Finding a balance: Sustainable energy vs. the natural landscape

These wind turbines and solar arrays are positioned to catch the wind funneled through San Gorgonio Pass just west of Palm Springs, California. Because the turbines do not require much land, solar arrays are an ideal accompaniment.

Renewable energy alternatives to fossil fuels are being tested around the world, but their acceptance has hardly been seamless. Many communities have resisted, saying installations such as wind farms intrude on natural landscapes.

In one case, a group of developers has been trying to build a series of offshore turbines near Cape Cod, but they've been stymied by local conservationsts who don't want the Atlantic horizon interrupted.

Despite such conflict, scientists say it remains important to develop a sustainable energy future. A cross-disciplinary team of researchers has come together to make this their goal.

The team consists of five veterans from different fields ranging from sustainability, to environmental planning to landscape architecture.

Mike Pasqualetti, a professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, and his colleagues have co-authored and edited a book newly published by Routledge press, The Renewable Energy Landscape: Preserving Scenic Values in our Sustainable Future.

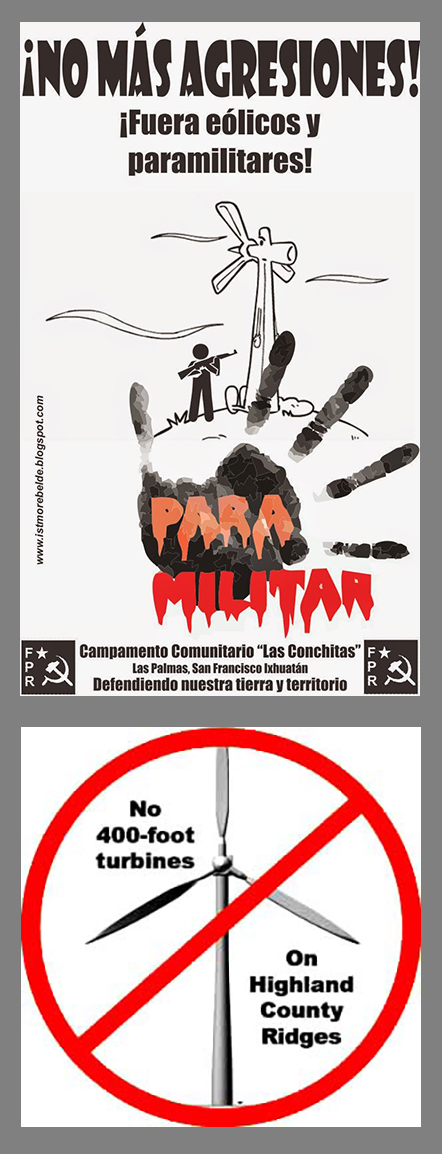

Renewable energy developments globally have been met with concern. These protest messages are from Oaxaca, Mexico and western Virginia.

The book aims to address the tension between conservation efforts and the need to develop sustainable energy alternatives such as wind and solar. The main cause of this conflict, according to Pasqualetti, is the considerable change that the infrastructure brings to natural landscapes.

“For the most part, it is an aesthetic intrusion,” said Pasqualetti. “There are two main groups of opposition. The people living nearby, and the people who don’t want the vistas they’ve always enjoyed to be altered.”

These groups of people have proven their ability to slow development or halt it completely, through lobbying, environmental whistleblowing or other tactics. Their opposition has made developers pay attention to the possibility and cost of lawsuits. Those costs may deter them when deciding whether or not to invest in alternative energy.

The book however, is not intended to discredit the landscape quality concerns, but rather to offer a responsible compromise. If a sustainable energy future is a must, then perhaps the infrastructure could be built in manner where its disruptive effect on the landscape is minimized.

This is the line that Pasqualetti and his fellow researchers are trying to draw. While there is a basic level of intrusion that comes with a 300-foot wind turbine or a five acre solar field, there are ways to minimize the number of people who feel affected.

Strategic placement of new energy infrastructure is very possible, Pasqualetti said. Solar farms, for example, can be placed in many locations, as they have been in Arizona already. Wind farms can be hidden too, by placing them just far enough offshore so that their turbines cannot be heard and are barely visible. While there will undoubtedly still be some environmental issues concerning wildlife, a number of potential problems can be avoided through careful planning and placement.

“To be frank, I think the opposition is still minor, we just don’t want it to be major. Don’t let ‘perfect’ be the enemy of the ‘good,’” Pasqualetti said.

The book’s researchers aren't alone in their vision of responsible alternative energy development. Experts from the private sector share their enthusiasm for a strategic transition into the next generation of energy infrastructure.

Paul Gipe, a wind energy industry analyst with over 40 years of experience and a published author on the topic, joined in the conversation.

“The word transition is a very important term in this. We must make the change to renewable energy. It will happen one way or the other, but it's better if we do it on our own terms rather than in panic,” Gipe said. “If we don't do it in panic, we can do it right.”

In order to meet the energy demands of an increasingly industrialized world, renewable energy systems are going to require a lot of hardware. This hardware will inevitably become a part our landscapes.

Gipe encourages planners and developers to “do the projects in harmony with the landscape and with the people who live on the landscape.”

Researched and drafted by Gavin Maxwell, Walter Cronkite School of Journalism & Mass Communication, and School of Geographical Sciences & Urban Planning

More Environment and sustainability

ASU to host new Global Coordination Hub

In a new partnership between the global research network Future Earth and Arizona State University, the Julie Ann…

A world full of plastic ... not fantastic

Editor’s note: This is the seventh story in a series exploring how ASU is changing the way the world solves problems.…

Team wins $10M XPRIZE Rainforest competition for novel solution

Several Arizona State University experts are on a team that created a new way to put a price on the rainforest in order to save…