Print book sales have been on the decline since the Great Recession with one exception: graphic novels.

Trade group ICv2 says the novel-in-comic-strip format has gone over $1 billion in annual sales, with top sellers moving up to 150,000 units a week. Taking advantage of the momentum, ASU is bringing a leading industry voice to deliver a lecture and communication workshop on the rising popularity of the visual art form.

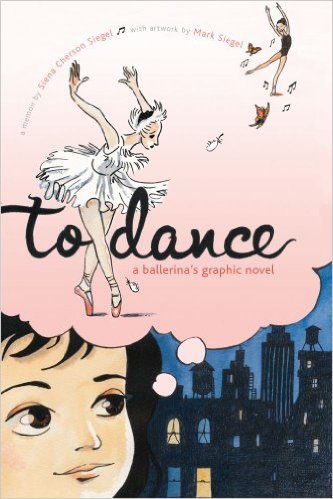

Award-winning author and illustrator Mark Siegel is the founder, editorial and creative director of First Second Books, the Macmillan publisher of graphic novels in every age category.

Siegel’s lecture, “The Great American Graphic Novel” on Thursday afternoon in Payne Hall on the Tempe campus, will cover the history of comics and graphic novels, the creative process, and the importance of the medium as a tool for literacy in an increasingly visual culture. The lecture is free and guests are asked to RSVP online.

And on Friday, ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination and the Institute for Humanities Research are hosting a workshop with Siegel that pairs local comic artists with ASU faculty to create an original, visual narrative of their research.

ASU Now reached out to Siegel in advance of his Tempe visit.

Question: What do you account for the rise of the graphic novel in the past decade?

Answer: Comics have deep roots in America whether it’s the newspaper strip or the superhero comics. They have a deep place in the American psyche, and it’s an American form of storytelling, even though it’s all over the world.

A decade ago the sounds coming out of the comic book industry were really grim and looked hopeless. Then a couple of things happened: Hollywood began basing movies on graphic novels coupled with the emergence of manga, which has been popular in Japan since the 1960s.

Suddenly, there were millions of dollars changing hands, huge sections of graphic novels appearing at bookstores. Publishers began asking, “What is this? And why are we missing out on these millions of dollars?”

It’s the fastest growing category in publishing, and America is the leading in this new graphic novel form.

Q: What is the difference between a comic book and a graphic novel?

A: If you ask different people, you’ll get slightly different answers. Some people are super militant about the differences.

For me, comics are a medium. So when you say comic, it’s generally the comic form, paneled and has word balloons.

A graphic novel has become a publishing category. It doesn’t have to necessarily be a novel, but it includes fiction, non-fiction and memoirs. It uses the comic form, but it has a spine like a book, not a pamphlet. Typically, when you say comic, that’s usually a pamphlet. That’s how I gauge it in a very practical way.

Mark Siegel wrote "To Dance: A Ballerina's Graphic Novel" with his wife, Siena Cherson Siegel, in 2006.

Q: What is the power of the graphic novel?

A: We’re moving into an age where there’s a visual literacy that can go as deep and as substantive as prose literacy. People are being raised to think both visually and verbally. The graphic novel does those two things, and the dance of those two produces an experience.

There’s an interesting thing that cartoonist Art Spiegelman said about word balloons. That is, if they’re done well, they’re not like chunks of paragraphs or texts of words, but rather they’re puffs of thought. Brain scientists say that’s how your brain actually works.

We don’t really think in paragraphs or full sentences, but more like phrases that kind of clump together. The really good comics authors do that really well. There’s a pacing of thought that they establish. It can reach deeply, and it’s an active mental act.

Q: Let’s talk numbers. How big is this industry?

A: It’s huge numbers. Between comics, manga and graphic novels, it’s a big industry.

A title like “The Olympians,” a retelling of the Greek myths, we’ve sold well over 350,000 copies. So while that sounds like a lot of copies, there’s a lot of time that’s involved and you have to be a little nuts to do one of these things.

What’s interesting about the other book models is that it’s like the Hollywood blockbuster: it’s either huge or it dies on the spot. Graphic novels aren’t like that. If they stick, they can keep selling and selling and selling. They have this really long tail. But it’s not a quick money scheme; it’s more of a long-term investment.

Q: What do you hope to convey in your upcoming Feb. 16 lecture and Feb. 17 workshop?

A: The lecture will be a fun and lighthearted history of comics in America to see where we are today.

The presentation the following day is a behind-the-scenes of making a comics project. We’ll team scientists with local comic book artists and develop a rough mockup of a non-fiction comic.

It’s an event that may be even bigger than we had anticipated. Something wants to happen here.

Top photo: A panel from Sin City, a neo-noir comic by writer Frank Miller. The 2005 movie adaptation and a subsequent sequel helped propel the popularity of the graphic novel. Courtesy of YouTube.com.

More Science and technology

From wanna-be high school math teacher to Regents Professor

It’s a bit difficult to describe the work Stephanie Forrest does as director of Arizona State University’s Biodesign Center for Biocomputation, Security and Society.Her ASU biography lays it out this…

Regents Professor recognized as pioneer in educational technology

Reading can transport people around the world — and back and forth in time.That’s what Danielle McNamara has helped tens of thousands of students do.McNamara is the executive director and…

Professor’s expertise in technology transfer leads to top faculty honor

Universities spend billions of dollars on research, and the process of transforming that work into goods and services for the public is more important than ever.ASU Professor Donald Siegel is an…