There was a time when the whole country watched the evening news.

They showed dead people on TV then, slippery pallored American corpses dragged through wet jungle by their arms.

The news did not close with a “bright spot” about an amputee kid ballroom dancing or a squirrel on water skis. In those days it was news, not a half-hour of chuckles and fun.

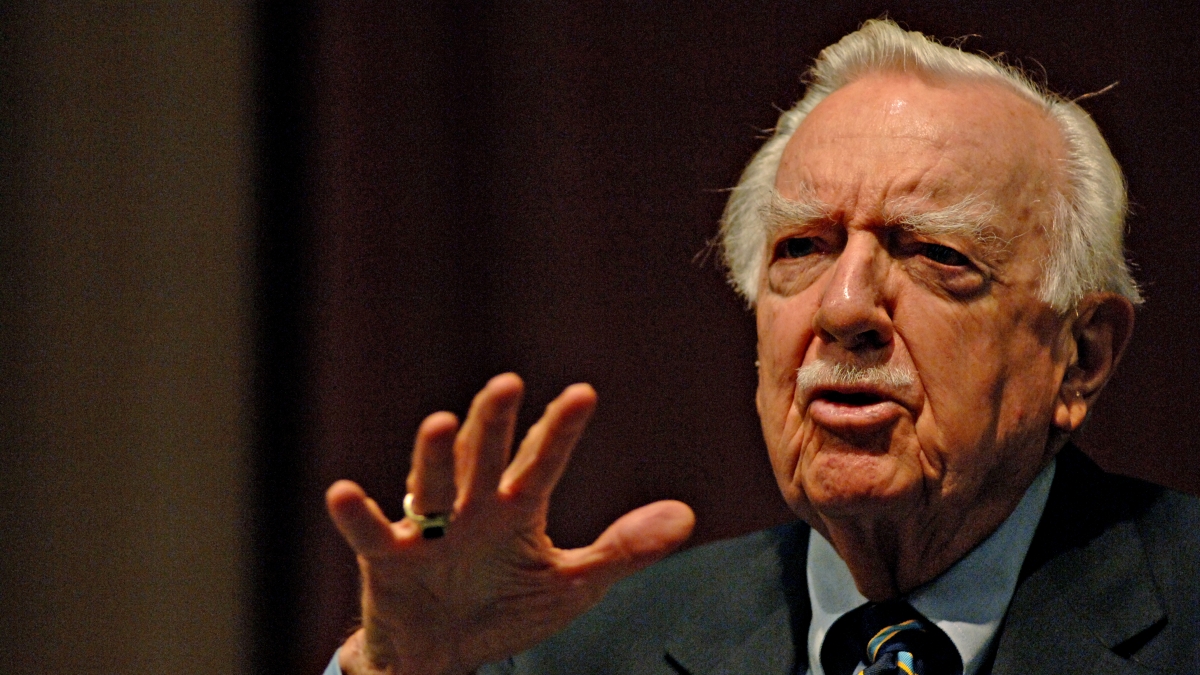

“And that’s the way it is,” intoned the man who gave us the CBS Evening News every night. And the world was that way. No more, no less. You knew that because you knew what that man said was true. That was the way it was.

That was Walter Leland Cronkite Jr., and Nov. 4 would have been his 100th birthday.

The namesake of Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication had a lot of nicknames. “Uncle Walt.” “The Most Trusted Man in America.” “Old Ironpants.”

When Cronkite retired in 1981, the Washington Post declared he was better known than John Wayne or Clark Gable. From 1962 to 1981, he was the voice of 20th-century America, bringing home the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the race to put men on the moon, the Vietnam War and the Iran hostage crisis.

He reported after the Tet Offensive in 1968 that America was not winning in Vietnam. “For it seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate,” he wrote in an editorial.

When President Lyndon Johnson heard it, he famously remarked, “If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America." Weeks later Johnson announced he wasn’t running for re-election.

