The title of doctor, whether medical or academic, carries a certain weight. After all, you don’t become one without a great deal of time, dedication and expertise.

ASU Professor Patricia Friedrich and her husband, ASU Associate Professor Luiz Mesquita, are both doctors. Yet when they attended professional events together, she noticed an odd discrepancy.

“People would refer to him as ‘doctor’ and, in the same breath, refer to me as ‘Patty,’” she said. As a sociolinguistSociolinguistics is the descriptive study of the effect of any and all aspects of society, including cultural norms, expectations and context, on the way language is used and the effects of language use on society., it made her wonder.

Unbeknownst to her at the time, the same thing had other female doctors scratching their heads; in particular, doctors Anita Mayer and Julia Files from Mayo Clinic Arizona, who recruited Friedrich and her linguistic skills to look further into it. The research team, which also included two of Friedrich’s students, Trevor Duston and Ryan Melikian, published a study on the phenomenon recently, which found that female doctors introduced by men at formal gatherings were less likely to be referred to by their professional title than were male doctors introduced by men.

The researchers analyzed video footage of 321 speaker introductions at two separate formal medical gatherings. Various data were codified by pairs of researchers, one female and one male, to ensure as little bias as possible.

They found that regardless of the speaker’s gender, female introducers were 96 percent more likely to use professional titles compared with 66 percent of male introducers. This is consistent with researchers’ expectations based on past studies that have found that women tend to use a more formal register across the board compared with men, Friedrich said.

The findings were relatively similar for same-gendered introducers and speakers, with female introducers of female speakers using professional titles roughly 98 percent of the time, and male introducers of male speakers using professional titles roughly 72 percent of the time.

But when it came to opposite genders introducing each other, the biggest discrepancy was found: Female introducers of male speakers used professional titles roughly 95 percent of the time, while male introducers of female speakers used professional titles roughly 49 percent of the time.

That’s statistically significant, Friedrich said, and was something female researchers on the team had anticipated based on personal experience.

“We wanted to see if the differences that doctors who happen to be women were noticing in their own professional lives could be quantified,” said Friedrich, who is in the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences. “And that is what we were able to confirm.”

One of the things she and the rest of the research team agree on is that the discrepancy is not necessarily intentional. According to Friedrich, one male doctor reported that addressing female doctors by their first name instead of their professional title was an attempt to convey that they were equals.

Another reason behind the discrepancy could be that forms of address for men vs. women are so strongly socially embedded in us that we don’t realize we’re differentiating, Friedrich added.

Either way, the possible repercussions are real.

“Some people say, what’s the big deal? It’s such a minor thing, why should anybody care?” she said. “As a social linguist, my belief is that little things in language are often indicative of social practices that usually do have ramifications.”

Those ramifications can include roadblocks to professional development, being perceived as having less authority and being taken less seriously in one’s profession.

And it happens across multiple professions in which titles are common, such as academia, law and among members of the clergy, Friedrich said.

Since the results of the study were published, one of the formal medical gatherings from which the research team gathered data has changed its standard of introductions, advising attendees to include formal titles in introductions of all speakers.

“I think this is one of those linguistic situations where we called attention to something that might not be intentional but now we have the ability to try and change it by initiating practices that are more even across genders,” Friedrich said. “Sometimes language changes because society changes, and sometimes society changes because language changes.”

Friedrich and the team were pleased that the study proved to be so productive and are motivated by the results to build on it in the future, considering, as she said, that “it’s applicable to so many realms.”

More Health and medicine

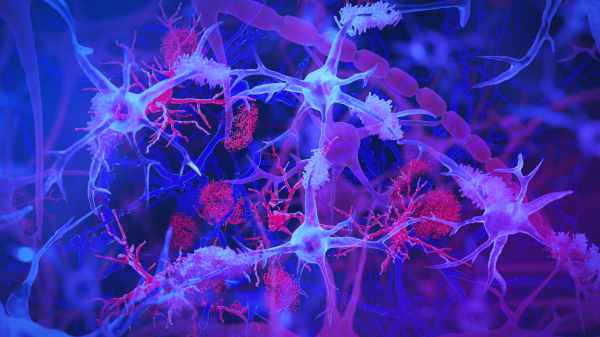

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

Arizona State University and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute researchers, along with their collaborators, have discovered a surprising link between a chronic gut infection caused by a common virus and…

ASU, University of Wisconsin partner to empower Black people to quit smoking

Arizona State University faculty at the College of Health Solutions are teaming up with the University of Wisconsin to determine which treatments work best to empower Black people to quit…

New book highlights physician wellness, burnout solutions

Health care professionals dedicate their lives to helping others, but the personal toll of their work often remains hidden.A new book, "Physician Wellness and Resilience: Narrative Prompts to Address…