If academic units had patron saints, the Arizona State University English department’s would be Geoffrey Chaucer. In recognition of his lasting influence on the field, every couple of years the department sets aside a day in the spring semester to honor the man known as the father of English literature.

This year, the sixth biennial event, the ASU Chaucer Celebration: Twenty-First-Century Chaucer, will take place Friday, March 23 at various locations on the Tempe campus in the hope of (re)introducing the author to contemporary audiences. The daylong series of events include readings, viewings of early printed editions of Chaucer texts and a dramatic re-enactment of an updated version of “The Canterbury Tales” starring ASU students and faculty.

The day kicks off at 9 a.m. at Old Main, where U.K. poet Patience Agbabi and young adult author Kim Zarins will read from their respective works, “Telling Tales” and “Sometimes We Tell the Truth,” both of which were heavily influenced by “The Canterbury Tales.”

The authors shared their passion for Chaucer with ASU Now, delving into the secret behind his lasting appeal, who they consider to be modern-day versions of him and advice for approaching — or re-approaching — his work.

Editor’s Note: Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

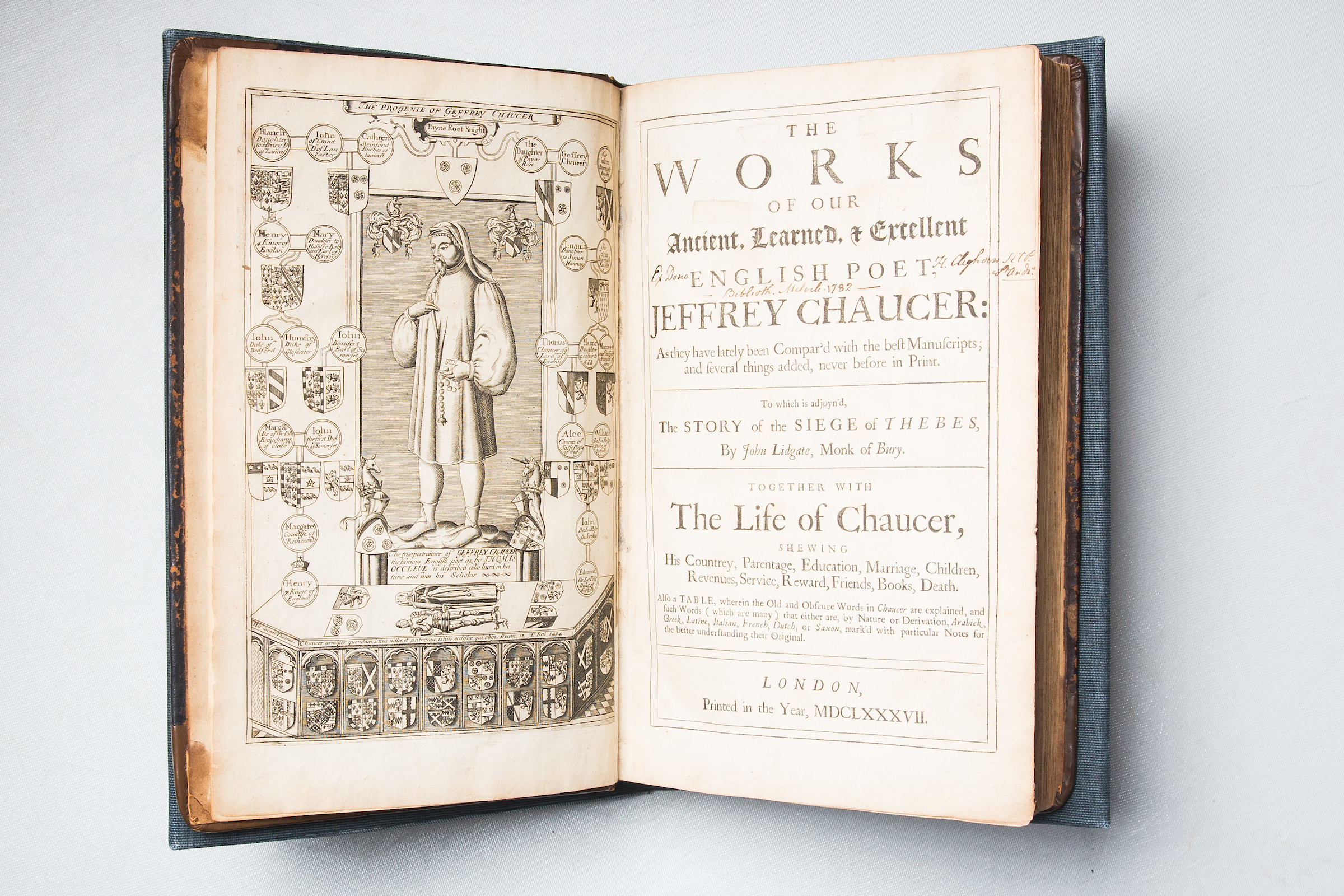

"The Works of Our Ancient, Learned, & Excellent English Poet. Jeffrey Chaucer," circa 1687 on display at the Hayden Public Library at Tempe campus Thursday morning on Sept. 22, 2016. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Question: What is it about Chaucer’s work that allows it to appeal to many readers, over many generations?

Patience Agbabi: I’ve read the majority of Chaucer’s work but it’s "The Canterbury Tales" I’ve revisited the most and what I’d call his masterpiece. It has longevity because he rewrites those timeless stories circulating Medieval Europe in the voices of unique, three-dimensional characters that leap off the page. The best stories use the vernacular and although the English language has changed much since then and "The Canterbury Tales" may be more challenging for a modern reader, the energy of the language connects.

Kim Zarins: It’s funny! Funny in a wild, raunchy, slapstick way. And it’s just big. Chaucer’s "Canterbury Tales" has what Dryden called “God’s plenty.” There’s just so much — such vibrant and diverse characters, such silly shenanigans, and then such a range of feels, with some tales that make you snort and others that disturb the heck out of you (sometimes all in the exact same tale, just moment to moment).

