Imagine working for the harshest corporation in the world.

Naturally, they want to maximize production and growth. This is done by investing in lots of low-wage employees, rather than fewer well-paid workers. When production needs to be ramped up, more workers are brought on like holiday employees at a warehouse.

When they’re of a certain age, they’re sent out to die working, with no further help from corporate. All of this produces a large, thriving company.

Ant colonies will never make the list of best places to work, but those are some of the ways they grow successfully. A new study by Arizona State University scientists revealed what makes a thriving colony.

Video by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

“People will be interested to know there’s a lot more going on below the surface here in terms of organization and similarity to us than you might expect just by looking at ants scurrying around on the surface,” said lead author Christina Kwapich.

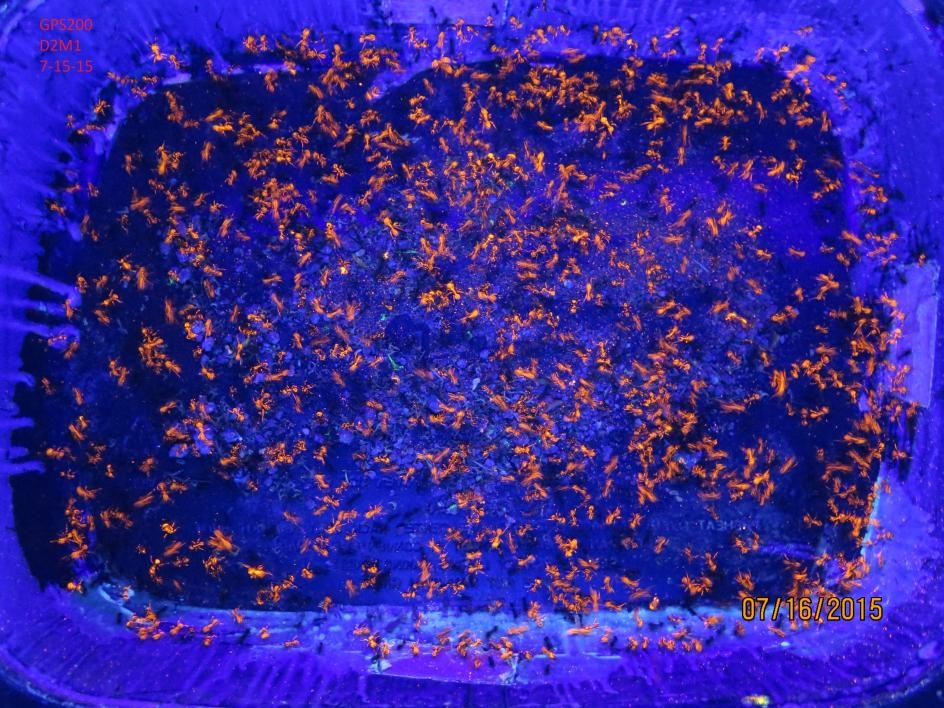

The study took a year and a half, and it involved counting almost 300,000 individual ants. The researchers were interested in how colonies performed in terms of worker loss and production, and how that affected colony reproduction.

“We went out and measured how many foragers, or ants that came out to collect food, died in a single year and then how many of those workers a colony was able to replace,” said Kwapich, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Life Sciences at ASU. “We did that because big colonies produce more new queens and males than small colonies, and we wanted to see why some colonies are better or worse.”

Colonies that produced the most workers, had the largest territories and did well seasonally were the colonies that produced smaller workers.

Ants bring out their dead. Two and a half acres of colonies produce enough dead ants to weigh as much as a house cat or a newborn baby.

The colony, which is the entire community of queens, workers, larvae and so on, is like a factory. There’s a division of labor, like Henry Ford’s production line. As ants age, they change jobs. The colony needs to allocate labor in an adaptive way.

Christina Kwapich says ant colonies around South Mountain Park/Preserve can be 20-30 feet deep or more, with the queen residing at the bottom and food stores in the midsection.

Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

“In one of our other studies, we showed that the proportions of colonies of ants who do certain jobs change throughout the year in a way that facilitates the production of new queens and winged males and workers at different times,” Kwapich said. “They’re maximizing production by changing the labor ratios in the colony.”

There’s no cozy retirement awaiting. Foragers don’t live long. It’s like building a bridge for the Japanese army in Thailand. Forager ants turn over 1.7 times per month.

“When the ant comes to the surface and begins collecting food, that’s at the very end of her life,” Kwapich said. “She’ll do that for about 18 days before she dies. The ants had the amount of investment that is corresponding to the life they’ll have on the surface. The colony doesn’t keep investing in them once they start doing this job. They don’t waste the fat young ones; they stay deep in the nest.”

It’s a little economics problem, Kwapich said. More seeds, more larvae, more workers mean a bigger, healthier colony. “That’s the goal of every colony: to reproduce,” she said.

Myrmecologists — entomologists who specialize in ants — know that if a colony has multiple queens, there’s going to be more worker production. That wasn’t the case with desert seed-harvesting ants, the subject of the study.

“What we actually found was that all the colonies had just a single queen, and what differed was the number of fathers that occurred in each colony,” Kwapich said. “We found that colonies with fewer fathers did better than colonies with multiple fathers. What this means is that during the mating flight, a queen either mated with more or less males before starting her colony and letting it grow into this creature with a division of labor and all sorts of interactive parts.”

The paper will be released in the August issue of Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. Kwapich’s co-authors were Bert Hölldobler and former ASU faculty member Juergen Gadau.

Incidentally, Kwapich was inspired to go into myrmecology by reading Hölldobler’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Ants” when she was a kid.

Top photo: ASU entomology postdoctoral researcher Christina Kwapich takes a sample of ants from a colony in a wash in the South Mountain Park/Preserve in Phoenix on July 18. Her recent research has focused on counting the annual turnover of worker ants within colonies. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Science and technology

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable social relationships. There are tons of such clubs on ASU's campuses…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as designing the future. The consortium marked 25 years in Washington, D…

Hacking satellites to fix our oceans and shoot for the stars

By Preesha KumarFrom memory foam mattresses to the camera and GPS navigation on our phones, technology that was developed for space applications enhances our everyday lives on Earth. In fact, Chris…