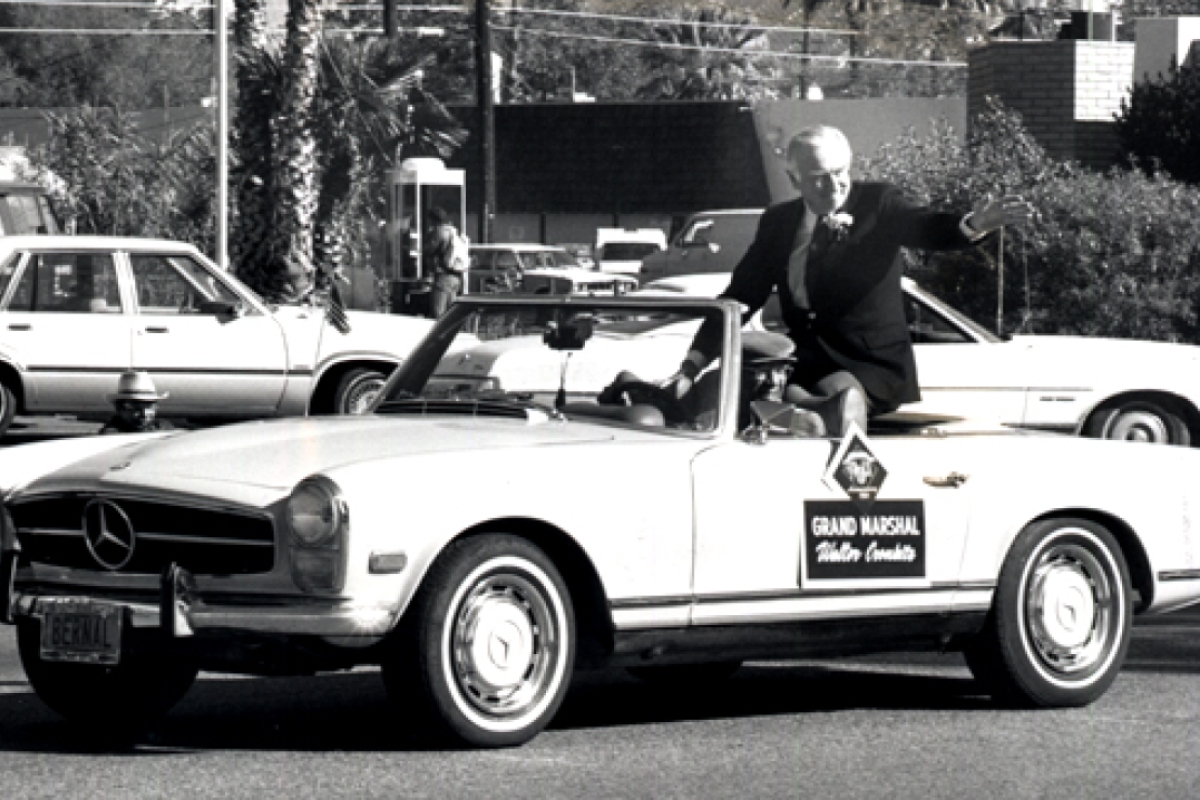

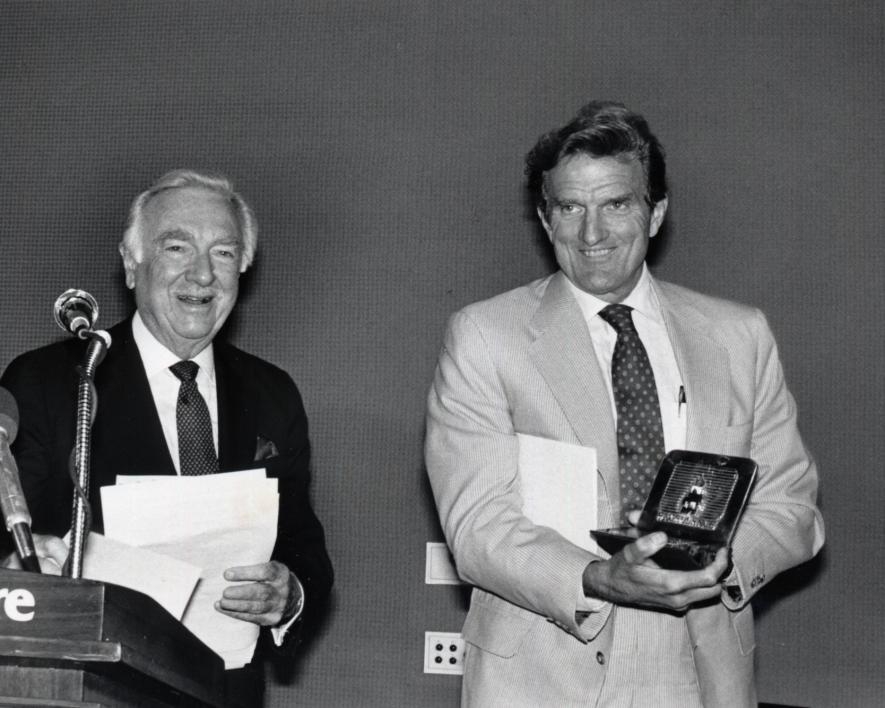

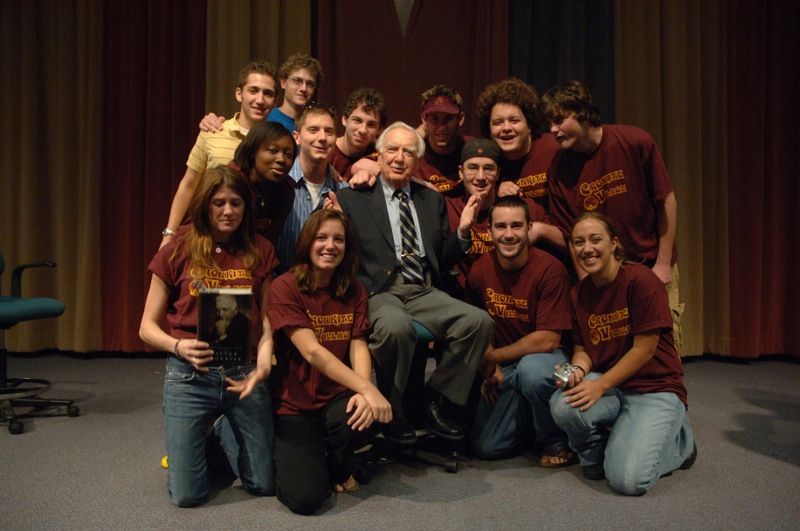

Doug Anderson directed the Cronkite School from 1987 to 1999. When Cronkite visited ASU, he was in his early 70s, and he ran Anderson ragged putting in 16-hour days brimming with breakfasts, classroom lectures, small group meetings and evening events with friends, alums and donors. Cronkite’s