Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2019.

Whether you’re a bacon fanatic, a vegan or somewhere in between, the choices you make about the foods you consume reverberate much further than your own body. As more consumers become aware of this, demand for sustainably sourced foods is on the rise. Yet personal health remains an important consideration.

So how does the average consumer weigh both the nutritional quality and the environmental impact of a food? Until now, they couldn’t. But thanks to recently published research that included ASU College of Health Solutions professors Carol Johnston and Chris Wharton as authors, there now exists the basis for such a tool.

Chris Wharton

“This paper is as much about consumers making choices right now as it is about the future of protein,” Wharton said. “Because this is one of the most important sustainability questions of our time.”

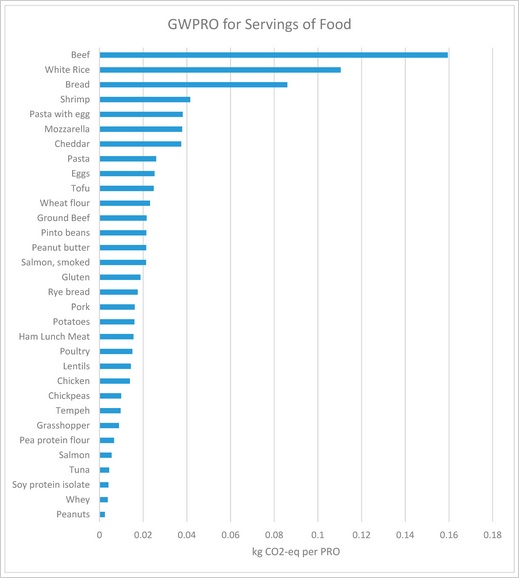

Hoping to address the growing conundrum, Wharton, Johnston and colleagues built an algorithm to assign a score to some of the most commonly consumed protein-rich foods and rank them based on their efficiency at delivering the most protein at the smallest cost to the environment.

Protein values were calculated taking into account its bioavailability, which refers to the fact that protein is absorbed differently depending on what food it comes from. Generally, protein from animal foods is easier to absorb than protein from plant foods because plant sources are often high in fiber that acts as a barrier to digestion.

Environmental impact was calculated through life cycle assessment (LCA) analysis, which determines a food’s environmental impact by accounting for a variety of measures in the life cycle of a food product, from production to consumption to disposal.

Researchers focused on protein-rich foods because protein is not only one of the most important factors in a healthy diet, but also where most resources go in terms of food production.

“There’s consensus developing now around how existential the climate crisis is,” Wharton said. “Central to that is our food production system, and then, vital to that is how we produce protein.”

What they found was foods like peanuts and protein powders were most efficient at delivering protein with a small environmental cost, while cheeses, grains and beef were least efficient.

“You can almost think about it like how you teach your kids what kinds of foods are ‘sometimes’ foods and what kinds of foods are ‘all-the-time’ foods, when it comes to fruits and veggies,” Wharton said.

“We can do the exact same thing with proteins now. You can say, beef and white rice, these sorts of things are ‘sometimes’ foods; they're indulgences. You have those once a week or less, maybe once a month. But peanuts and chicken and those sorts of things, you can eat those on a weekly basis. It helps people make those decisions.”

The fact that protein powders ranked so high in efficiency was surprising to the researchers, because they contain whey, an animal product.

But, Wharton reasoned, that could be because there are two major contributors to environmental impact when it comes to protein-rich foods: on-farm contributors, such as crop fertilizers and gas emissions, and manufacturing contributors.

“So some of these products that are plant-based but require processing could end up having more of an environmental impact than you realize,” he said.

In the case of whey, its surprising ranking derives from a quirk in its LCA that attributes less environmental impact to dairy products than beef products.

GWPRO (Global Warming Potential Ratio) is GWP in kg CO2-eq per serving divided by PRO per serving to capture the protein content and quality in the environmental comparison of protein sources. Standard deviation is not reported here as values are the result of a ratio with PRO. Foods with higher GWPRO are less efficient at delivering protein while having little environmental impact. Chart courtesy of Sustainability academic journal

Salmon and tuna also ranked high for efficiency, but only when they were wild-caught.

“In our minds, we might think, ‘OK, animal proteins, probably bad for the environment. Plant proteins, probably good for the environment.’ But if you're considering quality and environmental impact simultaneously, it's not as clear cut,” Wharton said.

Researchers believe the rankings could be extremely useful for those who have tried to adopt vegetarian or vegan diets but failed.

“We have some other research that shows very few people striving to be vegetarian or vegan achieve it long-term,” Wharton said. “But maybe it doesn't have to be so absolute. I kind of want to break the norm of absolutism in dietary choice and restriction. I think you could be plant-forward and eat beef only really rarely and eat tuna and salmon quite a bit more often and chicken here and there, and you're achieving a diet that's more sustainable and of high protein quality, maybe even more so than your standard vegetarian, who's totally committed.”

The rankings could also be useful when determining what kinds of foods to send in aid for those in need around the world.

“In the U.S., we have a lot of food,” Johnston said. “But if you go around the world, there's a lot of protein malnutrition. And if you're going to be feeding these billions of people outside the U.S., you can't feed them something that isn’t sustainable.”

In addition, certain populations who are known to be protein deficient, such as the elderly and vegetarians, could benefit. Johnston and Wharton have pitched two studies to the USDA to pursue research along those lines.

“Right now, there's just one recommended dietary allowance of protein for everybody,” Johnston said. “Regardless of whether you’re elderly, young, a vegetarian or an omnivore.”

But previous research of hers found that vegetarians in particular should be consuming at least as much as 20% more than omnivores, due to the low digestibility of protein from plant food sources.

Carol Johnston

This was a first-time collaboration for Johnston and Wharton, who specialize in vegetarian nutrition and food systems sustainability, respectively. Both agree their findings wouldn’t have been possible without an emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration.

“This is a cross-disciplinary question that requires a lot of different expertise,” Wharton said. “I feel like it’s a perfect example of how ASU ought to and does operate, pulling people together who have these different skill sets to come up with practical solutions to real-world problems. Because the food system is central to our survival on the planet.”

Top photo courtesy of Pixabay

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…