The unexpected success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway hit “Hamilton” went a long way to rekindle Americans’ interest in the story of our nation’s founders.

At the center of the musical was the legendary rivalry between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Their volatile relationship and the wider drama surrounding America’s founding served as the basis of a lively discussion Wednesday night at ASU Gammage in Tempe.

The audience was welcomed by Paul Carrese, professor and director of Arizona State University’s School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership (SCETL), who promised the topics discussed would “reveal how the controversies and drama of our founding era” — such as vitriolic rhetoric, issues of truth in the press and questionable dealings with foreign powers— are still relevant to politics today.

Related: Paul Carrese on civility, in 60 seconds

The panel included SCETL Professor of Practice and noted Hamilton scholar Peter McNamara and Nancy Isenberg, author of “Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr” and the T. Harry Williams Professor in American History at Louisiana State University.

Though they differed on certain points, there was one thing the pair whole-heartedly agreed on: There are many misconceptions in our modern-day understanding of Hamilton and Burr as individuals, as well as their relationship.

Hamilton, thanks in large part to the craze created by the musical, is nowadays often revered as an infallible hero. But in his time, he was known for being controversial, prickly and even vain.

His popularity waxed and waned after his death, rising after the Civil War because of his emphasis on support of manufacturers and the union, and falling when FDR (who favored fellow Founding Father Thomas Jefferson) came to power. In the 1970s and '80s, Jefferson fell out of favor due to race issues, and Hamilton was back on the uptick, with Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography and Miranda’s soon-to-follow Broadway show solidifying his position in current popular culture.

“Hamilton has had a roller-coaster experience with his reputation,” McNamara said.

Burr, on the other hand, maintained a more steady public awareness, albeit not without its inaccuracies. Part of the reason for that is there has been much more fiction than fact written about him, with claims that he lacked character or was somehow less noble or moral than his contemporaries resulting in him being relegated to the role of the “American Judas” or “bad boy” of the founders, Isenberg said.

“To rely on Hamilton’s opinion of Burr is like relying on Ken Starr’s opinion of Clinton,” she said, when in actuality, Burr was a feminist who fought for the rights of immigrants, worked to reform voting rights at the state level and advocated for more transparency in the Senate.

Burr also “introduced a series of innovations we now take as givens,” Isenberg said. He collected data on voters and their issues of concern, he went to polls and gave speeches and, most importantly, he wrote the charter for the earliest predecessor of JPMorgan Chase, insisting it provide loans to lower-income citizens.

