The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today issued a final rule establishing that over-the-counter consumer antiseptic wash products containing certain active ingredients can no longer be marketed.

Companies will no longer be able to market antibacterial washes with these ingredients because manufacturers did not demonstrate that the ingredients are both safe for long-term daily use and more effective than plain soap and water in preventing illness and the spread of certain infections. Some manufacturers have already started removing these ingredients from their products.

This final rule applies to consumer antiseptic wash products containing one or more of 19 specific active ingredients, including the most commonly used ingredients: triclosan (TCS) and triclocarban (TCC). These products are intended for use with water, and are rinsed off after use. This rule does not affect consumer hand “sanitizers” or wipes, or antibacterial products used in health-care settings.

Video: What consumers need to understand about antimicrobials.

“Consumers may think antibacterial washes are more effective at preventing the spread of germs, but we have no scientific evidence that they are any better than plain soap and water,” said Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in an FDA statement. “In fact, some data suggests that antibacterial ingredients may do more harm than good over the long-term.”

For ASU scientist Rolf Halden, the ruling has been an environmental and public health victory that was a long time in the making.

"It is a public-health victory that will limit unnecessary and potentially harmful exposures in consumers who long have been misled about both risks and benefits of these antimicrobials,” says Halden, director of the Biodesign Center for Environmental Security at ASU's Biodesign Institute.

Rolf Halden

“Most people don’t use personal-care products correctly and are unaware of the legacy that they are leaving behind, which lasts decades or longer. The widespread use of antimicrobial compounds offers no measurable benefit for the average consumer yet creates a legacy pollution that can be traced back for half a century in the sediments of our drinking-water resources.”

Halden, a professor in ASU’s SchoolThe School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment is part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, studies the broad interconnectedness of the water cycle and human health, with special emphasis on the role of man-made products and human lifestyle choices on environmental quality. It has increasingly led him on a journey from scientific discovery to reforming public policy on the antibacterial soap issue.

Halden’s team was the first to find significant concentrations of TCC and TCS dating back to the 1950s in sediments of New York’s Jamaica Bay and Baltimore’s Chesapeake Bay, where they were discharged in treated domestic wastewater. More recently, Halden found the same antimicrobial ingredients contaminating Minnesota’s freshwater lakes, released into nearby waters from various human activities.

Halden’s team found the antimicrobials in wastewater treatment plants of over 160 U.S. cities, showing that half to three quarters of the chemicals did not degrade and persisted in sewage sludge. The problem with these substances is that their chemical structure is mostly foreign to nature. This leaves natural breakdown mechanisms and enzymes ineffective in destroying them.

“In the built environment, it is us, the creators and inhabitants, who store the non-green, recalcitrant chemistry in our bodies, mostly in adipose tissue, and in women also in breast milk,” Halden said.

Antimicrobials have been detected in human blood and urine. The compound TCS was even found in 97 percent breast milk samples, placing an unnecessary risk on newborns’ health.

TCS and TCC are known endocrine disruptors. These mimic hormones found in people and wildlife, with potential adverse impacts on sexual and neurological development. In collaboration with Laura Geer from the State University of New York, Halden and his team found various antimicrobials in newborns in Brooklyn and observed decreased gestational age at delivery in mothers exposed to TCC.

Geer said the study also yielded a link between women with higher levels of butylparaben, an antimicrobial commonly used in cosmetics, and shorter newborn lengths. The long-term consequences of this are not clear, but Geer adds that if this finding is confirmed in larger studies, it could mean that widespread exposure to these compounds will cause a subtle but large-scale shift in birth sizes.

The Minnesota legislature was so alarmed by these and other researchers’ findings that it instituted the first ban of problematic antimicrobials from all state agencies. Some companies, such as Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble, have announced that they are phasing out the compounds from some products.

