Editor’s note: HealthTell recently completed a $40 million capital campaign. The company, a spinout of ASU's Biodesign Institute with a nearby manufacturing facility in Chandler, Arizona, is poised to enter the big leagues as “one of the top five start-ups to watch” in the highly competitive health-care diagnostics arena. Here's how they're looking to change how we approach disease.

Almost one out of every five dollars in the U.S. economy is spent on health care.

Despite spending far more on health care than any other country, Americans have gotten a poor return on their investment, ranking middle of the pack worldwide for metrics such as infant mortality rates and longevity.

Two Arizona State University researchers had an idea that could radically change the way we approach health care, a fresh take on Benjamin Franklin’s well-worn adage: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

What if we could detect disease at its earliest stages, perhaps even before symptoms appear? This would allow health-care providers to address problems before serious — perhaps irreversible — damage has occurred, with better outcomes and lower costs.

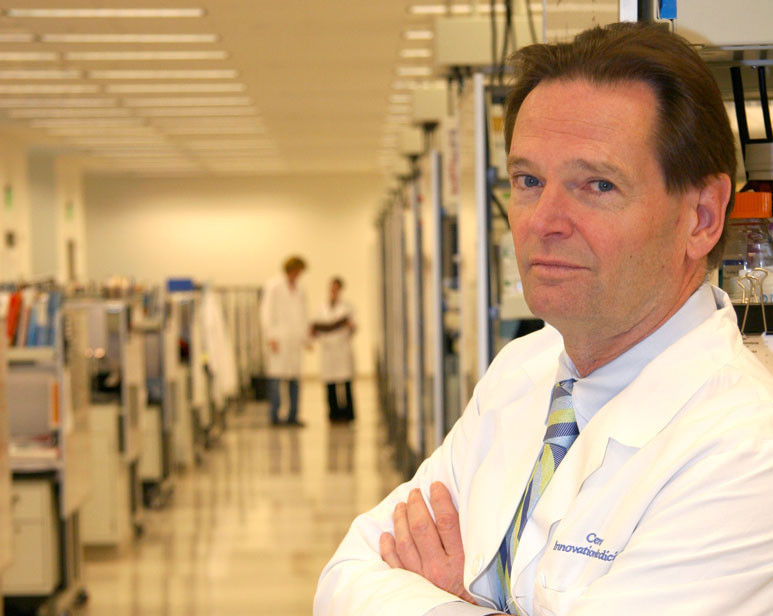

“The idea was to change medicine from post-symptomatic to pre-symptomatic. To do that, you have to monitor healthy people and figure out what’s happening early to them,” said Stephen Albert Johnston, director of the Center for Innovations in Medicine at ASU’s Biodesign Institute.

