Students reimagine ASU campus with designs that better reflect Native cultures

Arizona State University has more than 3,000 Native American students, and a group of them has created a powerful proposal to redesign the campus to reflect their culture. The ideas include adding pottery symbols to Sun Devil Stadium, building a “welcome wall” to include the languages of the 22 tribes in Arizona, and building a storytelling pavilion and gathering place.

The concepts came from six Native American students who took a studio course last year with Wanda Dalla Costa, Institute Professor in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts. Dalla Costa said that when she came to ASU three years ago to teach construction management, she didn’t see any Native American representation.

“To be honest, I looked around and said, ‘Where are the historical markers of the people who lived in this place?’ I could only see them when I drive on the highways,” she said.

So the students worked on ways to use design to bring representation to the campus and came up with 16 proposals. Their work, and Dalla Costa’s ethic of “design sovereignty,” has been gathered into a new book, titled “Indigenous Placekeeping: Campus Design + Planning.”

Dalla Costa, a member of the Saddle Lake First Nation in Alberta, Canada, and the first First Nations woman to become an architect in Canada, believes that local communities should control the design practice.

“The community has to drive the priorities, and they should also drive the process,” she said.

Dalla Costa and the students held a design workshop on Tuesday evening to unveil the new book and to engage the community in their ideas. The event was part of Native American Heritage Month, co-sponsored by ASU Alliance of Indigenous Peoples and the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. The original studio course was sponsored by the Office of the President and the Office of American Indian Initiatives.

From left: Brian Skeet, Rhonda Harvey, Institute Professor Wanda Dalla Costa, Lauren Slim and Selina Martinez stand with their book, "Indigenous Placekeeping: Campus Design + Planning" during a design workshop held Tuesday to unveil the new book and to engage the community in their ideas. Photo by Marcus Chormicle/ASU Now

Several of the students’ designs incorporated imagery of the map of canals created by the Hohokam Indians, which led to the creation of Phoenix. The map is on the cover of the book as well.

“This is the most important aspect of the city. The canals still exist,” Dalla Costa said.

“The Hohokam people used sticks to dig canals to bring water. They are the original placemakers.”

Among the 16 projects is an idea by architecture student Selina Martinez, a Pascua Yaqui tribe member, to embed the canal map in the glass façade of the Arizona Room in Hayden Library, which is currently being renovated.

Other concepts by the class included having Native artists paint murals on campus, adding multi-lingual signage using local indigenous languages and transforming existing walkways into interpretive artworks.

Lauren Slim, a landscape architecture graduate student, proposed a “welcome wall,” which would include a phrase of welcome from each of the 22 tribes in Arizona.

“It’s super simple and super feasible,” said Slim, who is Navajo.

Brian Skeet, a Navajo student who is majoring in industrial design, proposed a multi-level structure based on the traditional maze design. Each level would be dedicated to a different activity, including congregation, rejuvenation and celebration.

“This is basically where people can come and feel like they’re at home,” he said.

“It’s inspired by the maze because it’s about your journey through life. With each level, you’re going through different phases of life.”

Rhonda Harvey, a graduate student in urban planning and architecture, proposed a storytelling pavilion gathering space, which would look like a basket and from above would look like a rug.

“It’s inspired by Navajo rug weaving, which is one of the ways tribes tell stories,” said Harvey, who is Navajo.

“I wanted to do an outside space to emphasize the relationship with nature and keep it grounded.”