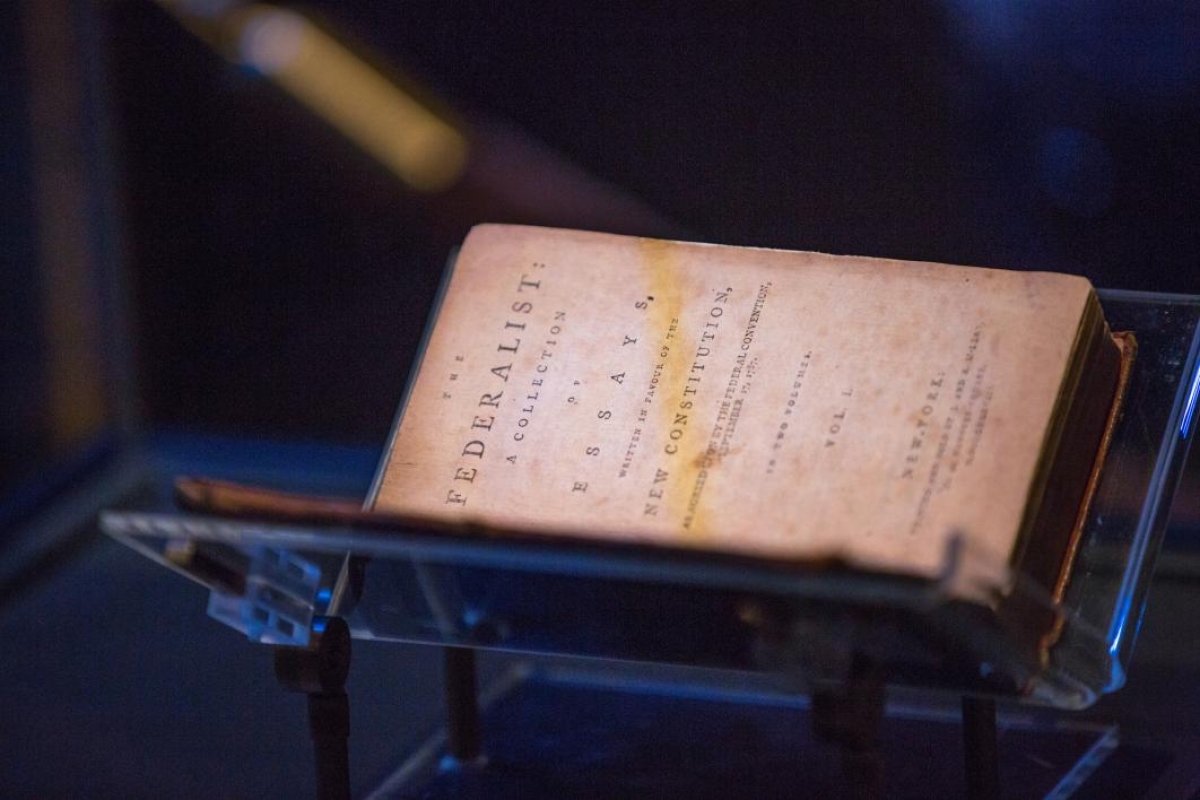

Hamilton also left behind institutions that are still here today and still work, McNamara said, including Bank of New York, the Coast Guard and the U.S. Treasury. Not to be forgotten are his numerous writings, including “The Federalist,” a first edition of which ASU has acquired and which attendees at Wednesday night’s discussion were able to observe on display.

And the famous duel? Also riddled with historical inaccuracies.

There are several outlandish theories as to what could possibly prompt two well-respected and educated figures to come to arms — including one in which Hamilton was rumored to have had a sexual desire for Burr, resorting to the duel as a death wish — but it’s really quite simple:

“Dueling was a common aristocratic practice back then in Europe and in the military,” Isenberg said. In America, it was a way to defend your reputation and move up the pecking order “in a world where one’s class identity was not as secure as in Europe.”

There are also rumors about whether Hamilton meant to throw away his shot, or even did return fire.

“Who knows [what really happened]?” McNamara said. Any way you look at it, it was unfortunate.

“They clashed and clashed and clashed,” he said. “[They both] said they liked each other, but what drove them apart was politics. And it was a real mistake on Burr’s part to shoot Hamilton … for more than one reason.”

As for the accuracy of Miranda’s “Hamilton,” Isenberg and McNamara feel that despite some historical inaccuracies, it did a great job of capturing the feel and emotion of the events it portrays. However, Isenberg cautions against the temptation to put any historical figure on a pedestal.

It may make us feel good about the past, but it doesn’t really engage the true history, she said. And though we may feel the urge to make our Founding Fathers into demigods who represent all that is good about America because they embody our origin story, we would do better to try to understand them in the context of their time; not as role models or geniuses, but as men who had to make difficult decisions to solve problems.

“If we understand that,” Isenberg said, “we can better understand the problems we face today.”

Top photo: Author Nancy Isenberg and ASU Professor of Practice Peter McNamara discuss Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton on Wednesday evening at ASU Gammage. Isenberg is the author of "Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr," and McNamara is part of ASU's School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership, who specializes in the history of Alexander Hamilton. Photo by Anya Magnuson/ASU

More Law, journalism and politics

How to watch an election

Every election night, adrenaline pumps through newsrooms across the country as journalists take the pulse of democracy. We gathered three veteran reporters — each of them faculty at the Walter…

Law experts, students gather to celebrate ASU Indian Legal Program

Although she's achieved much in Washington, D.C., Mikaela Bledsoe Downes’ education is bringing her closer to her intended destination — returning home to the Winnebago tribe in Nebraska with her…

ASU Law to honor Africa’s first elected female head of state with 2025 O’Connor Justice Prize

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first democratically elected female head of state in Africa, has been named the 10th recipient of the O’Connor Justice Prize.The award,…