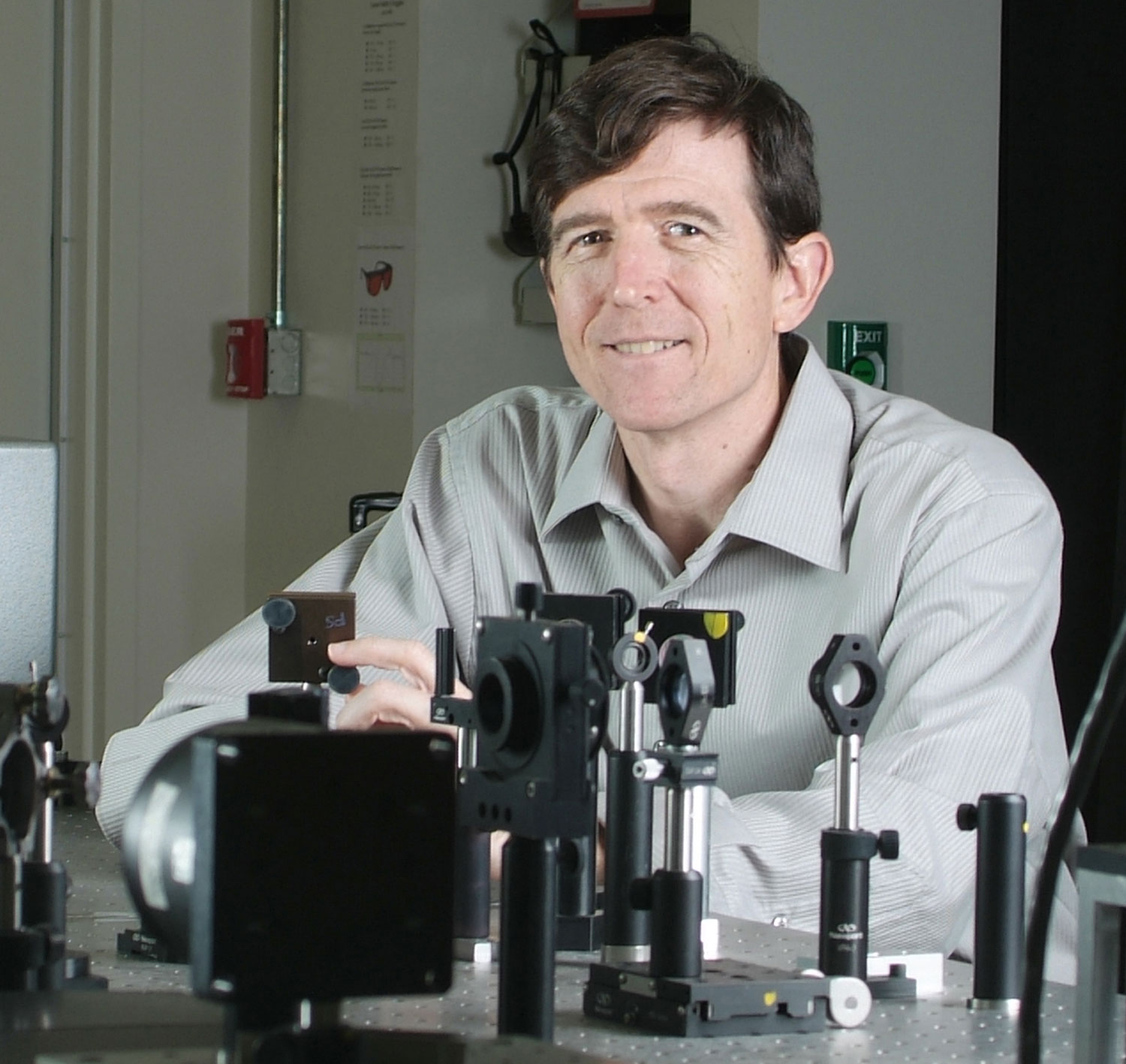

In 2005, Johnston teamed up with Neal Woodbury, an ASU chemistry professor, to pursue this goal.

“We spent a long time to try to come up with an invention that could do that sort of thing. And it had to be cheap. Because if it’s too expensive, people won’t use it, and people in the developing world would never use it,” Johnston said.

The like-minded mavericks were in the right place to cultivate their ideas. In 2002, ASU President Michael Crow first conceived a new approach to science, the Biodesign Institute. His vision was simple but bold: Throw out the traditional academic silos between disciplines and bring together leading biologists, engineers and computational science experts under one roof in order to nurture paradigm-shifting advances inspired by nature.

“We spent a long time to try to come up with an invention that could do that sort of thing. And it had to be cheap. Because if it’s too expensive, people won’t use it, and people in the developing world would never use it.”

— Stephen Albert Johnston, director of the Center for Innovations in Medicine at ASU’s Biodesign Institute

Woodbury was among the first scientists recruited to the new institute. He had been at ASU since 1987, studying the early events of photosynthesis, the process through which plants convert sunlight into fuel. He had seen firsthand the benefits of an interdisciplinary approach to science, working with a 20-faculty-member team toward unraveling the exact chain of events that occurs in those first trillionths of a second when light powers photosynthesis.

For his next endeavor, Woodbury wanted to contribute to the area of chemical spaces and biological information.

“If you look at the chemistry of biological systems, we actually generate a huge amount of diversity in what life can do from a relatively simple group of building-block chemicals. They are strung together to make proteins, to make DNA, to give rise to much of the diversity of life,” he said.

Johnston came to ASU to establish the Biodesign Institute’s Center for Innovations in Medicine. He relishes the outlaw role of the scientific disruptor and fit in seamlessly to Biodesign’s “Wild West” culture.

Johnston came up with the idea that would lead to the spinout company HealthTell before he came to ASU. But the Biodesign Institute, with its mix of expertise and a culture that encouraged researchers to try anything, was the ideal environment to bring that idea to fruition.

Johnston and Woodbury’s work was fueled by support from the Arizona voter-approved Technology and Research Initiative Fund (TRIF), derived from a percentage of sales-tax revenues. TRIF support has been critical as a seed-funding base, enabling scientists to perform early-stage, high-risk, high-reward research that can be leveraged into larger funding opportunities.