visits to the State Press newsroom were unforgettable to awestruck student journalists. (See below for a firsthand account of one visit.)

“He would connect like that,” Anderson said. “He truly was Uncle Walter when he came for these visits.”

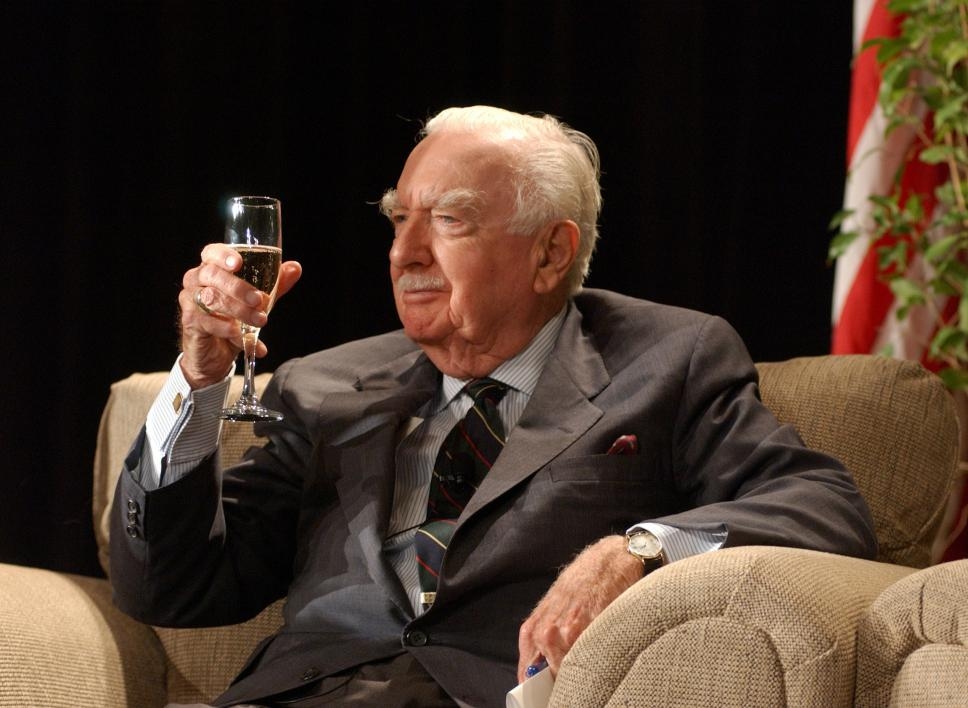

Cronkite — who died July 17, 2009, at the age of 92 — always referred to the school as “our school,” Anderson remembered.

