Sometimes you get the party started by accidentally crashing someone else’s.

Mark Robinson, a professor in Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space ExplorationThe School of Earth and Space Exploration is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences., was enjoying a First Fridays art walk in downtown Phoenix during the summer of 2012 when he wandered into monOrchid gallery on Roosevelt. Only the gallery wasn’t open to the public that evening.

“I realized I had just crashed someone’s private party,” Robinson said.

He spoke with someone on the edge of the crowd, who turned out to be the gallery’s owner. Robinson — principal investigator for the ASU-operated cameras aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) — introduced himself and the mission’s photographs, saying he thought they’d make for a great exhibit.

“He was polite, but I think he kind of thought I was … kind of wacko,” Robinson said.

But when he brought in photographs to show the owner and unrolled a 12-foot-long, high-res version of the Tycho crater’s central peak, Robinson recalled, “All he said was, ‘Do you want to do this in October or November?’ ”

That exhibit, which drew thousands of visitors, was the first step on a journey leading to this Friday’s opening of “A New Moon Rises,” an exhibit of 61 images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Robinson hopes it gets people excited about the moon again, in an age when many eyes are turned toward Mars and the thought of manned flights there.

“The moon is this beautiful little world,” Robinson said. “It’s not just a romantic silver disc you see in the sky at night; it’s a world in its own right. And it’s somewhere we should be going back to.”

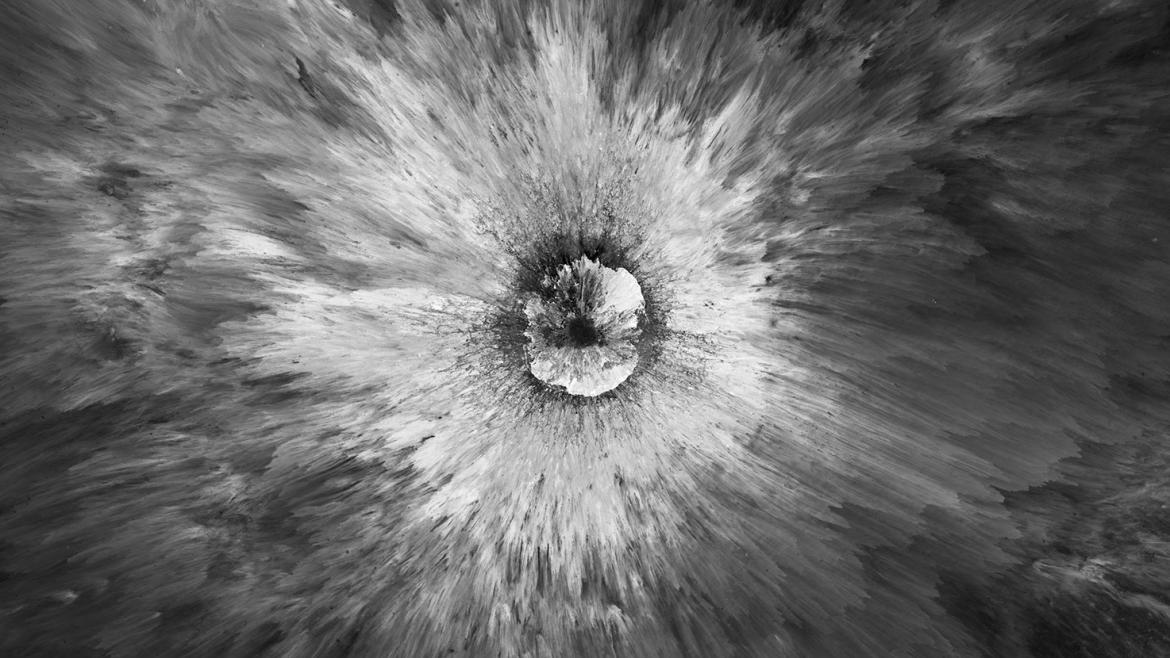

Though it might appear a bit like the Eye of Sauron, this LROC image is of a small crater on the rim of Chaplygin crater.

Photo by NASA/GSFC/ Arizona State University

The LROC’s thousands of images — curated on the team’s website — are often a blend of science and artistry. Tom Watters, senior scientist at the museum’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies and curator of the exhibit, said one of goals of the Smithsonian event is to “captivate the visitor with the sheer beauty of the landscape of the moon.”

“If it’s lit in a certain way from the high sun angles, you get these wonderful variations in the brightness of the materials, and those can be very surreal-looking,” Watters said. “And if you have the dusk-to-dawn lighting, with the low sun angles with the shadows being cast, the incredible details in the landscape come out.”

He credits all those on the LRO team — the sheer amount of work involved often isn’t obvious to the general public — but said Robinson deserves a large portion of that praise.

“If it wouldn’t embarrass him, he really is the Rembrandt of capturing just the right kind of lighting,” Watters said. “He’s the maestro, the master of doing that.”

The artistry makes sense with Robinson’s background — he didn’t originally intend a career in space. His first college degree was a double major in political science and fine-art photography.