Agbabi: The power of humor in great literature is not to be underestimated. Chaucer’s humor works on several levels from the irony to linguistic play to below-the-belt. Our laugher, our visceral response, connects us intimately with the text and enables us to remember it on a physiological as well as intellectual level.

Q: Chaucer’s inclusion of a wide range of classes and types of people in “The Canterbury Tales” gives us some insight into society at that time. Were either of you hoping to provide some insight into contemporary society with your updated versions?

Zarins: Yes. What I especially wanted to get across is that it’s easy to typecast people: jocks and nerds, loners and stoners, moochers and future frat boys. But each of the characters on this road trip have deeper interiorities and a tale of their own to tell. The characters on the bus start to perceive that, even though they all largely stay in their own social groups. It was intriguing to explore those groups and all the passionate awkwardness that is high school. Plus, it’s super fun turning all of Chaucer’s characters into teenagers, giving them acne and cell phones and all those painfully fierce desires.

Agbabi: I didn’t have a specific agenda. I was aware I was representing a contemporary Britain that was multicultural; I deliberately made 50 percent of the tellers women to redress the gender balance. I tried to represent a range of ages and classes as Chaucer did. But the primary impetus behind the work was to investigate Chaucer’s medieval English, represent his vernacular by using contemporary slang in several of the pieces and celebrate his prosody. In that way, my project was more navel-gazing than social. Yet due to my upfront, giving-voice-to-the-voiceless poetic aesthetics, several of the tales give insight into all kinds of contemporary issues: racism, poverty, street violence. It was impossible to take Chaucer into the 21st century and not be affected by the contemporary world. By privileging the vernacular as Chaucer did, I was, in effect, echoing and mirroring society.

Q: If you had to compare Chaucer to a contemporary writer or artist, who would it be and why?

Agbabi: It would have to be someone who married high art with popular culture, steeped in the classics but relishing the vernacular. Someone who understood that a poem should not only exist on the page but in the air. Someone with a marked facility with language, an enormous range of registers. That someone is Kate Tempest. She combines the lyricism of hip hop and the Greek chorus. Her gods are alcoholics, her soothsayers are vagrants, her language is alive on the page and performed totally from memory on the stage. For this reason, she appeals to a broad audience and her work will have a long shelf life, literally and metaphorically.

