Pull carbon out of the air, make money from it and save the human race.

Speeding up that process and creating a large-scale economic sea change was the topic of a panel hosted by Arizona State University on Thursday night at the Barrett & O'Connor Center in Washington, D.C.

A financier, a businessman, a policy expert and the inventor of a carbon-capture machine discussed the opportunities and obstacles involved in turning waste into capital at “Hacking for Carbon: Building an Innovation Pipeline for the New Carbon Economy.”

Their panel was part of a workshop, the goal of which was to consider how government, philanthropy and private capital can fund and de-risk a pipeline to create new technologies for the energy transition from hydrocarbons to renewable energy like solar and wind power.

Klaus Lackner has been thinking about how to manage carbon since the 1990s.

A physicist and environmental engineer at ASU, where he is the director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions, Lackner has built a machine that pulls carbon from the air.

“There’s no practical way to stop this in time,” Lackner said, referring to the predicted global rise in temperature. “We have to take it back. … We have to think about these technological fixes.”

Lackner pointed out the planet is beyond being repaired by planting trees, for instance. The problem is simply too huge.

“It is more challenging than most people think,” he said. “If you start getting serious about it, you see how big these numbers are. … What do we do with 17 tons of anything? The problem is fantastically large.”

However, he said, “the markets can figure this out.”

The money people at the table offered plenty of pathways toward creating a new market for carbon.

