The acronym DOWM is a trope many scholars of Western canon are familiar with. It refers to the argument that the body of literature, music, philosophy and art that represent Western culture is disproportionately dominated by the work of “dead, old white men.”

Looking back on her life, Arizona State University Professor Emerita of English Laura Tohe sees evidence to support this.

As a child growing up in the remote community of Crystal, New Mexico, in the Navajo Nation, Tohe relished trips to the library, the main form of entertainment in a household with no television. She devoured works by Edgar Allan Poe, Nancy Drew mysteries and “Batman” comic books — a literary weaning on stories about white people, written by white people.

“When I was about 12 years old, I wanted to be a writer,” Tohe recalls. “But I didn't know how I could do it. … I thought only white people could be authors.”

Later, at the University of New Mexico, she took a writing course with Rudolfo Anaya — author of the renowned Chicano coming-of-age novel “Bless Me, Ultima” — who encouraged Tohe to look to her own family’s stories for inspiration.

“This light bulb went off in my head and I realized, ‘You know, he's right. I've always been surrounded by storytellers,’” she said.

Today, Tohe is an award-winning, critically acclaimed poet who has written and co-authored five books, several essays and two librettosA libretto is the text used in an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical., the most recent of which, “Nahasdzáán in the Glittering World,” will premiere at the Rouen Opera House in France on Tuesday, April 23.

The premiere comes on the heels of her participation in the Tulsa, Oklahoma, City-County Library’s Festival of Words in March where she was honored with the Tulsa Library Trust’s “Festival of Words Writers Award,” joining the ranks of such past recipients as Leslie Marmon-Silko, Vine DeLoria Jr. and Joy Harjo.

The award is the first and only such given by a public library to honor an American Indian writer. Teresa Runnels, coordinator for the library’s American Indian Resource Center, said Tohe was chosen as this year’s recipient because of the variety and scope of her repertoire.

English Professor Emerita Laura Tohe, Navajo Nation Poet Laureate, poses for a portrait at her Mesa home. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

The purpose of the award, Runnels said, is “to give recognition to American Indian writers in the hope that more will come along, because there’s not a whole lot. And also to recognize the hard work that these writers go through to tell their stories.”

Tohe attended the daylong festival in Tulsa with her son, Dez Tillman, who accompanied her on guitar for a spoken word performance of some of her rain-themed poems. Before that, they were welcomed by a traditional drum group and a chorus of Pawnee Public School children singing renditions of The Beatles’ “Let it Be” and the theme song to “Rocky” in their native tongue.

Tohe called it “an incredible, moving and beautiful experience,” adding, “I'd never been honored quite that way before.”

Having a poet as a mother never fazed Tillman when he was young, even though he often went along with her when she led writing workshops and taught at the university. It wasn’t until he became an adult that he realized she was doing something special.

“It’s really cool to see her blossom on this journey,” he said. “It’s like she’s been planting seeds since I was a kid, and now it’s all coming to fruition and she’s being recognized for her work as one of the main voices for Native people in this country.”

Tillman sees his mother as an inspiration for American Indian writers to join in and add their part to the narrative of Native people in America. And he’s not wrong; as the Navajo Nation Poet Laureate, for the past two summers Tohe has participated in a weeklong writing institute for Navajo youth at Navajo Technical University in Crownpoint, New Mexico.

“For the younger generation of Navajo writers, this is their first real opportunity to have teachers who are Navajo, who are published, who are giving these workshops, and they’re embracing that and participating in it,” she said.

Like Tohe’s most recent publication, “Code Talker Stories,” an oral history book about the remaining Navajo Code Talkers, almost all of her work is influenced by her cultural history, and much of it is influenced by her family.

Visits with her relatives were always punctuated by stories.

“When you visit family, that’s the first thing you do, is start telling stories, even if it's something minor, like, ‘On my drive into Gallup I saw a prairie dog standing on the side of the road,’” she said. “This is a way that we share our lives with each other, through storytelling.”

The first creative writing piece Tohe wrote in college relayed a story her mother told her and her siblings on childhood trips from the reservation into town for supplies. It was the tale of a brother and sister who, neglected by their parents, turned into prairie dogs; hence the animal’s human-like penchant for standing on its hind legs.

