It’s only fitting that the literature produced by citizens of a country predicated on the idea of personal and societal freedoms should reflect those deeply entrenched values.

From “Huckleberry Finn” to the 1950s Beat Generation, the American literary canon abounds with themes of oppression, the desire to escape and the search for a better life. Yet too often, says Arizona State University Associate Professor of English Joe Lockard, the major influence for these stories is overlooked: the American slave narrative.

In 2003, Lockard established the Antislavery Literature Project to make accessible a range of antislavery literature as an educational tool. Now, in cooperation with faculty from Xi'an Jiaotong University, he and his colleagues are celebrating the project’s latest accomplishment — the publication by Shanghai Jiaotong University Press of two volumes of American slave narratives, translated into Chinese.

As part of an earlier initiative called Project Yao, which Lockard undertook with Sichuan University to create a binational database of American literature translated into Chinese, he realized there was a gross lack of antislavery literature, considering its massive impact.

“What became very clear was the underrepresentation of African American and other minority literatures in the United States,” Lockard said. “So this translation series works to address that absence. There's a very strong interest in Chinese universities in American literature, and particularly in multiethnic literatures of the United States.”

Joe Lockard

Shih Penglu, a professor at Xi'an Jiaotong University, co-edited the series with Lockard. She remembers having dinner with him at a Tex-Mex restaurant in Chengdu, China, in 2009, when she was a PhD candidate at Sichuan University and he was there to work on Project Yao. Over their meals, Lockard shared with her the story of former slave Harriet Jacobs, who spent seven years hiding in an attic before escaping to freedom.

“I was so much touched and saddened by it and felt an immediate sense of mission,” Shih said. “It was just as simple as that: He shared Jacobs’ story and I came on board … the Antislavery Literature Project.”

Jacobs’ “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” was the first narrative they translated for the series, and it was published in 2015. Shi said that since its publication, she has noticed an increase in master’s theses and doctoral dissertations on slave narratives among Chinese students — not only within the domain of American literature studies, but also world history and law — and says that this upward trajectory is still on the rise.

“Intrinsic ideas in these texts, like the condemnation of slavery and the unswerving pursuit of freedom, speak to current minds, inviting thoughts about the past and the future of human history,” she said.

