ASU professor highlights complicated history behind blockbuster 'Roots'

Forty years ago, dozens of young black people lay shackled inside a film set that was made to look like the hold of a slave ship.

They had been hired as extras, portraying Africans who were plucked from their homeland and held captive along with Kunta Kinte, the central character in the blockbuster miniseries “Roots.” To make the scene authentic, the extras were smeared with an oatmeal concoction to simulate the filth of the ship’s hold, where they lay bound for hours.

It was so traumatizing that most did not come back for the next day of filming.

That’s just one of the fascinating details in the upcoming book “Making Roots: A Nation Captivated” by Matthew Delmont, an associate professor of history at Arizona State University in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious StudiesThe School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences..

Delmont, who studies African-American history and popular culture, tackled “Roots” after realizing that there were no book-length studies of the hit story.

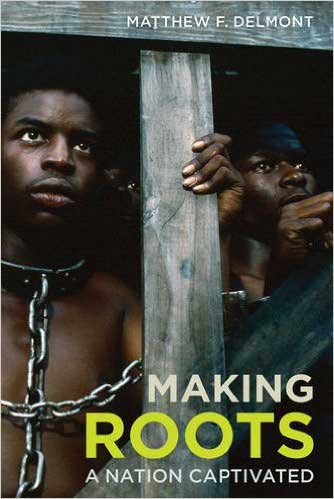

The book cover features LeVar Burton starring as

Kunta Kinte in the 1977 miniseries "Roots."

“It’s kind of amazing because it’s this cultural phenomenon,” said Delmont, who was born almost a year after the eight-part miniseries aired in January 1977.

The TV show was based on the book of the same name written by Alex Haley. Delmont followed the process of Haley’s research and writing (and epic procrastination), the production and reaction to the show and the years afterward, when Haley dealt with accusations of plagiarism and the recognition that the work was partly fiction.

“One of the reasons historians haven’t talked about it is that the relationship between the story of ‘Roots’ and history is messy,” Delmont said. “That’s scared them off.”

Haley set out to tell an amazing story that would be a commercial hit, Delmont said.

“And he achieved that on a scale that almost no one has ever achieved in American popular culture.

“I’m trying to get scholars and popular audiences to come to terms with that and appreciate ‘Roots” as a moment in American popular-culture history, but also to take it seriously as a work of popular history.

“To my mind, if 100 million Americans watched it, ‘Roots’ did more to reshape how ordinary Americans thought about slavery than anything before or since.”

'He wasn't a great writer'

Delmont was able to write the book because he had access to two unusual collections of documents — Haley’s voluminous notes, drafts and letters, and the production notes made during the making of the show.

“Alex Haley sent thousands and thousands of letters to producers and to editors and to fans. You just don’t get that much material that often,” he said.

Because Haley’s estate was in bankruptcy when he died in 1992, his archives were auctioned off. Many papers went to the University of Tennessee, which only recently made them available to historians. Part of the collection was purchased by tiny Goodwin College in Connecticut, where Delmont was among the first scholars to see the documents.

Originally, Haley had no intention of writing about Africa. In 1964, he pitched a book to publishers called “Before This Anger,” about his family’s history in rural Tennessee. Later, after he met a student from Gambia, he decided to expand his story into “Roots,” a generational work reaching from Africa in 1750 to present-day America.

Haley spent a decade talking up “Roots.” He gave dozens of paid lectures around the country, promising a blockbuster long before he got any writing done, Delmont discovered. And he did voluminous research.

“He wasn’t a great writer, but he was a great storyteller,” Delmont said. “He sold ‘Roots’ multiple timesHaley, chronically dogged by financial problems, sold the hardcover and paperback rights as well as an excerpt to Readers Digest. without having a book written.”

In 1974, Haley sold the rights for the TV show, and Delmont believes that Haley never would have finished the book without the deadline of the miniseries — and the $200,000 payment. He turned in the finished manuscript in November 1975, and in 1976, production began on the show.

The production notes were a rare treasure The papers of “Roots” producers David Wolper and Stan Margulies are archived at the University of Southern California. for Delmont.