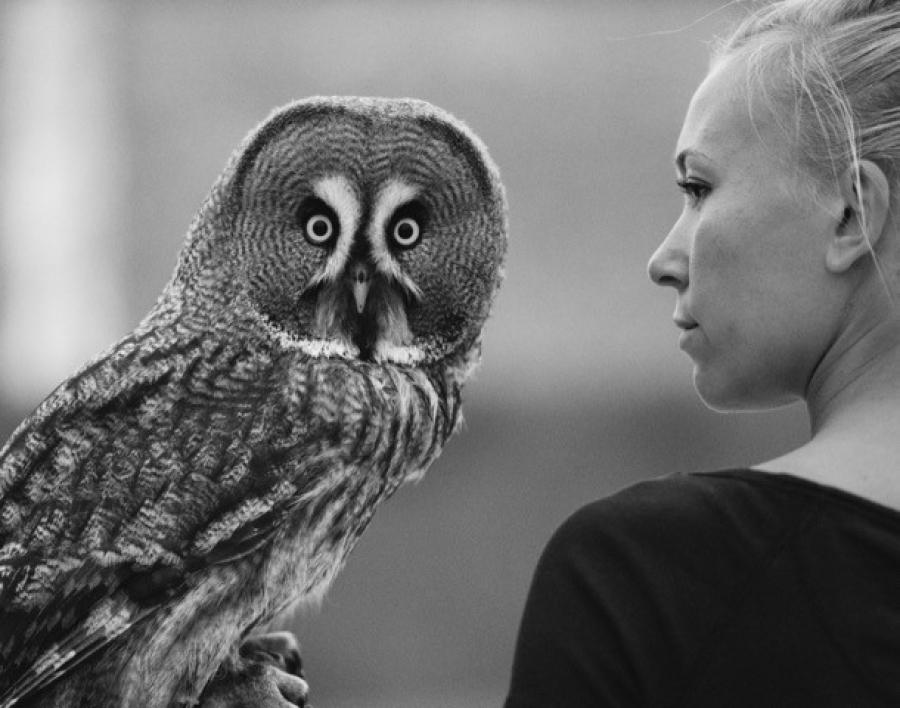

Animals often play a role in Tohe’s work. The upcoming presentations of the oratorio “Nahasdzáán in the Glittering World,” a sort of small-scale opera for which she wrote the text, will feature live animals, including an owl and a wolf.

“Nahasdzáán” translates to “Mother Earth” in Navajo, and according to their culture, the “glittering world” is the age we are presently living in. The piece confronts the Earth’s current state of climate change-induced distress and the need for it to heal.

“Animals are an integral part of this world that we live in and Native peoples have always revered them as relatives,” Tohe said. “Humans have caused a lot of destruction to the air and water and to the ground, and we need to stop and also look at how this affects not just humans but the animals as well.”

“Nahasdzáán in the Glittering World,” is her second libretto, having been commissioned by the Phoenix Symphony in 2008 to write the text for “Enemy Slayer: A Navajo Oratorio.”

The transition from poetry to music was a natural one for Tohe.

“Poetry is a lot like writing music,” she said. “You have to listen to the sound of the words, and you're concerned with line length and with the rhythm of the language.”

The realm of music is one she intends to explore further, through future collaborations with her son. Right now, they’re looking to record Tohe reading her poetry against a backdrop of original music composed by Tillman. They hope to have something completed within the year.

Top photo: ASU Professor Emerita of English Laura Tohe at her home in Mesa, Arizona. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

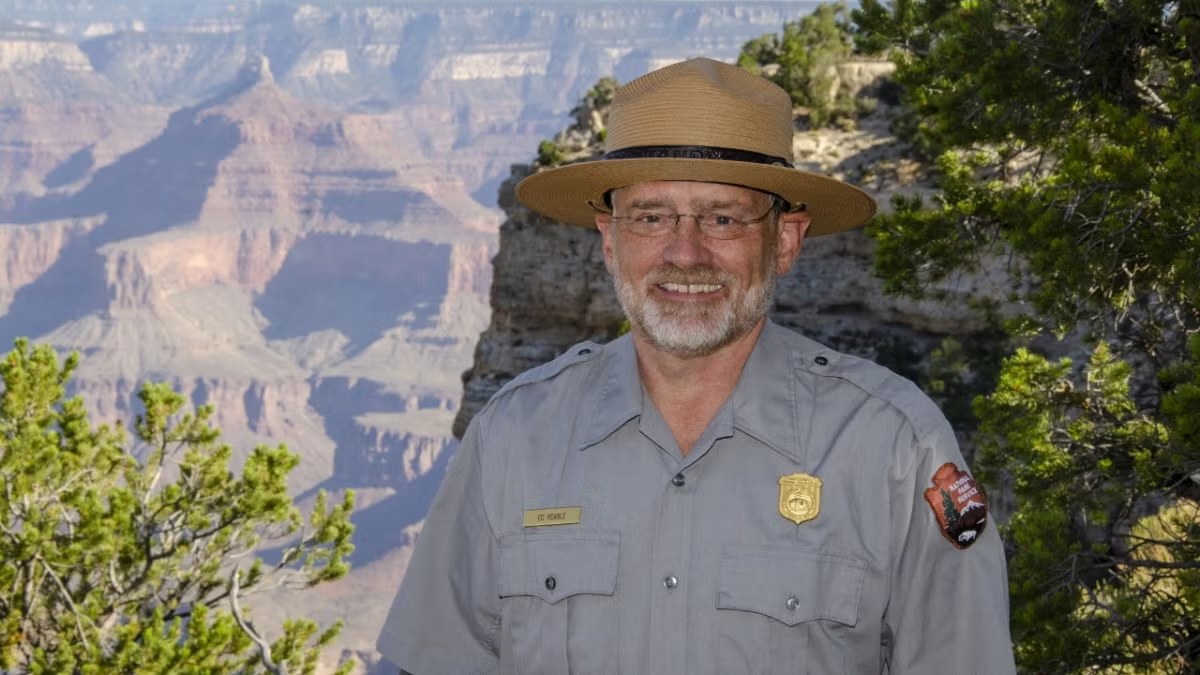

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…