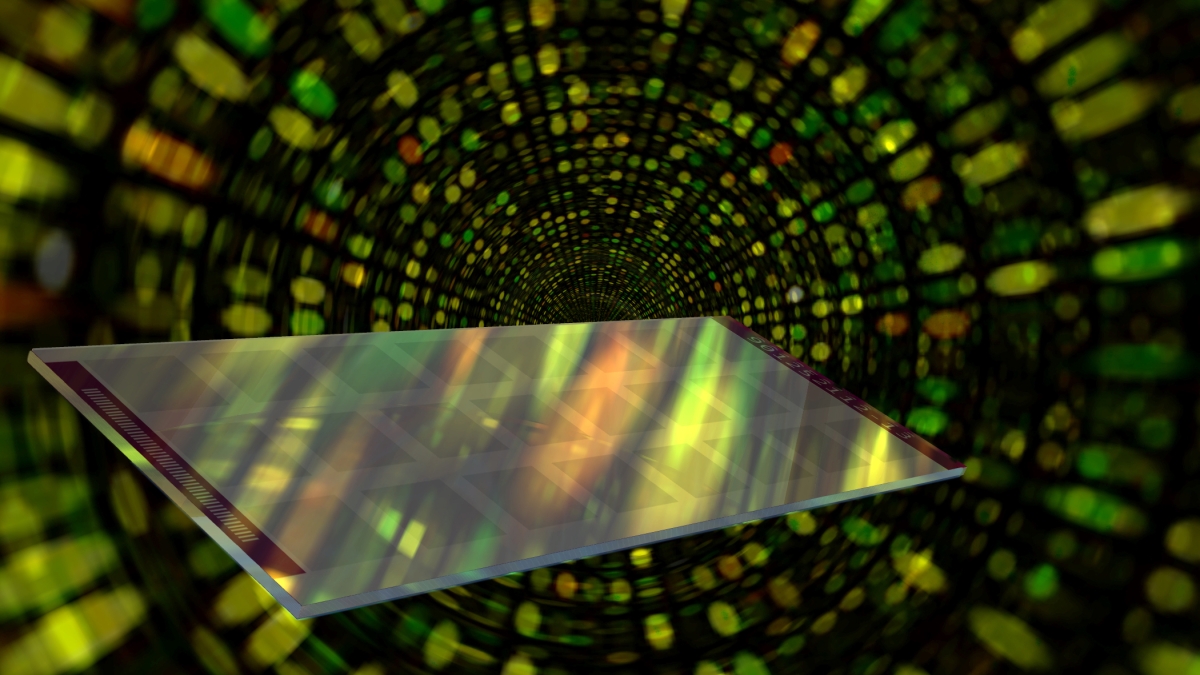

Neal Woodbury, co-founder of HealthTell, was among the first scientists recruited to the new Biodesign Institute at ASU. Top image: Each immunosignature slide has 24 arrays on each one. They are printed on 3-by-8 rows, 24 assays per slide, with each array holding 130,000 peptides on it.

A new frontier

Their idea centered around a huge, untapped natural resource found in every person: the immune system.

“I finally came upon this really simple concept,” said Johnston, also a professor in the School of Life Sciences in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “And that was, you have millions, billions of antibodies in your body. And if those antibodies were always registering your health status, and we had a way to look at that whole repertoire, to get a signature of your antibodies, and do so in a simple way, we might be able to revolutionize diagnostics.”

Some of the leading causes of death — both infectious and chronic diseases like cancer — give rise to immune responses fairly early in the course of disease. If Johnston and Woodbury were right, simply taking a snapshot of the immune system could provide an in-depth picture of a person’s health.

The challenge would be to measure this antibody diversity in a single drop of blood or in saliva. The team drew inspiration from the computer industry, which uses silicon-wafer technology for ever-faster and cheaper computer chips.

“The technical problem was how to make these peptide arrays. We knew that if we could display on a small number of peptides from random space, we could develop what we called an ‘immunosignature’ of disease,” Johnston said.

For the first test, in 2006, they contracted with a company called LC Sciences to place 4,000 short pieces of protein, called peptides, in neatly arranged 10-micron (a millionth of an inch) rows on a microscope-sized glass slide.

Next, they took blood serum from a test subject and control to see the differences between the two.

“I have to be honest, after those first arrays, I didn’t believe much of any of it,” said Woodbury, a professor of biochemistry and chemistry. “I thought, ‘This looks like it could be anything to me.’ You see a difference in a few peptides out of a thousand, and you say to yourself, ‘I don’t know.’”

