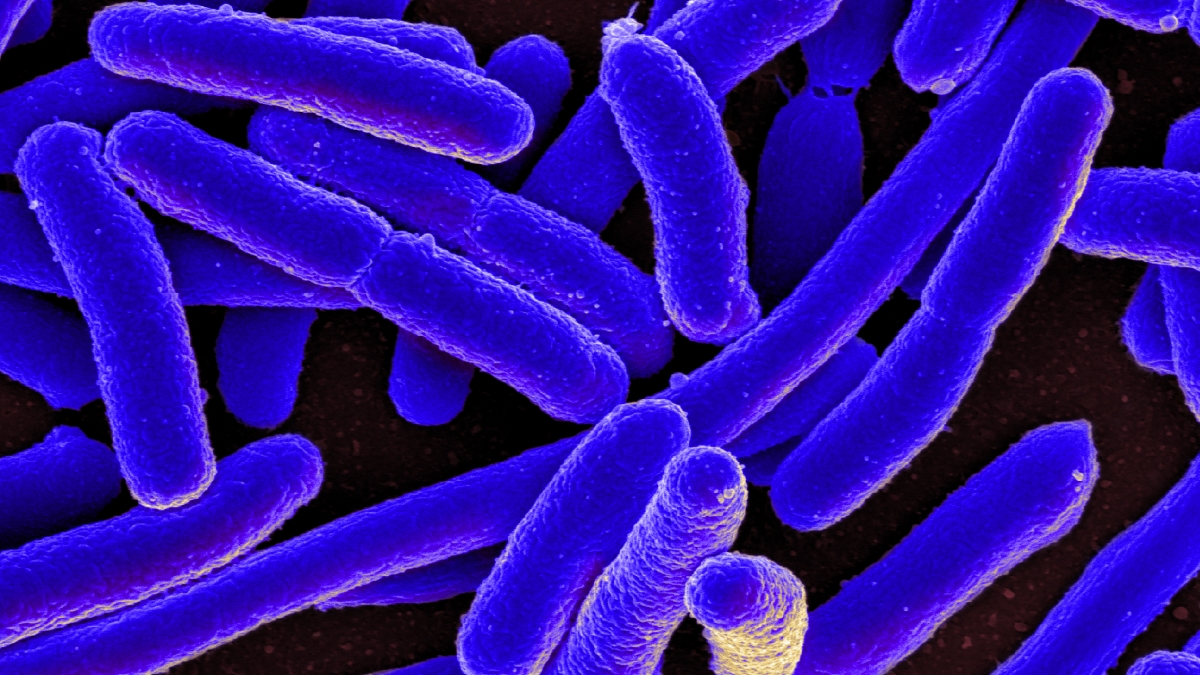

Last week the Department of Defense issued a report detailing the case of a 49-year-old Pennsylvania woman who had a rare E. coli infection resistant to all antibiotics, including colistin, which is a harsh drug used only on the sickest patients.

The superbug is the first known case of its kind in the United States, and the report sparked strong reactions. The concern was that traits of the infection could jump to other bacteria that respond only to colistin, creating an unstoppable superbug.

ASU Now talked with Dr. Shelley E. Haydel, an associate professor in the School of Life SciencesThe School of Life Sciences is an academic unit in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. and a researcher in the Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, about how realistic the threat is.

Question: The World Health Organization said the superbug is the biggest threat to global health.

Answer: I wouldn’t say that. A couple of the headlines were quite misleading. I don’t remember all of them, but they were all —

Q: We’re going to die.

A: “We’re going to die and it’s not treatable.” That’s not true. If I could explain as simply as possible what was in the paper that came out that caused all these headlines, and why it’s not the end of the world as we know it related to microbiotic resistance, and why some of the information from that report is important, and why it’s not the end of the world.

Everyone has a chromosome, including you and me. Bacteria have these little small plasmid DNA molecules, separate from the chromosome. These can be passed into another bacterium. The chromosome can’t, but these can be passed easily. This is one of the ways antibiotic resistance is spreading rapidly.