“One of the challenges of media histories is that usually TV and film producers either don’t keep all that stuff or they leave it to archives. When I was researching my book on 'American Bandstand,'Delmont's previous book is "The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock 'n' Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia." I was buying stuff on eBay and I was interviewing people who danced on the show, but Dick Clark didn’t keep an archive of his materials, or if he did, it’s not available to scholars,” Delmont said.

He speculated that the “Roots” producers knew the show was significant.

“I think they wanted to make their case for their role in television history,” he said. “They kept receipts of how much the actors were paid, the casting schedules, receipts for the Holiday Inn in Savannah.”

Delmont found an amazing story in the documents. The TV executives wanted to ensure that “safe” black actors were cast, including Leslie Uggams, Richard Roundtree and Ben Vereen, and that roles for familiar white actors be created to make the story more relevant to the mostly white viewing audience. The popular Ed Asner played the slave-ship captain.

Delmont’s book describes the distress the actors felt while filming the brutal story. The most iconic scene of the show — when Kunta Kinte is whipped until he speaks his slave name, “Toby” — was harrowing emotionally and physically for the young actor LeVar Burton, who later said he remembered little of it. The filming was postponed for a few days until Burton could work with the stunt expert who handled the whip to make sure he wouldn’t actually be injured.

But the young people who were extras in the slave-ship scene, many of whom were students from Savannah State College, were treated less sensitively, Delmont said.

“The producers didn’t really give that any thought, which is kind of remarkable,” he said.

“They were interested in how they would light the scene and how they would make this a viscerally powerful moment in American television. But they didn’t think, ‘What does this mean to ask an 18-year-old African-American who isn’t a professional actor to lay in this representation of a slave ship for three or four hours?’

“It wasn’t any ordinary acting job.”

They were paid $30 a day.

The remade "Roots" miniseries — which will air simultaneously on the A&E, History and Lifetime channels May 30 through June 2 — boasts higher production values than the original, which may help draw in younger audiences. Photo by History Channel

Casting doubt

By the time the show aired in January 1977, the book had sold a million copies. Haley always said his book would be “faction” — a combination of fact and fiction. But the ABC network and the book publishers insisted the work was non-fiction.

“Roots” became the most-watched TV show in history, and many black viewers were inspired by the direct family link back to Africa. Yet that part of Haley’s work was unable to withstand scrutiny by journalists and academics. Further research on genealogies and slave-ship and property records cast doubt on details in his story.

Years later, Haley settled two lawsuits that accused him of plagiarizing portions of “Roots.”

Delmont said that likely happened because Haley was not a trained historian and relied heavily on a research assistant.

“Haley didn’t know the rigorous processes of footnoting and keeping track of your sources — which doesn’t let him off the hook,” Delmont said.

“He was clear about issues of copyright. One of the things I found most frustrating was that he should have known better.”

Delmont has seen the four parts of the new “Roots” and will be supplying commentary on the Mother Jones website after each episode.

“They’ve done a nice job. The production values are a lot higher than in the 1970s,” he said.

“I like the 1970s version, but I know when I’ve shown it to students, it’s hard for them to get past ‘this looks like it was in the 1970s’ and appreciate what it was doing,” he said.

Delmont believes the controversies of the original shouldn't detract from its importance in popular culture, but that the timing is right for a new “Roots.”

“Slavery is being discussed now with renewed urgency, and you have the naming controversies, and the reckoning with the fact that many institutions have been funded with money from slavery,” he said.

“People are talking about slavery in a way they haven’t been, and this can be part of that conversation.”

More Arts, humanities and education

From ASU to the open road: Alumna Gabriella Shead builds a career behind the scenes of Broadway tours

For ASU alumna Gabriella Shead, a career in the theater isn’t about taking center stage — it’s about making sure everything behind the curtain runs seamlessly. Now serving as assistant company…

Canon brings ‘Star Wars’ cinematographer to inspire Poitier Film School students

David Klein never had a mentor.He was scrappy — and lucky — enough to succeed without one as a career cinematographer. His first feature film was the no-frills, DIY darling of ‘90s indie cinema…

Illuminating the season: How a business professor turns holiday lights into lessons on creativity and sustainability

On a December night in Chandler, Arizona, Kevin Dooley’s house doesn’t just twinkle. It beams like a beacon at the end of the cul-de-sac as the windows shimmer with color, and every corner…