“He never referred to it as the Cronkite School,” he said. “If he were talking to a student, he referred to it as ‘our school.’ It was always ‘our school,’ and I truly and sincerely believe he had enormous pride in his affiliation with the school that was named for him. It grew, I think, that affinity and that affection through the years.”

Cronkite remained the quintessential reporter, recalled Chris Callahan, dean of the Cronkite School.

“Any time you spent with him, he would tell great stories, but mostly he wanted to hear from our students about where they were from, their goals and dreams and aspirations, and I think that spoke so much of who Walter was as a person,” Callahan said. “He was just a joy and a delight to be with.”

Like everyone else, Callahan could not help being starstruck in his presence.

“I grew up watching the CBS Evening News with him, so the first few times I spent time with him I was nervous,” he said. “And he knew that. He had a wonderful way with people.”

Both Callahan and Anderson remarked on Cronkite’s sense of humor. He was a faithful son and always called his mother when he was on the road, Anderson remembered.

He told Anderson a story about visiting his mother in an assisted living home in Washington, D.C. She was sitting at a table with other ladies.

“I’m sure anyone in that room at that time would have known who Walter Cronkite was,” Anderson said.

His mother jumped up and greeted him. She introduced all the ladies to him, then looked at Walter, and said, “Their sons put them in here too.”

“He was a very funny guy,” Callahan said, citing a few stories unfit for print. “He loved life. It goes back to that reporter’s zest for learning something new every day. The way he interacted with people was so natural.”

It’s unlikely another newsman of his stature will come along, given the current state of media.

“I would agree with that wholeheartedly,” Anderson said. “Even when he signed off in his final broadcast, I think that broadcast drew 18 or 20 million viewers. That kind of audience and that kind of trust placed on a journalist, I can’t imagine that being equaled.”

Part of that was being the right person at the right time in American history, Callahan said.

“With the proliferation of all these different news sources, you’re never going to have another Walter,” he said. “There’s a lot more choices now than three national newscasts. ... He was that person who every night you could go home and relay on getting a concise, accurate synopsis of the events of the world.”

Editor's Note: Below, ASU Now reporter Scott Seckel tells the story of when he first met Walter Cronkite.

I grew up in a CBS household. We watched the evening news every night, and my grandfather did not tolerate chitchat while Walter Cronkite spoke. We didn’t know what the voice of God sounded like, but we were all pretty sure He sounded like Cronkite.

Flash-forward about 20 years, when I was a student reporter on ASU’s State Press. We were told Cronkite was going to visit our dank basement newsroom.

In walked an impeccably dressed legend. “Starstruck” doesn’t even begin to cover it. I’ve met a fair number of celebrities since then and never felt that way about any actress or athlete. He sat on a desk and chatted with us about our paper and what we did. All the time I could not believe that Walter Cronkite himself sat about 10 feet from me.

He proceeded to tell a story about one of his first professional assignments. (He himself had dropped out of college.) The details were fuzzy after all these years, but with the reconstructive help of a colleague who was there and the Washington Post archives, this is what he told:

He worked at the Houston Press, earning $15 a week. One of his tasks was picture chasing, a chore that thankfully doesn’t exist anymore. When someone died or made the news, young reporters were sent to their home to beg for a picture of the deceased.

Cronkite went to the house and knocked on the door. No one answered. He waited. Still no answer. He went around to the back of the house and saw a picture of the man. (It either sat on a mantel or a piano. Cronkite said “piano” that afternoon. The Post story says a mantel.)

He tried the back door. It was unlocked. He had been ordered to get a picture, and he wasn’t coming back to the newsroom empty-handed. He opened the door, dashed inside, stole the picture and raced back to the paper.

It turned out to be the wrong house. He had stolen a picture of the dead man’s neighbor.

Special thanks to Marty Sauerzopf '89, current city editor at City News Service, Los Angeles; former State Press editor-in-chief.

More Law, journalism and politics

Exhibit uses rare memorabilia to illustrate evolution of US presidential campaigns

After one of the most contentious elections in history, a new museum exhibit offers a historical perspective on the centuries-old American process.“We The People! Electing the American President” had…

TechTainment conference explores the crossroads of law, technology, entertainment

What protections do writers, actors, producers and others have from AI? Will changing laws around name, image and likeness (NIL) eliminate less lucrative college sports programs?And what does…

How to watch an election

Every election night, adrenaline pumps through newsrooms across the country as journalists take the pulse of democracy. We gathered three veteran reporters — each of them faculty at the Walter…