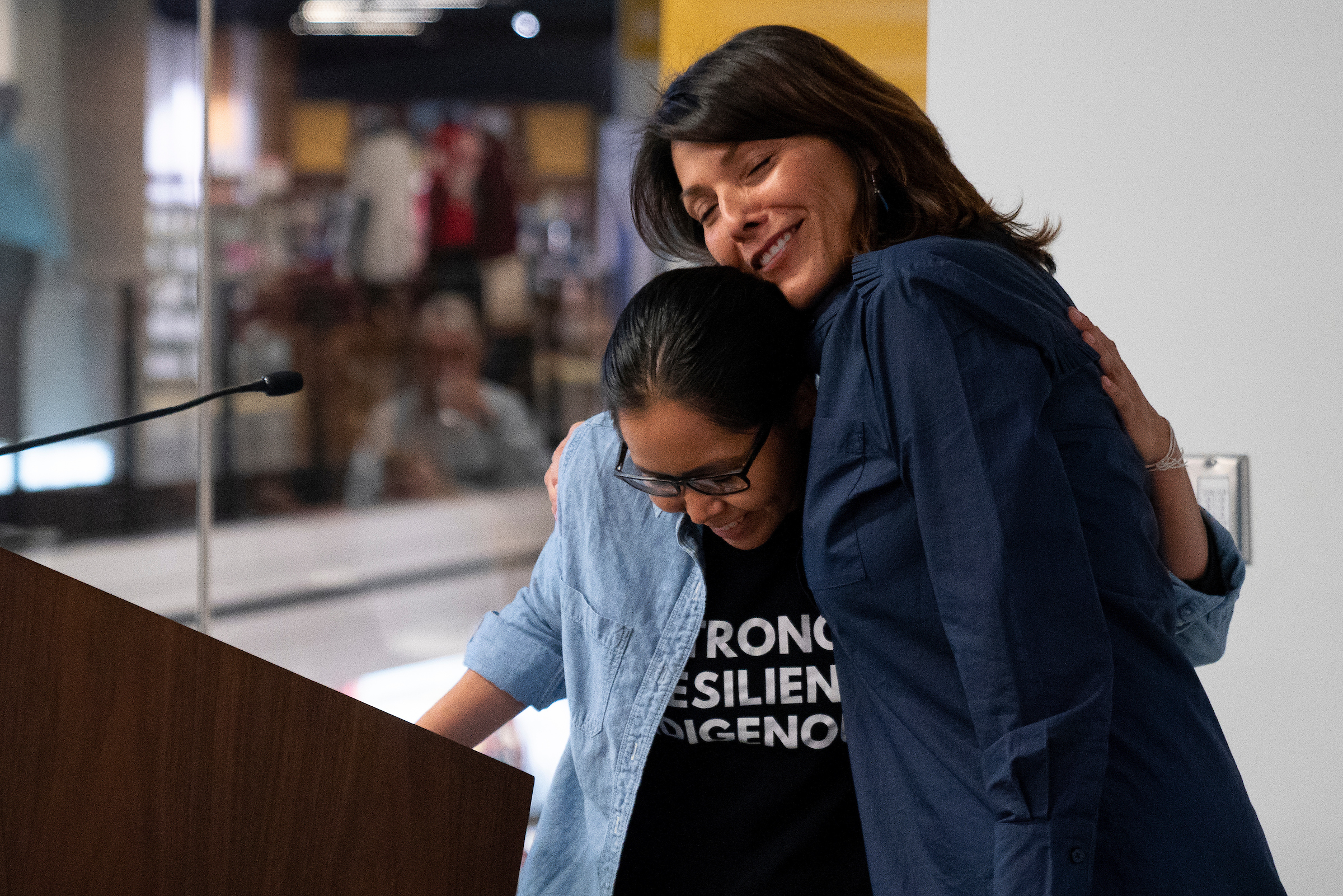

Rhonda Harvey, an ASU graduate student studying architecture and urban planning, gives a teary-eyed hug to Professor Wanda Dalla Costa at the "Indigenous Placekeeping" event Tuesday in Tempe. Photo by Marcus Chormicle/ASU Now

Not all of the proposals were visual. Ravenna Curley, an industrial design student and Navajo, reworked ASU’s design aspirations into “Indigenizing ASU’s Design Aspirations,” to be used to rework degree programs and coursework to incorporate indigenous cultures.

“I had a hard time finding my place at ASU. It was a whole culture shock coming from the rez,” she said.

For example, the design aspiration “leveraging our place” becomes “Acknowledging local people of this land and recognizing that this campus is on indigenous lands included on all course syllabi.”

“This is Native land,” Curley said, “and we don’t acknowledge it anywhere on campus, and that’s kind of sad.”

To buy a hard copy or online version of “Indigenous Placekeeping: Campus Design + Planning,” contact Dalla Costa at [email protected].

Top photo: Selina Martinez, an ASU graduate student studying architecture, speaks Tuesday evening about her design for creating a more inclusive space for indigenous students on the ASU Tempe campus. Photo by Marcus Chormicle/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU course explores culture through an interdisciplinary lens

When Razieh Araghi joined Arizona State University in fall 2025, she wanted to show students the power of humanities. Her course — SLC 202 Exploring Cultures: Words, Images, Stories — aims to do…

ASU launches ‘AI-Informed Writing Classroom’

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”This question, attributed to novelist E.M. Forster, alludes to the role of writing in discovery and cognition.In 2026, the existence of large-…

Fluent Futures Lab teaches what English textbooks miss

Learning English is about more than mastering key vocabulary and demonstrating verb tenses — it’s about knowing what to say, how to say it and when. At Arizona State University,…