But luckily for the scientific community, that original career path didn’t result in any real jobs. “I was always interested in science,” he said. “… I somehow got into college and did the wrong thing.”

A chance conversation with a friend at a summer construction job led Robinson to Alaska, where he worked with geologists and discovered the field that would take him, metaphorically at least, into the heavens.

ASU professor Mark Robinson in the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Science Operations Center, on the ASU Tempe campus. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

His association with the Smithsonian goes back decades, but this is his first exhibit there.

“My hope is that we’re going to get millions of people — maybe I’m being a little optimistic — totally excited about the moon,” Robinson said. “The moon will be a new place. They will realize the moon is a magnificent world in its own right. It’s a world in change right now.”

More than 200 new craters have been imaged since the LRO started orbiting, Robinson said. Another surprise to scientists has been evidence of very young volcanism there, changing the previously assumed timeline that lunar volcanism ended 1 billion to 2 billion years ago.

“It really transforms the moon in my mind,” Watters said. “ … The moon is still alive. There’s still a lot going on there. It’s not a dead object at all.”

The LRO cameras, which were fabricated by Malin Space Science Systems, send back 450 gigabits (about 56 gigabytes) of science data every day and have been doing so for six and a half years. It’s more than all other NASA planetary missions throughout history combined, Robinson said.

About 90 percent of the data flow is automated, both the uplink and the processing. “We couldn’t keep up with it otherwise. It would be like trying to catch Niagara Falls with a 5-gallon bucket,” he said.

Even with that automation, it takes a team of 30 people, including about a dozen undergraduate students, to keep the project humming. Each image must be planned — not only the location for visual or scientific purposes and what the lighting will be, but even down to what the temperature will be at the moment the image is captured, as that can affect other components. The oblique images’ composition especially receives an extra level of review.