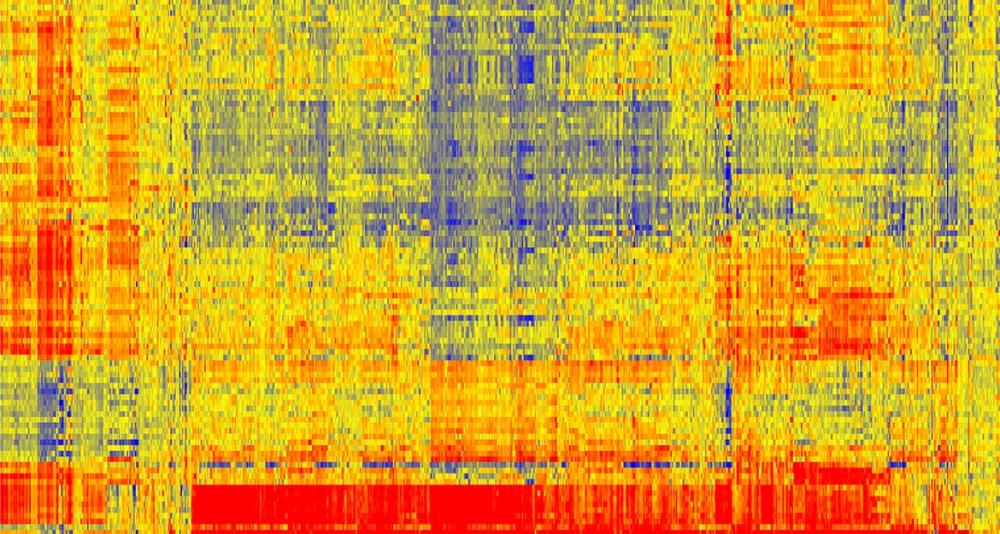

The initial picture looked like a random bunch of multicolored dots on a Lite-Brite toy. One sees different signals with different dots, depending on where the antibodies are binding on the slide. The beauty of the innovation is that there is not a specific antibody for a specific disease, but rather a whole picture, or signature, of disease.

“I give Stephen a huge amount of credit for this. He first thought the signal was real and we should pursue it, and was willing to back it all the way to the bank,” Woodbury said. “Eventually, I agreed with him, but had it just been me, I probably would have said, ‘It’s not enough.’”

In fact, differences between the healthy and control sample in just two spots out of the 4,000 peptides on the array convinced Johnston to forge ahead.

“The key was that peptides were from random space — not disease specific,” Johnston said. “No one thought antibodies would bind to these peptides, let alone be informative.”

To get an immunosignature, a single drop of blood, containing an individual’s complete set of antibodies, is spread across a glass-slide array of 10,000 random sequence peptides, imprinted on a microarray slide. The immune system’s complete pattern of activity is seen after exposure to a pathogen, a vaccine or any other factor provoking a change in the antibody portrait. A chemical marker causes an antigen-antibody pair to fluoresce, with the magnitude of fluorescence indicating the strength of antigen-antibody binding (red is strong binding, blue is weak).

True grit

Fostering a biotech start-up is not for the faint of heart. “We went out and made investments based on our early success that no federal funding agency would have considered,” Woodbury said.

Their boldness and willingness to forge ahead in the face of adversity was recently recognized by National Science Foundation director France A. Cordova, who learned firsthand of their efforts during her visit to ASU last year. She was given a parting gift, an immunosignature array slide.

Cordova highlighted the promise the technology holds for personalized medicine during a recent interview.

“I have in front of me a little peptide array — in Plexiglas, so I can’t use it — developed at ASU’s Biodesign Institute. You put different blood drops in and they can read immunosignatures to tell if you have one of five different types of cancer. I asked the lead investigator, 'Did you apply to NIH for funding?' They said it was too high‑risk. Instead, we funded it. A lot of what we fund is considered 'high‑risk, high-reward': People don’t know what the outcome will be or where the research will go. But fundamental science enables the kinds of breakthroughs that drive the economy," she said.

Early-stage, high-risk research can be mired in issues of reproducibility and validation. To confront these challenges, Woodbury and Johnston assembled a posse of pros, including bioinformatics expert Phillip Stafford (who holds a co-patent on the technology for spearheading the interpretation of the data), immunologist Kathryn Sykes, and chemists Bart Legutki, Chris Diehnelt, Zhan-gong Zhao and others.

Each member’s expertise was essential to continuing the momentum of the project, expanding the prognostic power of the technology while working out the bugs in the chemistry and costs.

Just to enter into the highly competitive diagnostics marketplace, they needed to reduce the costs to $100 a test. And to enhance diagnostic power, they needed to pack more peptides onto ever-denser arrays, first 10,000, then 100,000, to now, 350,000 peptides on a single chip.

“The trick was to splay these peptides out cheaply, so we went to an Intel type of manufacturing. We had a number of ideas to work through, and spent about 10 years working on our platform for making the peptide arrays,” Johnston said.

This critical stage, leaping from proof-of-concept to spinout, is often referred to as the “Valley of Death” for tech start-ups.

