Love and loss in the Grand Canyon

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2019.

Editor's note: This story is part of an ASU Now series celebrating the centennial of the Grand Canyon National Park.

The Grand Canyon has incredible power.

It united three backpackers with a shared passion, then separated them in tragedy.

Ultimately, it elevated them.

***

Andrew Holycross is the third person to have walked the length of the Grand Canyon on both sides of the river, and the ninth to thru-hike the canyon. A thru-hike is walking from Lees Ferry at the eastern end to Pearce Ferry at the western end (or vice versa) in one continuous push, without leaving the canyon.

Thousands have summited Mount Everest. Twelve people have stood on the moon. Fewer than 10 people have thru-hiked the Grand Canyon.

And Holycross did it the year after his wife fell to her death there.

***

Matthias Kawski is a President’s Professor in Arizona State University’s School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences. He came to the university in 1987 because of Arizona’s canyons and mountains.

He backpacked the Grand Canyon the year he arrived, and the year after that. He was hooked.

“That was the reason I stayed,” Kawski said.

Holycross walked the south side in sections over a decade. Kawski was with him on most of those trips.

***

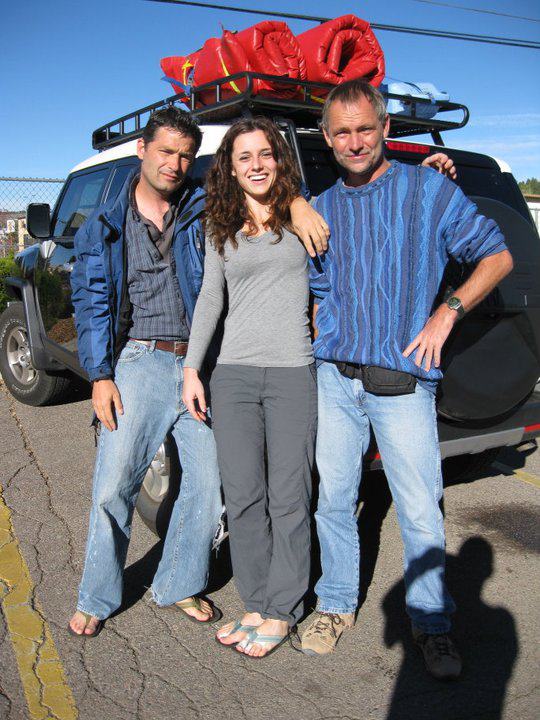

Ioana Hociota and Holycross, a herpetologist and adjunct professor in ASU’s School of Life Sciences, met in 2006. A Romanian immigrant, Hociota earned dual degrees from ASU in biology and mathematics. A year after they met, they went backpacking in the canyon.

She loved it. They returned, over and over.

Kawski had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2004. His doctor told him his goal had to be minimize immobility. The German math professor in love with wide open spaces was told he faced using a wheelchair, blindness and brain fatigue over the next five to 10 years.

“I was totally devastated,” Kawski said. “Ioana brought me back to life."

The trio did 12 serious, sustained, six- to 10-day trips together in freezing conditions in extremely remote parts of the canyon.

“You are up and down, up and down,” Kawski said. “You’re walking on whatever ledge is there until the walls come together and there is no more left. You either have to go 1,000 down or 1,000 feet up.”

Eventually they started looking at the map.

“We had these big gaps where we hadn’t hiked,” Holycross said. “It was like, ‘Hey, let’s put the pieces together.’ We started going in and knocking out the gaps.”

In 2010, Hociota convinced Kawski, then six years post-MS diagnosis, to come on an eight-day trip along the Sinyala fault in the western canyon. It’s a 17-mile-long fracture breaking through a cliff band.

Kawski told his neurologist.

“No way,” was the response. Way too dangerous. Tripping. Falling. Sudden paralysis. Probably a helicopter rescue.

“The turnaround of my life was the winter hike of the Sinyala fault in 2010,” Kawski said. “Ten years later (that neurologist) admits that the inspiration, commitment to such exploration and challenges likely have helped keep my (multiple sclerosis) under control.”

***

In June 2011, Holycross and Hociota were married on the rim.

The following winter, Hociota asked Kawski to join her in knocking out a section Holycross and another friend had already completed. It was a loop around the Great Thumb Mesa, a finger of land on a bend in the river in the western end of the canyon, next to the Havasupai reservation. The route was 16 miles. They planned to do it in three days. They would start Feb. 24 and hike out on Feb. 26.

When the terrain wasn’t too difficult, they followed different paths. When it was challenging, they stayed closely together. On the second day, Hociota contoured around a hill while Kawski chose to go over the top.

Kawski heard rocks tumble, then a sharp scream.

Hociota fell about 300 feet. No one knows exactly what happened. She was not a reckless hiker, according to Holycross. More than likely, it was just bad luck. A misstep on the wrong rock.

About 12 people die each year in the Grand Canyon. The tally to date is about 700, according to "Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon," the definitive work on the subject.

***

At the time of her death, Hociota had logged 830 miles in the canyon. She had 80 miles left to become the youngest person to complete a sectional thru-hike of the entire canyon.

“Before she fell, we had scheduled the last trip, and it was for March,” Holycross said. “She fell in February, on the 26th.”

Feb. 26, 2019, is the park’s centennial.

Ten days after her death, Holycross and Kawski went back to the canyon.

“That was a hard trip, but it was necessary to finish it because she had planned to be on that," Holycross said. "I carried her backpack and a lock of her hair so that she could complete it too.”

Why keep going back after her death?

“My first inclination when we got the news was a visceral hatred of the canyon because, in my mind, that’s what took her,” Holycross said. “But I realized that feeling doesn’t make sense; it’s not rational.

