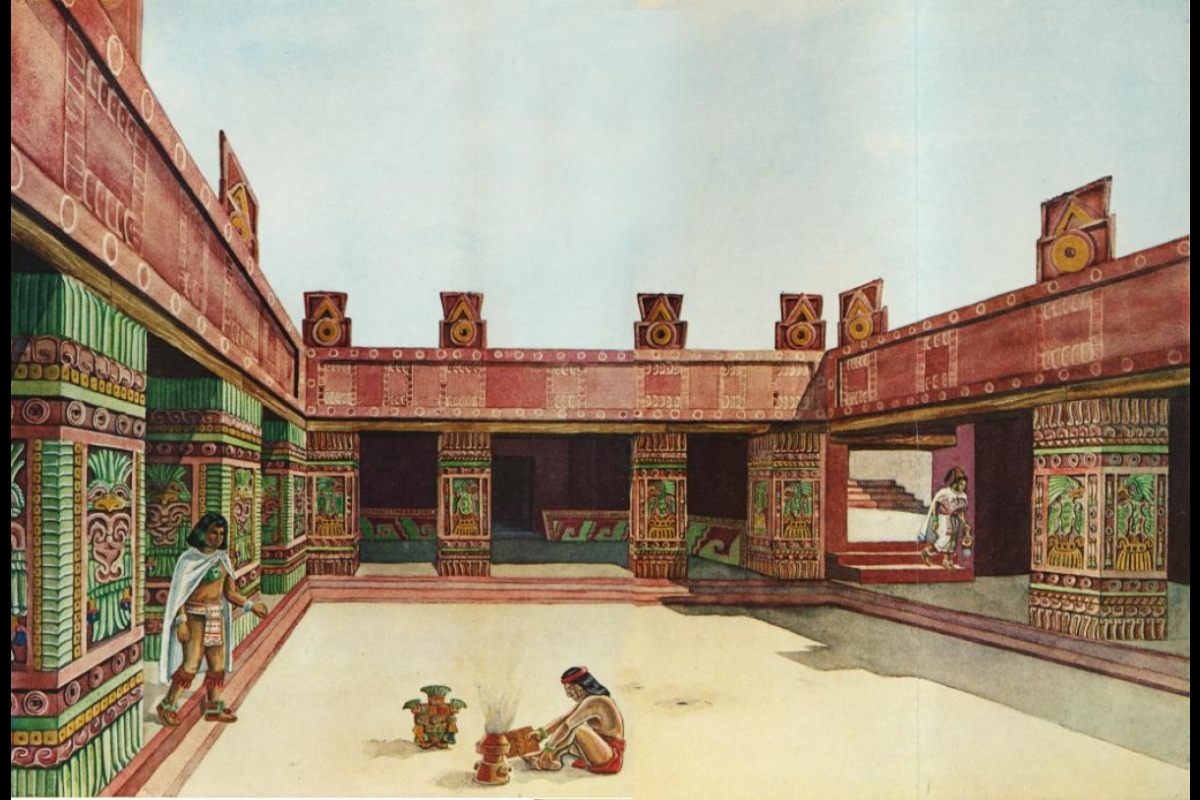

Imagine a renaissance city where revolutionary ideas in urban planning, politics, economy, ecology and the arts all arose at the same time, creating a high standard of living that was largely equitable for nearly all residents.

It’s hard to imagine even by today’s standards, yet one ancient Mesoamerican city seemed to have achieved that status, for a time, and the archaeological remnants from that period and location are available for research and discovery today.

Teotihuacan is a famed UNESCO World Heritage site located in central Mexico that receives 2 million visitors each year. Yet few of these countless visitors throughout the decades have given back as much as one — a man by the name of George L. Cowgill.

The late archaeologist and professor emeritus at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change died this summer after spending much of his lifetime studying and preserving the majesty of Teotihuacan.

“George’s dry humor often enlivened his professional and personal interactions,” remembered ASU Professor Emeritus Barbara Stark, “as did his wide knowledge of research on ancient civilizations.”