What this paper showed is that one of the last-resort antibiotics, which is called colistin, for the first time they found the resistance gene for colistin on a plasmid. Previously the resistance gene had always been in the chromosome. So, mutations that occur in the chromosome, I can’t pass that. I can’t pass that to anyone, but these plasmids I can.

ASU researcher Shelley E. Haydel. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

One of the reports actually described colistin resistance in CRE. CRE is one of the big issues in antibiotic-resistance bacteria because of this first C, which stands for carbapenem. Carbapenem is part of a group of antibiotics that are reserved for people in ICU, who are really, really sick.

Q: Heavy-duty stuff.

A: Heavy-duty stuff, and we really didn’t see that before the last five to 10 years. It was our best antibiotics that work against a lot of different bacteria, so save those for the sickest people. Now we have resistance to carbapenems. So what we’re seeing in the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae — which is what the E stands for — this is the only antibiotic that would work for patients with CRE.

Now, this antibiotic was taken off the market 50 or 60 years ago because it destroyed your kidneys. Now we’ve gone back to that antibiotic because it was the last remaining antibiotic that could be used to treat patients with CRE. Have we seen patients with CRE and colistin resistance? Yes. The strain in the Pennsylvania woman, she was not resistant to carbapenems. Is it bad? Yes, because we’re seeing colistin. And it’s on a plasmid. Could that plasmid get into CRE streams? Absolutely.

So, a little bit of issue related to the headlines: It wasn’t colistin and colistin resistance in a CRE strand of bacteria; there are antibiotics that were still active against her infection. It’s the colistin resistance on that plasmid, meaning eventually we’re going to see it.

Q: Has this come about by overprescribing antibiotics, or people becoming more resistant by having more antibiotics in their systems?

A: Both. Antibiotic stewardship is that basically people demand antibiotics for viral infections, people demand antibiotics for everything, and it’s a matter of not prescribing antibiotics when they’re not needed. We have millions of infections each year that aren’t caused by bacteria but antibiotics are administered. It’s problems associated with the genetic passage of DNA between the organisms; the best way to confer resistance is to pass a little DNA. Exposure of the organisms to antibiotics used in livestock — it’s a combination of all of those things.

Q: That’s true; they’re pumping cows and chickens full of everything.

A: They’re healthier and they’re fatter and they’re bigger and they make more money from the meat.

Q: So it’s not all the fault of doctors? We can lay some of the blame on farmers as well?

A: Farmers and patients. One of the stories I read in the past was a mom or dad who has been dealing with a baby who has been crying for two weeks because they have an ear infection or a viral infection and they’re at their wit’s end and they go in and demand antibiotics. The justification is that it’s a viral infection but maybe that baby will get a secondary infection, so here’s your prescription for antibiotics. Part of it is to get that patient out of the door. They think it’s going to help, and most of the time you ask that mom or dad did it help, and they’re going to say yes. Did it help? Probably not, because it never was a bacterial infection.

But that’s a placebo effect on mom or dad. Eventually the viral infection in children, babies, adults, you’re going to get better over time. It might’ve been that two-week time when it was about to get better and the antibiotics just happened to be available at that given time. That’s a big education point. You hear about it every time it’s in the news: Antibiotics do not work against viral infections. If you have a cold, don’t take an antibiotic. If you have the flu and feel awful, antibiotics won’t work.

Q: So your coach’s old advice wasn’t so bad after all — spit on it and take a lap.

A: That’s right.

Q: What’s going to be a solution? A bigger gun?

A: Inevitably a new drug — a new miracle drug that will generate resistance to it.

Top photo: A closeup of E. coli, which is an example of Enterobacteriaceae, a normal part of the human gut bacteria, that can become carbapenem-resistant. Carbapenems are a class of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

More Health and medicine

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

Arizona State University and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute researchers, along with their collaborators, have discovered a surprising link between a chronic gut infection caused by a common virus and…

ASU, University of Wisconsin partner to empower Black people to quit smoking

Arizona State University faculty at the College of Health Solutions are teaming up with the University of Wisconsin to determine which treatments work best to empower Black people to quit…

New book highlights physician wellness, burnout solutions

Health care professionals dedicate their lives to helping others, but the personal toll of their work often remains hidden.A new book, "Physician Wellness and Resilience: Narrative Prompts to Address…