conflicting reports.

Newborns delivered through C-section are associated with increased likelihood of asthma, allergies and other immune disorders. The question has been how much of that is due to differences in microbiome acquisition from the mother.

Some studies report that the microbiome of infants born from vaginal delivery differed from C-section. Others find that these differences only appear several days after birth or were minimal. Collectively, this has led to a practice of vaginal seedingThe American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend vaginal seeding outside of an IRB-approved research protocol due to the limited data about safety and efficacy available. by swabbing a newborn infant with vaginal fluid to transfer vaginal microbes from the mother to the infant.

As a follow-up to this study, Lim is seeking to understand how the mother’s health influences early microbiome transmission and whether the virome impacts neonatal diseases.

Written by Dianne Price

More Science and technology

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would…

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to…