Over decades, Cowgill proved himself an invaluable ally and friend of Teotihuacan with regards to the global scientific community, the Mexican government and peoples — who allowed him and other researchers access to their history, resources and communities — and countless students, supporters and members of the public, whose interest only grew with each new discovery.

In 2018, this legacy continued with a posthumous $1 million donation to ASU made by his family to help honor this lifelong commitment and create further opportunities for worldwide scientific and cultural access and appreciation of the site.

Falling under Teo's spell

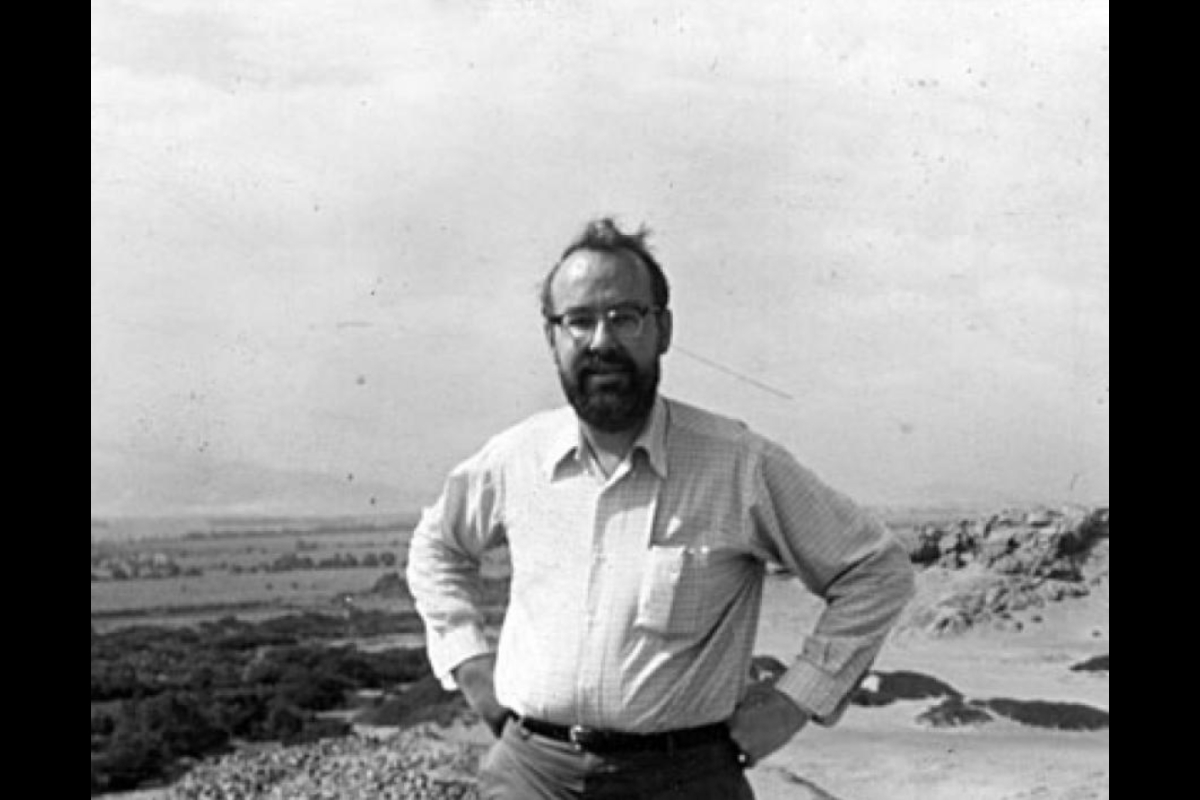

Cowgill began the Teotihuacan portion of his career in 1964 under the invitation of famed researcher René Millon, who was looking for help with an ambitious project to map the scope of the city in its entirety.