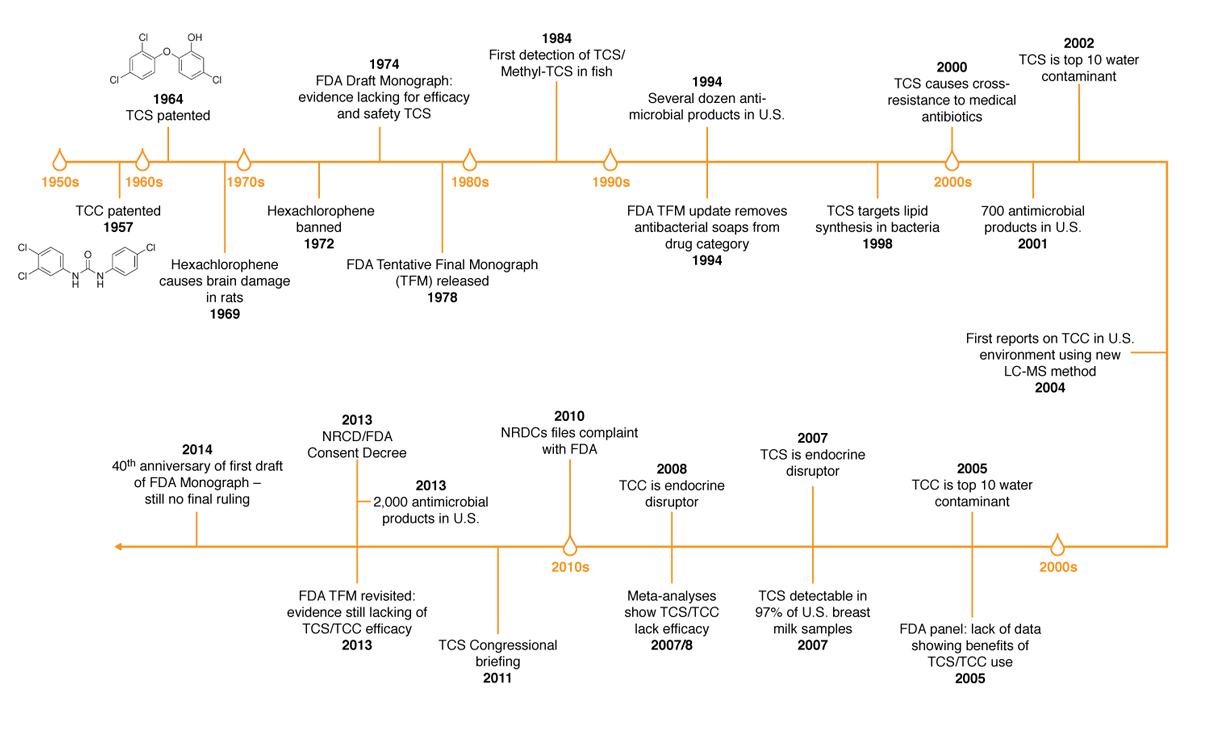

Prior to the landmark FDA ruling, there has been a long history of usage and regulatory actions concerning antimicrobials in personal-care products.

Halden knows that monitoring alone will not quell the rising tide of emerging contaminants. Regulation holds the key to truly effecting change. In February 2011, Halden participated in a congressional briefing panel in Washington, D.C., about the public health dangers of TCC and TCS.

The FDA issued a proposed rule in 2013 after some data suggested that long-term exposure to certain active ingredients used in antibacterial products — for example, triclosan (liquid soaps) and triclocarban (bar soaps) — could pose health risks, such as bacterial resistance or hormonal effects. Under the proposed rule, manufacturers were required to provide the agency with additional data on the safety and effectiveness of certain ingredients used in over-the-counter consumer antibacterial washes if they wanted to continue marketing antibacterial products containing those ingredients. This included data from clinical studies demonstrating that these products were superior to non-antibacterial washes in preventing human illness or reducing infection.

Antibacterial hand and body wash manufacturers did not provide the necessary data to establish safety and effectiveness for the 19 active ingredients addressed in this final rulemaking. For these ingredients, either no additional data were submitted or the data and information that were submitted were not sufficient for the agency to find that these ingredients are Generally Recognized as Safe and Effective (GRAS/GRAE). In response to comments submitted by industry, the FDA has deferred rulemaking for one year on three additional ingredients used in consumer wash products – benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride and chloroxylenol (PCMX) – to allow for the development and submission of new safety and effectiveness data for these ingredients. Consumer antibacterial washes containing these specific ingredients may be marketed during this time while data are being collected.

Washing with plain soap and running water remains one of the most important steps consumers can take to avoid getting sick and to prevent spreading germs to others. If soap and water are not available and a consumer uses hand sanitizer instead, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that it be an alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains at least 60 percent alcohol.

Since the FDA’s proposed rulemaking in 2013, manufacturers already started phasing out the use of certain active ingredients in antibacterial washes, including triclosan and triclocarban. Manufacturers will have one year to comply with the rulemaking by removing products from the market or reformulating (removing antibacterial active ingredients) these products.

The Center for Environmental Security is one of 15 centers in ASU’s Biodesign Institute and is jointly supported by ASU’s Global Security Initiative.

More Health and medicine

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

Arizona State University and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute researchers, along with their collaborators, have discovered a surprising link between a chronic gut infection caused by a common virus and…

ASU, University of Wisconsin partner to empower Black people to quit smoking

Arizona State University faculty at the College of Health Solutions are teaming up with the University of Wisconsin to determine which treatments work best to empower Black people to quit…

New book highlights physician wellness, burnout solutions

Health care professionals dedicate their lives to helping others, but the personal toll of their work often remains hidden.A new book, "Physician Wellness and Resilience: Narrative Prompts to Address…