Zarins: I’m going to go with Terry Pratchett. Both [Chaucer and Pratchett] make you laugh out loud, plus both are razor-sharp satirists with a keen radar for hypocrisy in society. They both use stock characters who nonetheless become real people as muddled and contradictory as the rest of us, yet the stock element is still there, which makes me think there can be stock qualities to ourselves, but that doesn’t make us any less real. Chaucer and Pratchett are shockingly brilliant, yet down-to-earth enough (or down-to-Discworld enough) that they are always open to slapstick and cheesy puns, which I’m a sucker for. Both tickle your brain but then tug on your heart. I pay my deep respects to Pratchett and his character Death when I retell the Pardoner’s Tale, which I’d done on intuition without thinking about it further, and now I’m really glad I put the two authors together. They would have been great friends.

David Rachor (left) and Stefan Dollak of Bartholomew Faire, perform at the fifth biennial Chaucer Celebration on March 18, 2016. Dollak is playing the hurdy gurdy, as Rachor performs on the bladder pipe. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Q: Why is it important to not ignore the work of writers and artists from the past?

Zarins: If writers and artists only concern themselves with the present, art becomes myopic, and ultimately, the present can’t make sense or survive without the past, because the past isn’t just contextual window-dressing for the present. It’s the DNA that still informs the shapes we take and how we breathe and dance and dream.

Agbabi: If you love reading, you cannot limit yourself to one author, one genre, one century. You’ll be missing out on a whole tradition. All writers are a product of previous works. To be a writer, you first must read. You cannot write in a vacuum. You must read as many works from the past as you can and engage with other art forms that inspire. Good writing is timeless. It deals with every aspect of the human condition whether it was written in 1000 or 2000 A.D. That’s why good stories repeat themselves in different guises over the centuries.

Q: What would you tell readers who might be unsure how to approach Chaucer?

Zarins: Don’t let a disappointing first exposure ruin the past for you. Chaucer can be awesomely fun and deeply resonant. Sometimes when people put authors on a pedestal called The Canon, that fun and deep-down truth element can get lost. Give art a second chance every now and again. See if you’re ready for it. Sometimes with art it’s not love at first sight, but so worth it in the end. I promise.

Agbabi: At the end of "The Canterbury Tales," Chaucer addresses all those who "herkne" or "rede" his text. When you read Chaucer, don’t just read it on the page. Listen to it. Don’t just listen to it, voice it. Inhabit it. Do not confine this to Chaucer. Literature was around long before books. Reading books is one magnificent way to experience literature, especially in the academy, but it’s not the only way. We all know this. Let’s practice it.

The sixth biennial ASU Chaucer Celebration is sponsored by ASU's Dean of Humanities, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies; Department of English and its creative writing program; Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing; Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts and its School of Film, Dance and Theatre; Institute for Humanities Research; and Maxine and Jonathan Marshall Chair in Modern and Contemporary Poetry. For further information, contact the Department of English, 480-965-3168 or organizer Professor Richard Newhauser, Department of English, 480-965-8139 or Richard.Newhauser@asu.edu

Top photo: Shannon Phelps takes on the role of Zenobiz from "The Monk's Tale" at the fifth biennial Chaucer Celebration to commemorate the life and work of the medieval author on Friday, March 18, 2016 in Tempe. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

A humanities link from Harvard to ASU

Jeffrey Wilson didn’t specifically seek out Arizona State University professors when it came to filling out the advisory board for his new journal Public Humanities.“It just turns out that the type…

ASU professor’s award-winning book allows her to launch scholarship for children of female shrimp traders in Mexico

When Arizona State University Associate Professor Maria Cruz-Torres set out to conduct the fieldwork for her third book, "Pink Gold," more than 16 years ago, she didn’t count on having major surgery…

Herberger Institute Professor Liz Lerman to be honored as Dance Magazine Award winner

Dance Magazine has announced that Arizona State University Herberger Institute Professor Liz Lerman will be honored as a Dance Magazine Award winner at a ceremony Dec. 2 in New York City.“I…