“We put the money up initially ourselves to start HealthTell,” Johnston said. “We received some good federal contracts with the Department of Defense initially, and then we brought in a CEO, and have steadily grown the company to the point where we are on the brink of commercialization.”

CEO Bill Colston, a Silicon Valley start-up veteran, was attracted to joining HealthTell because of a unique opportunity in the Valley of the Sun.

“First off, the genetic space is pretty crowded, with dozens of new DNA-testing companies,” he said. “And there is only so much information to get from genetics. I’ve been interested in getting closer to where the action is, the immune system. For the first time, we can use millions of years of evolution in the immune system and leverage that biology in a more universal way. I think you are starting to see that shift with cancer.”

HealthTell now employs about 35 people in Chandler, Arizona. Initially, it relied on critical government contracts to fund manufacturing of the chips locally. Since then, Colston has been raising additional capital for HealthTell, with $26 million to date, according to a recent regulatory filing, on top of the initial $14 million A series round of investment in February of 2014. The company will expand the number of employees to 70 and release its first product by 2017.

A scientific gunslinger (he co-invented the gene gun and was recruited to ASU from Texas), Stephen Albert Johnston relishes the outlaw role of the scientific disruptor.

Fast-draw diagnosis

For HealthTell’s tests, only a single microliter — or 1/20 of a drop — of blood is needed. This is spotted onto a piece of filter paper and dropped off in the mail. At HealthTell, the blood is diluted and put on a piece of a silicon wafer.

“The chip is agnostic,” Johnston said. “It just binds to any antibody. Any antibody you put on there will have its own distinctive pattern.”

The same chip can be used for all diseases in all species. It detects any type of antibody. There is no sample preparation. You can use samples up to 20 years old. And it is 10 to 100 times more sensitive than a standard tests on the market, such as ELISA.

“When they hear about the technology, most people have the same response,” Johnston said. “‘This can’t be true. It’s too simple to be true.’ But I assure you it’s true. The signature is reproducible and informative.”

To date, HealthTell has been able to identify Valley Fever and outperform the best diagnostic test on the market. They can distinguish between 15 different diseases simultaneously, including Alzheimer’s disease, and have tested it on more than 1,500 individuals with 95 percent accuracy.

For the past several years, HealthTell has focused on improving the performance and reproducibility of the chips.

“We are getting great results,” Colston said. “We have two major business lines, a pipeline for pharmaceutical customers that pay us for developing tests for them to make drugs more effective, and the second is a diagnostic program in partnership with physicians for the early detection of infectious disease, cancer and autoimmune disorders.”

The pharmaceutical services are designed to fill in the gap in the early years of HealthTell as the future of its commercial diagnostics marketplace takes shape. Recently, the company has been testing a new class of cancer drugs that turn off pieces of immune system inhibitors known as checkpoint inhibitors.

“These are very effective but only work on 20 percent of the patients,” Colston said. “One of the clinical trials better informs physicians on how the drugs are working, and we have several more underway.”

One goal is to set up a central lab within HealthTell to handle processing of samples mailed in from consumers. One of the first areas for consumer diagnostics testing will be for better detection of autoimmune disorders such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

HealthTell has garnered its fair share of attention. It was named the Arizona Governor’s Celebration of Innovation as “Start-up of the Year” in 2012, and more recently by Silicon Valley, as one of the “top five start-ups to watch.”

“It’s taken a long time, but it’s getting there. There is really no other technology like this out there,” Johnston said.

“It’s time to start putting some of those diseases in the rear view mirror,” added Woodbury. “We would really like to put cancer in the rear-view mirror or get it to where it’s manageable. The best way to get it to where it’s manageable is to see it earlier.”

More than 80 start-up companies have launched based on ASU innovations. Learn more about how AzTE, ASU's exclusive technology transfer organization, supports viable start-ups like HealthTell.

More Science and technology

Brilliant move: Mathematician’s latest gambit is new chess AI

Benjamin Franklin wrote a book about chess. Napoleon spent his post-Waterloo years in exile playing the game on St. Helena. John Wayne carried a set and played during downtime while filming “El…

ASU team studying radiation-resistant stem cells that could protect astronauts in space

It’s 2038.A group of NASA astronauts headed for Mars on a six-month scientific mission carry with them personalized stem cell banks. The stem cells can be injected to help ward off the effects of…

Largest genetic chimpanzee study unveils how they’ve adapted to multiple habitats and disease

Chimpanzees are humans' closest living relatives, sharing about 98% of our DNA. Because of this, scientists can learn more about human evolution by studying how chimpanzees adapt to different…