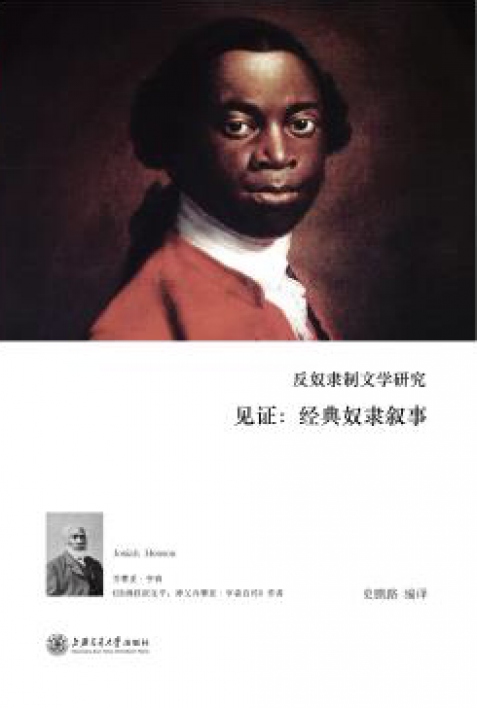

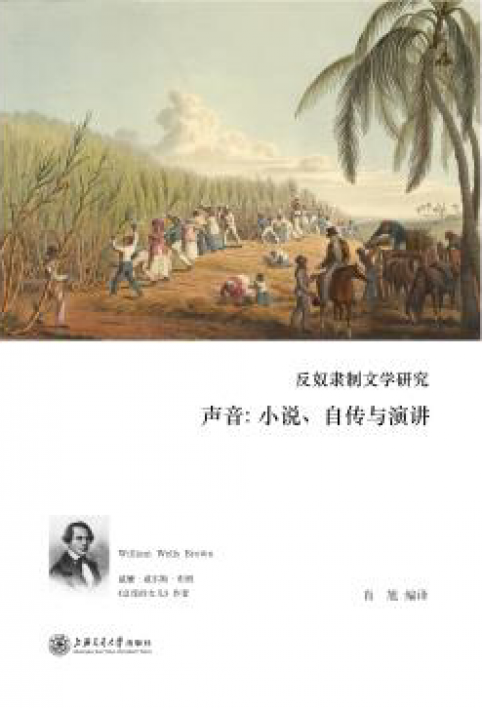

This latest publication in the series, titled “American Slavery Literature,” comprises two volumes, consisting of seven narratives, including “Clotel; or, the President's Daughter” by William Wells Brown, inspired by the lives of Thomas Jefferson’s children with his slave Sally Hemings; “Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life” by Josiah Henson, who would later become the title character of the Harriet Beecher Stowe novel “Uncle Tom's Cabin”; and “Appeal to the Coloured People of the World, in Four Articles” by David Walker, in which he urges enslaved people to rebel.

In the preface to the series, Lockard writes, “Choosing representative texts for this was a challenge. There was no fully satisfactory selection.”

With the exception of translation editions of works by Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass (whose 1845 memoir the series also includes), Lockard said, the study of this body of literature was almost completely devoid of Chinese-language resources until the publication of this series, so they took care to incorporate a variety of voices.

Each publication in the series includes an introduction in order to provide historical and biographical context, as well as a cross-cultural teaching guide that addresses not only students but also teachers.

“How do you get a discussion going about the literature of American slavery in a Chinese classroom?” Lockard asked. “That can be difficult. There are a lot of misconceptions to overcome, misinformation. So we looked for points of comparison between American experience and Chinese experience.”

One parallel many Chinese students will recognize is that of displacement created by capitalism, thanks to the “coolie” trade that took place during the 19th and early 20th centuries, which forced thousands of Chinese into indentured labor in the Caribbean. Another is how the sexual exploitation of female African American slaves mirrors the not-so-distant history of Chinese women working as servants in wealthy households.

“One thing we fail to recognize is how close this history is in China,” Lockard said. “(Americans) are several generations removed. In China, it's Grandma.”

In addition, he expects the issue of literacy in slave narratives to resonate with Chinese readers, many of whom have family members, usually grandparents, who never received a formal education.

“When we talk about points of comparability, the issue of how we learn to read and write and what freedom that gives us is powerful in a Chinese classroom in ways that American classrooms would not understand,” Lockard said.

His own grandparents were born and raised in czarist Russia, where they were forbidden to attend their village school because they were Jews. Eventually, they learned to read and write through informal instruction, and then passed down to their family a love of education and an understanding of its empowerment.

Lockard relates that when teaching in China, he has asked students to raise their hands if any of their grandparents did not go to school, raising his own hand first.

“A heavy majority of students raised their hands, and we talked about how Frederick Douglass could not attend school but valued literacy so much, and about how in studying, we honored the lives and struggles of our grandparents,” he said.

Lockard says he has long been interested in the idea of freedom and how to get it, and how literature helps answer that question. In 2009, he founded what is now the Prison Education Program at ASU, in which faculty members, graduate students and staff work with the Arizona Department of Corrections to offer classes to prisoners.

“Slavery and prisons both fall within the rubrics of confinement and freedom, and the questions that attach,” he said. “How do people express themselves when faced with these things? It's an important social question that we ignore at our peril.

“We read literature to understand the world. We communicate values through literature. One of the values we talk about in this series is freedom. I don't want to define freedom for you; I want you as a student reading this to define freedom for yourself.”

Top photo courtesy Pixabay

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor explores theater, dance for young children in new book

Arizona State University Assistant Professor Amanda Pintore believes in the artistic capacity of very young children. She's hoping to spread that awareness to others with the recent publication of…

Petroglyph preserve celebrates 30th anniversary with ancient, modern tales

The Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve provides a beautiful walk through a pristine desert where chuckwalla lizards are as plentiful as the cacti that comes in many shapes and sizes.It’s also a step…

Kaleidoscope short film contest inspires powerful binational filmmaking in its second year

“We come to this country not to steal anybody’s jobs but to take advantage of the opportunities that the rest ignore. We’ve been taking care of the American soil for many years. But our hands will…