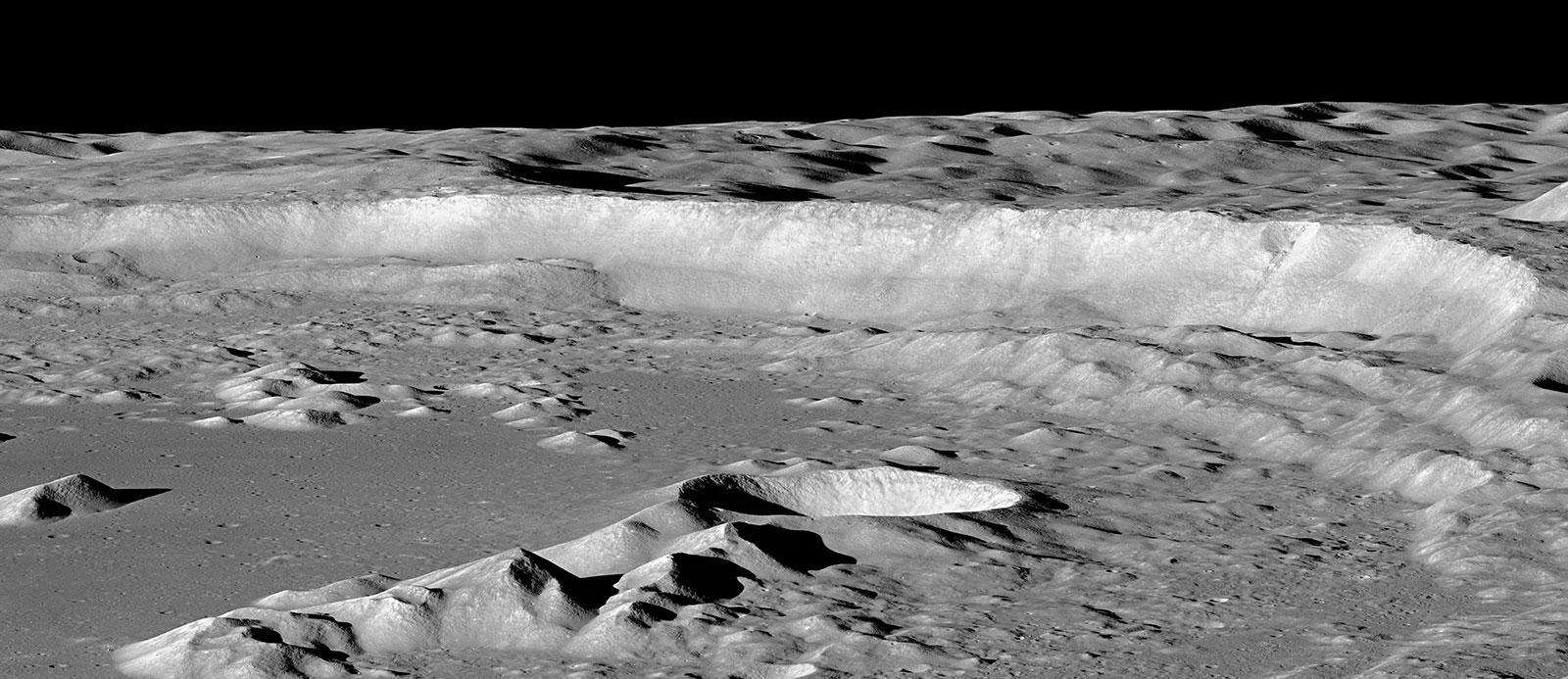

In this oblique view, the 4,000-meter-tall cliff in the background is the east wall of Antoniadi crater, which is 140 kilometers in diameter. The bottom of the small bowl-shaped crater tucked behind peaks in the center ground is the lowest point on the moon, more than 9 kilometers below the mean radius (comparable to sea level on Earth). Photo by NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The images are incredibly crisp, especially considering that the spacecraft is moving at 1,600 meters per second — more than 3,500 miles per hour. The team needed an effective exposure time of 0.3 milliseconds, three times shorter than the fastest of cameras available.

They achieved that, and the result is photographs of incredible depth and variation in tone. Shadows and highlights reveal detail, and some of the images appear more like modern art than science resource.

The exhibit, which will run at least through December, will include a state-of-the-art laser projector showing the latest LROC images, a large 3-D model of a lunar crater and an interactive kiosk that allows visitors to explore more of the LROC data. A similar one stands in the visitor center in Interdisciplinary A on the Tempe campus.

Robinson hopes the beauty of the images draws visitors in, and that the delight in seeing LROC images that show the human and rover tracks from Apollo missions sparks questions as to why we aren’t returning there.

“How do you really top human beings for the first time walking on another world?” Robinson said. “But now that’s 47 years ago. It’s time to go back in a different manner, a more measured manner. …

“The time is right now to start heading back, not to plant a flag and pick up a few rocks, but this time for sustained exploration and sustained science. And that will enable us to go to Mars and even farther out into the solar system.”

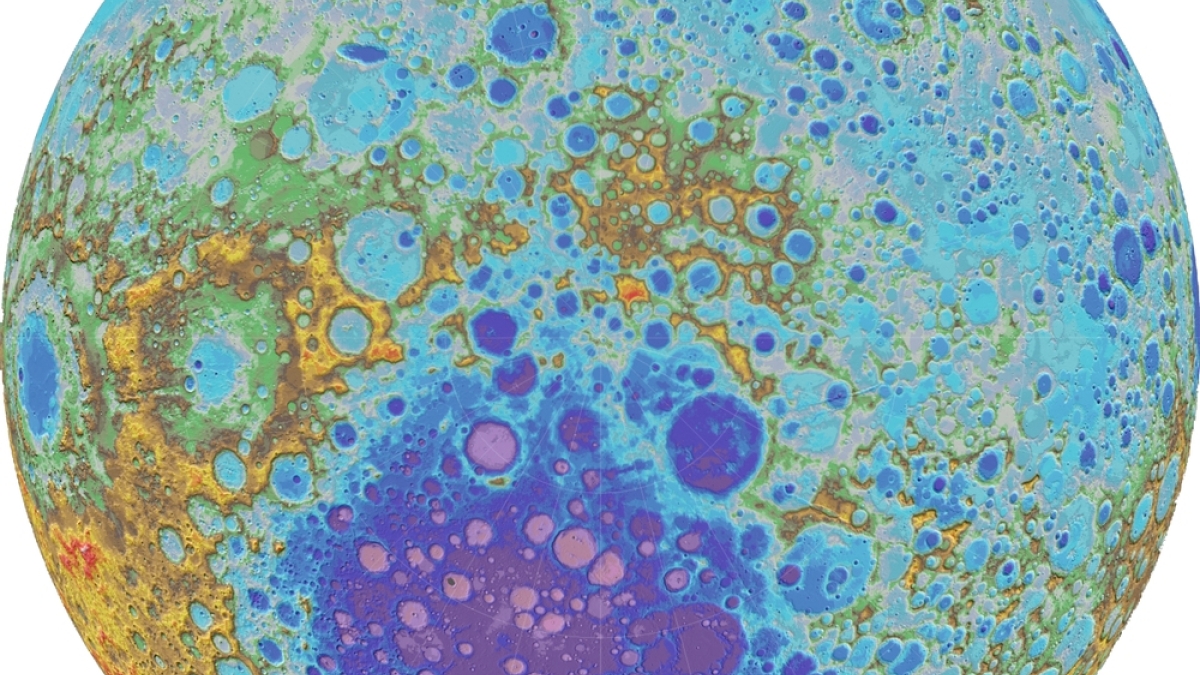

Top photo: In this view of the moon, the South Pole is at the center. The colors represent different elevations. The large, roughly circular, low-lying area (deep blue and purple) is the South Pole–Aitken Basin, the largest and deepest impact feature on the moon. Photo by NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

More Science and technology

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable social relationships. There are tons of such clubs on ASU's campuses…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as designing the future. The consortium marked 25 years in Washington, D…

Hacking satellites to fix our oceans and shoot for the stars

By Preesha KumarFrom memory foam mattresses to the camera and GPS navigation on our phones, technology that was developed for space applications enhances our everyday lives on Earth. In fact, Chris…