ASU researcher finds ways to reduce stress in shelter dogs

Doctoral candidate in Canine Science Collaboratory in the Department of Psychology examines sleepover program

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. To read more top stories from 2017, click here.

“Who’s a good dog? You are, aren’t you? Yes, you’re the best dog that ever was.”

But is he really a good dog? Can you really tell when you’re doing a meet-and-greet in the shelter? Is that how he’s going to be when you take him home? Are you getting Lassie or the Hound of the Baskervilles?

These were the sorts of questions that led to a study done by an Arizona State University researcher.

Lisa Gunter, a doctoral candidate studying behavioral neuroscience at the Canine Science Collaboratory in the Department of Psychology, began the project as a pilot study at Best Friends Animal Sanctuary in Kanab, Utah, the largest no-kill shelter in the country. About 1,600 dogs and cats live there, visited by about 30,000 people per year. It’s a popular vacation destination for pet lovers. People come and take weeklong “volunteer vacations.”

Gunter looked at the sleepover program offered by Best Friends, where visitors can take a dog back to their hotel room for the night.

The question she had was this: Is their behavior on the sleepover predictive?

“We wanted to see how one night out of the shelter would impact the dogs,” Gunter said. “Is that what someone will see in their house? … That has been a challenge in sheltering.”

Gunter measured levels of cortisol, a diurnal hormone that is a measure of stress. She also took a behavioral snapshot of each dog, asking such questions as: What’s he like on a leash? What’s he like when he sees another dog? What’s he like when you come into his kennel?

“We saw one night out significantly reduced their cortisol,” Gunter said. “When they returned the next day, it was the same. We knew it at least dropped for one night.”

Lowered stress levels could allow the dog to behave more naturally, giving people a better view of the dog's true personality.

The researchers took cortisol samples at three time points: the dog at the shelter, the dog at the sleepover and the dog back at the shelter.

“We’re trying to get more at the dog’s welfare, how they’re feeling on a larger timescale, not just 10 or 15 minutes,” Gunter said. “When we saw the cortisol had significantly reduced on just one overnight, that was pretty exciting. We didn’t imagine that just one night out would make a difference.”

Anecdotally, people who took a dog home for a sleepover reported that after the dog settled down, it would immediately go for a long sleep.

“Is sleep potentially a component to their welfare?” she said. “Getting good, uninterrupted sleep could benefit them as well. That could be one mechanism by which we’re seeing this reduction in cortisol. The dogs are getting a good night’s sleep. That’s something they can’t get at the shelter because they have a lot of noisy neighbors.”

Gunter has been carrying out the study in collaboration with a researcher at Carroll College in Helena, Montana. They were recently awarded a grant to carry out this study at four shelters across the U.S. Instead of a one-day baseline, they’ll be collecting a two-day sample.

Shelters are constantly looking for ways to get animals into homes.

“For a long time in sheltering it was thought dogs would be more adoptable if you just taught them to sit, if you just taught them to be well-behaved,” Gunter said. “That’s not necessarily the case. That’s not what our lab has found. There are behaviors related to companionship of people in a meet-and-greet setting when the person is getting to know the dog.”

They’ve found two behaviors that people respond to: when the dog lies down next to the person and whether the dog responded to an invitation to play.

“We’re a behavior and cognition lab, so we really try to understand what the animal is experiencing by looking at its behavior,” Gunter said. “Until the time we can have a conversation with them, for now we’re left with observing their behavior. We’re essentially detectives, trying to gather the information to have our best understanding of what the dog is experiencing. It’s the best we can do, without being dogs.”

Top photo: Lisa Gunter plays with her 11-year-old rescued border collie Sonya outside the Psychology building on ASU's Tempe campus. Gunter, a doctoral candidate studying behavioral neuroscience at the Canine Science Collaboratory in the Department of Psychology, found that shelter dogs benefit from sleepover programs like the one offered at at Best Friends Animal Sanctuary in Kanab, Utah, the nation's largest no-kill animal shelter. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Science and technology

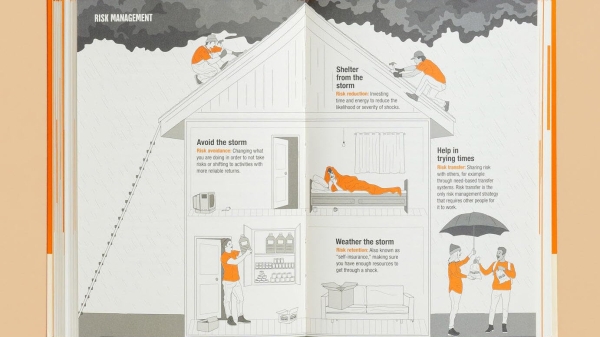

ASU author puts the fun in preparing for the apocalypse

The idea of an apocalypse was once only the stuff of science fiction — like in “Dawn of the Dead” or “I Am Legend.” However these days, amid escalating global conflicts and the prospect of a nuclear…

Meet student researchers solving real-world challenges

Developing sustainable solar energy solutions, deploying fungi to support soils affected by wildfire, making space education more accessible and using machine learning for semiconductor material…

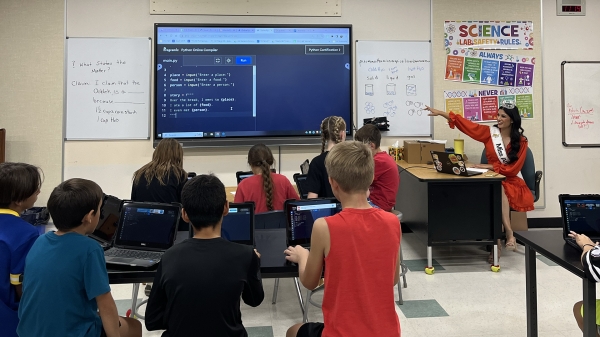

Miss Arizona, computer science major wants to inspire children to combine code and creativity

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable spring 2024 graduates. “It’s bittersweet.” That’s how Tiffany Ticlo describes reaching this milestone. In May, she will graduate…