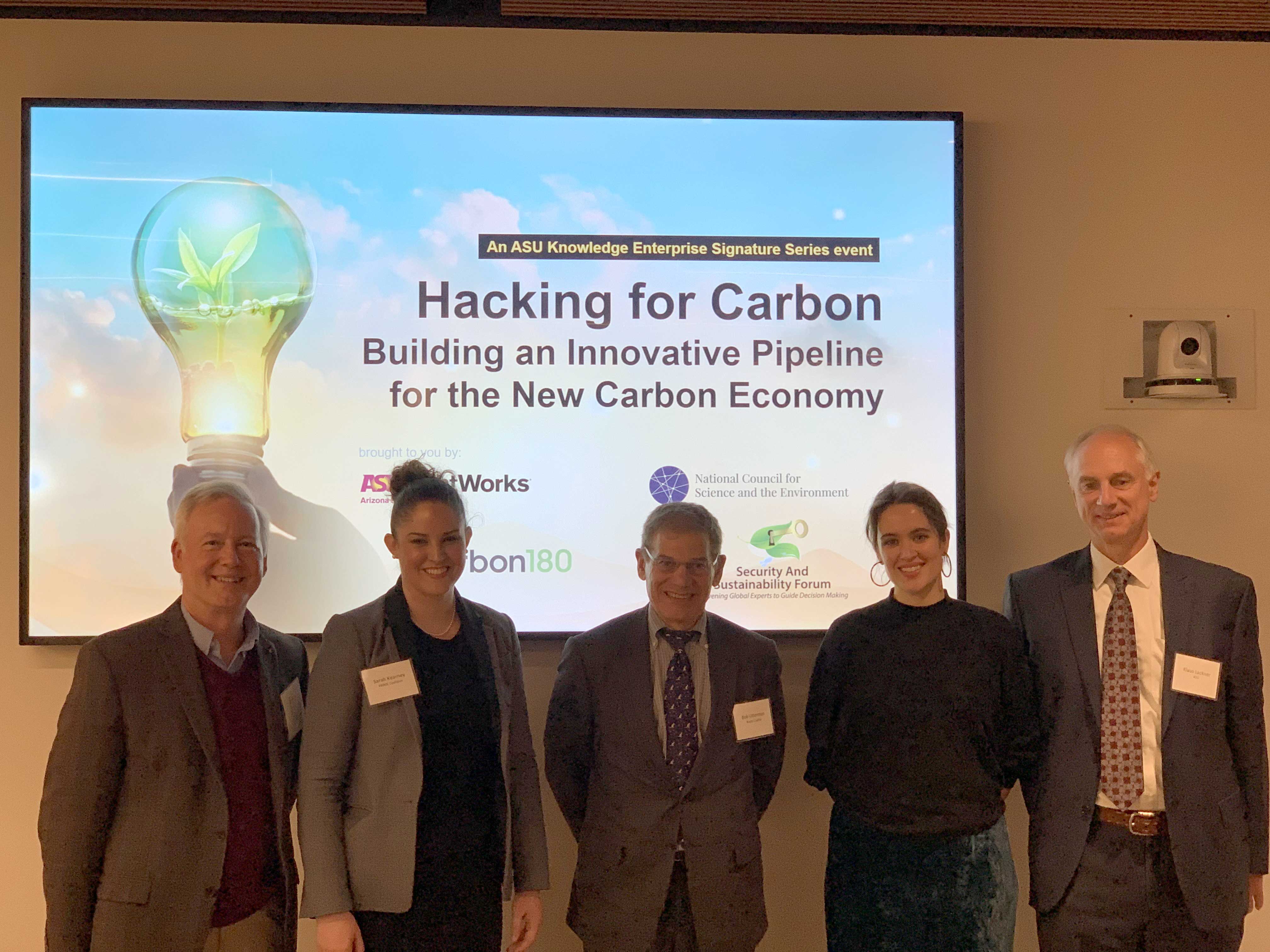

(From left) Tony Michaels, CEO of Midwestern BioAg; Sarah Kearney, founder of Prime Coalition; Bob Litterman, the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability board director; Erin Burns, associate director of policy at Carbon180; and Klaus Lackner, director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at ASU, spoke at the “Hacking for Carbon” event at the ASU Barrett & O’Connor Center in Washington, D.C., on Thursday. Photo by William Brandt/LightWorks

For accelerating and bringing new tech like Lackner’s to scale, “the easiest case should be, ‘You’re going to make a lot of money doing something different,’” said Tony Michaels, the chief executive officer of Midwestern BioAg, a sustainable agriculture company that sells carbon-based fertilizer blends, livestock nutrients, seed and specialty crops. “What do you have to change about the fundamental business model?”

“What are those barriers, and what do you have to do to overcome those barriers?” said Michaels. “Don’t start with the innovation; start with the profit. … Get the creativity working on that.”

The goal is to help clean-tech companies become attractive to investors, said Sarah Kearney, the founder of Prime Coalition, a nonprofit that partners with philanthropists to invest charitable capital in companies that combat climate change, have a high likelihood of achieving commercial success and would otherwise have a difficult time raising sufficient financial support.

Kearney said a balance of philanthropic and fiduciary capital for initial investment into clean tech is the key to success.

“You want companies to graduate from needing the charitable support,” she said. “The risk is a scarlet letter. … Once you get a lot of the big-name reputable organizations, all of a sudden it becomes a club you want to be a part of.”

In the three quarters after the 2015 Paris climate talks, there was no investment in clean tech reported at all, Kearney said.

Policy needs to work in tandem with finance to get the private sector ready to take advantage of clean-tech markets, said Erin Burns, associate director of policy at Carbon180, a climate-focused nonprofit pushing technology that captures carbon-dioxide emissions and working to support its commercialization.

“We think the most pressing need is for a robust (research and development) program,” Burns said. “Right now, what we’re spending isn’t really enough.”

“Today I’d say we’re at square one, maybe square two,” Burns said. “How do we build the kind of ecosystem that allows these projects to be built at scale? … What are the policies we need to work through now? … Maybe it’s naïve, but we’re really optimistic.”

Can the damage be minimized?

“There’s a big difference between waiting 30 years and starting today,” Lackner said.

The discussion was hosted by Arizona State University’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability in partnership with the National Council on Science and the Environment, the Security and Sustainability Forum and Carbon180.

Top photo: The direct-air carbon-capture machine at ASU's Polytechnic campus, a project of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions. Photo by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

More Environment and sustainability

Planting for the future: ASU helps elementary students design cooler Phoenix schools

On a cool Phoenix morning, dozens of young students from the Phoenix International Academy clustered around freshly dug holes, gripping shovels and saplings nearly as tall as they were.Within a…

Phosphate powers life as we know it; yet most of us flush it down the drain

Elemental phosphorus is too volatile to exist in nature.Expose a pure sample to air, and it could easily burst into flames. But connect a few oxygen atoms in water, and phosphorus becomes phosphate,…

Will rapid data center growth help Arizona? Examining the pros and cons

Arizona is engaged in a debate about where data centers should be built — with cities, developers and residents having varying opinions on the issue.So how do we find common ground?That was the…