“That feeling didn’t last long. It was sort of a fleeting thing. Later, the more I thought about it, that was the place where Ioana and I were at our best. As a couple we were peas in a pod down there. She loved it there. In fact, there’s a saying in Romanian when you get married: ‘Casa de Piatră.’ House of Stone. We said that was the canyon for us.

"The canyon transcends all that, all of the horrors of our lives and everything else. It’s there and waiting for you. You accept it on its terms. Part of it is — what would she want? Would she want me to stop going there? Would she want Matt to stop going there? She would have kept going, I’m reasonably sure. She was passionate about the canyon, passionate about its conservation and wild places, passionate about challenging yourself more than anything else. … Why walk away from that?”

***

Then came the thru-hike.

“Before Ioana passed, we had decided we were going to do a thru-hike with a couple of friends,” Holycross said. “After she passed, I felt like I still needed to do that. Sixty-five days, Lees Ferry to Pearce Ferry.”

The park has four different types of trails. Corridor trails are the superhighways like Bright Angel and South Kaibab, where the mule trains travel and which rangers recommend to first-time visitors. Corridor trails are regularly maintained and patrolled, with water stations and other goodies. Threshold trails, like Hermit and Thunder River, are maintained when something is damaged by storms or floods. They’re regularly visited, but not by the hordes you see on Bright Angel. Primitive trails are far out there. You’re not likely to see anyone else. Nankoweap is the hairiest of the primitive trails, with some crazy exposure, meaning there’s a long way to fall.

Then there are wilderness routes. Triple black diamond. You won’t see another soul. These are footpaths or animal trails — at best. You’d better know what you’re doing, because you are out there. There are no trails along 95 percent of the North Rim or along 80 percent of the South Rim.

Being a great outdoorsman is not about being great at one thing. It’s about being great at 1,000 little things. How to stay warm. How to stay cool. How to read terrain, maps and ground for routes that “go.” Or don’t go. How to assess risk, judge it and execute it. Where people like Holycross and Kawski go, something as small as a broken bootlace can lead to your death 48 hours later. Make one mistake, and problems combine, compound and get worse.

“A lot of it is luck,” Holycross said. “There’s skill, but there’s luck too.”

When people do a sectional hike of the canyon, they go up on weekends and vacations and knock out sections. It can take people decades to complete. Only about 40 people have done it.

A thru-hike means you don’t come out of the canyon until it’s done. You don’t take breaks by taking a weekend off in a town, for instance. You might take a layover day where you stay in camp and repair gear and catch up on sleep, but you don’t leave.

“Staying down there, and not coming up … can be extremely difficult,” Holycross said. “The temptation to come out ... see the people you love … and simply take a warm shower and eat a steak … can be powerful. There is something to be said for resisting that temptation from ferry to ferry.”

When Holycross did his thru-hike on the north side, it was more than 500 miles. But because hiking Grand Canyon is almost never in a straight line, he estimates he walked close to 600 miles.

***

Holycross cached half of his supplies ahead of time, stored in five-gallon buckets hidden in the canyon. The remaining buckets were placed by friends from the river. “I had to find them,” he said. “That was nerve-wracking.” There were 11 buckets total.

He had custom topographic maps printed out — he doesn’t like GPS — and each section was stashed in his cache buckets.

“My training for Grand Canyon was to get as fat as I could,” he said. “Honestly. I knew I was going to lose weight. And I did. I lost 30-some-odd pounds in two months.”

What does two months of solitude do to your head?

“It gives it a different kind of scramble than this place does,” Holycross said, sitting in a Starbucks under a flight path and next to six lanes of rush-hour traffic.

“The thing that people find the most overwhelming about the canyon — and I’m talking about the places away from the trails, which is most of it — is not just how isolated you are, but how wild it is, and how frickin' quiet it is,” he said. “You get into this different head frame. All of this noise is gone, and all of the schedules and 'have-tos' and people asking for things — it’s all gone. Your body gets into this rhythm of sunrise and sunset. My most important concern of the day is ‘What’s my camp going to be like tonight?’ and ‘Is there going to be water there?’ You don’t really care about anything else.”

Find water. Find the route. Stay safe.

**

Kawski was way behind Hociota and Holycross when they expected to have section-hiked the length of the canyon on the south side in spring 2012.

“I never had any intention of doing the same,” he said. “But afterwards, I decided to do it — a tribute to Ioana, who helped me so much.”

So, eight years after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Kawski decided to hell with the disease, he was going to do it. At that time he had completed the Old Park and Monument, and a small section of Marble Canyon. Sixty miles of Marble Canyon remained — a very different landscape and challenge, consisting of steep slopes with little vegetation, narrow terraces on the east and south sides, and extreme bushwhacking on the final section along the river.

A year later, he completed his sectional thru-hike at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. Kawski is among the approximately 40 people who have completed this feat.

“I am still trying my best to fight MS — Ioana had a huge impact,” he said. “The Grand Canyon did, too. But I credit the inspiration, and the ultimate challenge to complete such amazing trips to my survival, the strength not to succumb to such an awful, incurable, so often debilitating, disease.”

***

Tragedy can transform. Hociota's example of honoring life by living it fully left an indelible mark. Holycross now is remarried to another remarkable and vibrant woman; the couple have two beautiful daughters. Kawski and Holycross remain the closest of friends and have continued to raft and hike the canyon over the past seven years.

Kawski and Holycross established the Ioana Elise Hociota!!! Memorial Mathematics Scholarship at ASU to honor her life. The scholarship helps support the educational dreams of immigrant women in mathematics. There have been seven recipients from seven countries to date.

Make donations to the scholarship to increase the number of recipients reached.

All photos courtesy of Andrew Holycross and Matthias Kawski.