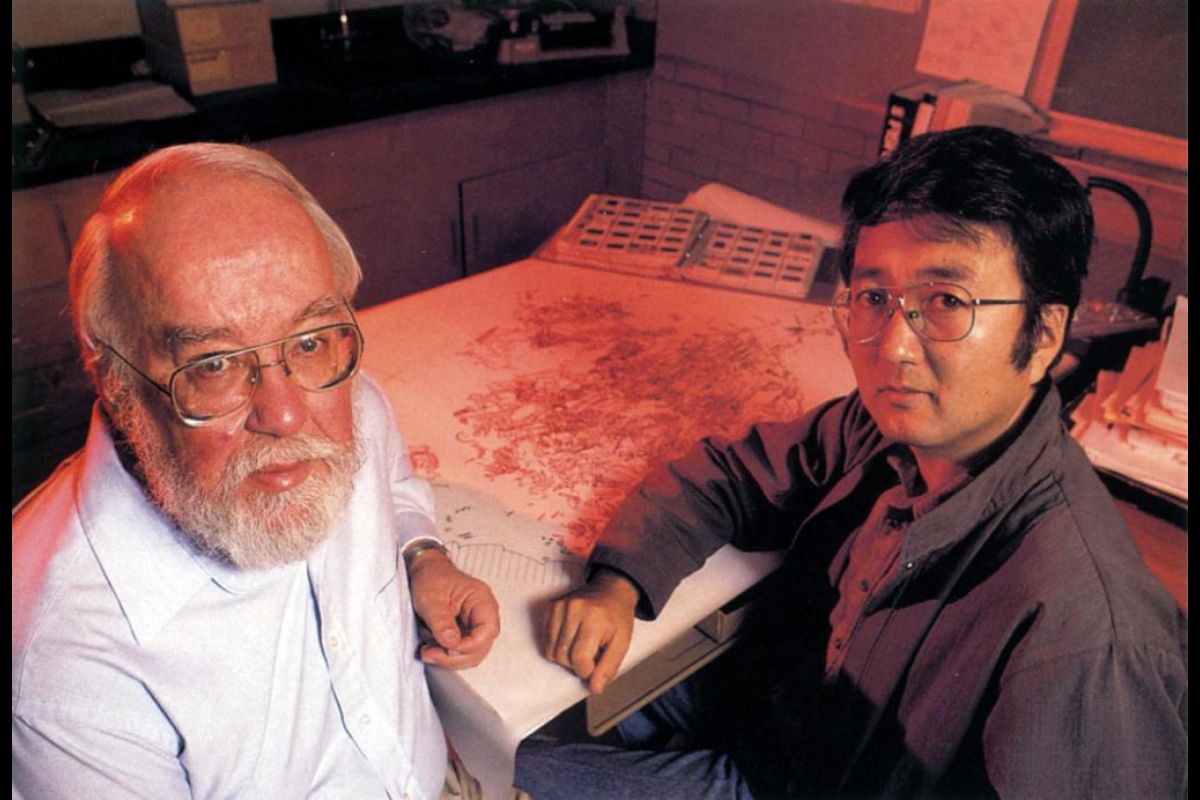

Famed anthropologists and Teotihuacan Mapping Project colleagues René Millon (left) and George Cowgill.

Other major efforts by Cowgill spanned decades, including an excavation alongside ASU Research Professor Saburo Sugiyama at the site’s Feathered Serpent pyramid, and the development of a database — one of the field’s largest at the time — of Teotihuacan surface artifacts. Along the way, he pioneered several novel enhancements to quantitative methods in the industry’s scientific tool kit, in areas such as chronological seriation, artifact classification and spatial analysis.

In addition, he was a co-founder of the first externally owned research lab onsite, the Teotihuacan Research Laboratory, and strategically grew its resources, infrastructure and influence over nearly three decades as its director.

Today, as an ASU-owned facility managed by the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, the lab continues to serve as a main base camp for scientific discovery, including use by researchers and visiting anthropology students from the United States, Mexico and the rest of the world. It also houses thousands of boxes containing the roughly 1 million artifacts and samples recovered from the site to date.

“George ran the lab as an incubator of ideas to be tested in field projects by scholars of different perspectives and nationalities, and thought that all artifacts, whether common or rare, mundane or exquisite, deserved careful study and fierce protection,” ASU Professor Ben Nelson said.

Over the course of his career, Cowgill authored more than 130 professional publications, and his 2015 book “Ancient Teotihuacan” is considered the definitive general work on the city.

In 2004, he and Millon were also jointly awarded the Alfred Vincent Kidder Award for Eminence in the Field of American Archaeology by the American Anthropological Association.

Despite Cowgill’s and others’ exhaustive efforts, current estimates are that only a paltry 5 percent of the total area that is Teotihuacan has been excavated and analyzed. The other 95 percent still remains buried.

Lessons from the past and a future that endures

The Aztecs did not build Teotihuacan, but it was they who named it a “city of the gods.” And Cowgill’s findings over the decades consistently reveal a culture that was — at its peak — certainly worthy of such a grand title.

For example, it boasted extensive trade networks and marketplaces, and also influenced far more regions through its culture — including ritual programs, specialized crafts and a political prestige; things that other societies envied and emulated — than it absorbed through force.

“George’s willingness to seek answers to the future from lessons of our past has since proved prescient,” explained Michael E. Smith, the current director of the Teotihuacan Research Laboratory and a student of Cowgill’s at Brandeis University in the 1970s. “In a world where our ability to simply ‘spread out’ as a solution for population growth is rapidly diminishing, these lessons from the past may be key in creating safer, fairer and more effective cityscapes of tomorrow.”

As Cowgill himself explained in a 2013 interview, “We shouldn’t think of past cultures as disappeared. They have a continued life in another form. They remain relevant.”

That’s not to say life at Teotihuacan was always idyllic — in fact, Cowgill was involved with the discovery of the first pyramid at Teotihuacan associated with ritual human sacrifice. And despite hundreds of years of evident prosperity, the city also met a comparatively swift decline and abandonment in its final years, culminating in the burning of its civic center in A.D. 650.

However, one of Cowgill’s greatest insights was never to let sensational or surface-level assumptions take away from the big idea of Teotihuacan — that even in a place of this magnitude, everyone matters and deserves to have their story told.

“The great pyramids, the haunts of rulers and high priests, are important, but the dwellings of ordinary folk are also vital for understanding a complex urban society,” he said in 2011.

A democratic and egalitarian idea, as manifest in the man as in the city he studied.

Throughout his life, “George brought people together, whether through the scientific conferences hosted in his name and or by lending his extraordinary knowledge to museum displays and public learning opportunities,” said President’s Professor Kaye Reed, director of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

Now, this gift in honor of his memory will enable Cowgill’s major physical legacy — the ASU Teotihuacan Research Laboratory — to continue and enhance its core missions.

Local and international students, scientists and others will continue to learn about and preserve the past of Teotihuacan through research and curation, and new approaches to in-person and online outreach, education and scholarship will be developed, Smith said.

“This donation is an incredible legacy and will be invaluable to keep the discoveries coming at Teotihuacan for generations to come.”

Top photo of Teotihuacan by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU's Pen Project helps unlock writing talent for inmates

It’s a typical Monday afternoon and Lance Graham is on his way to the Arizona State Prison in Goodyear.It’s a familiar scene. Graham has been in prison before.“I feel comfortable in prison because of…

Phoenix civil rights activists highlighted in ASU professor’s latest book

As Phoenix began to grow following WWII, residents from other parts of the country moving to the area often brought with them Jim Crow practices. Racism in the Valley abounded, and one family at…

Happy mistake: Computer error brings ASU Online, on-campus students together to break new ground in research

Every Thursday, a large group of students gathers in the Teotihuacan Research Laboratory (TeoLab) in the basement of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change building on Arizona…