News broke this week that a planet 10 times the size of Earth may be lurking at the edge of our solar system.

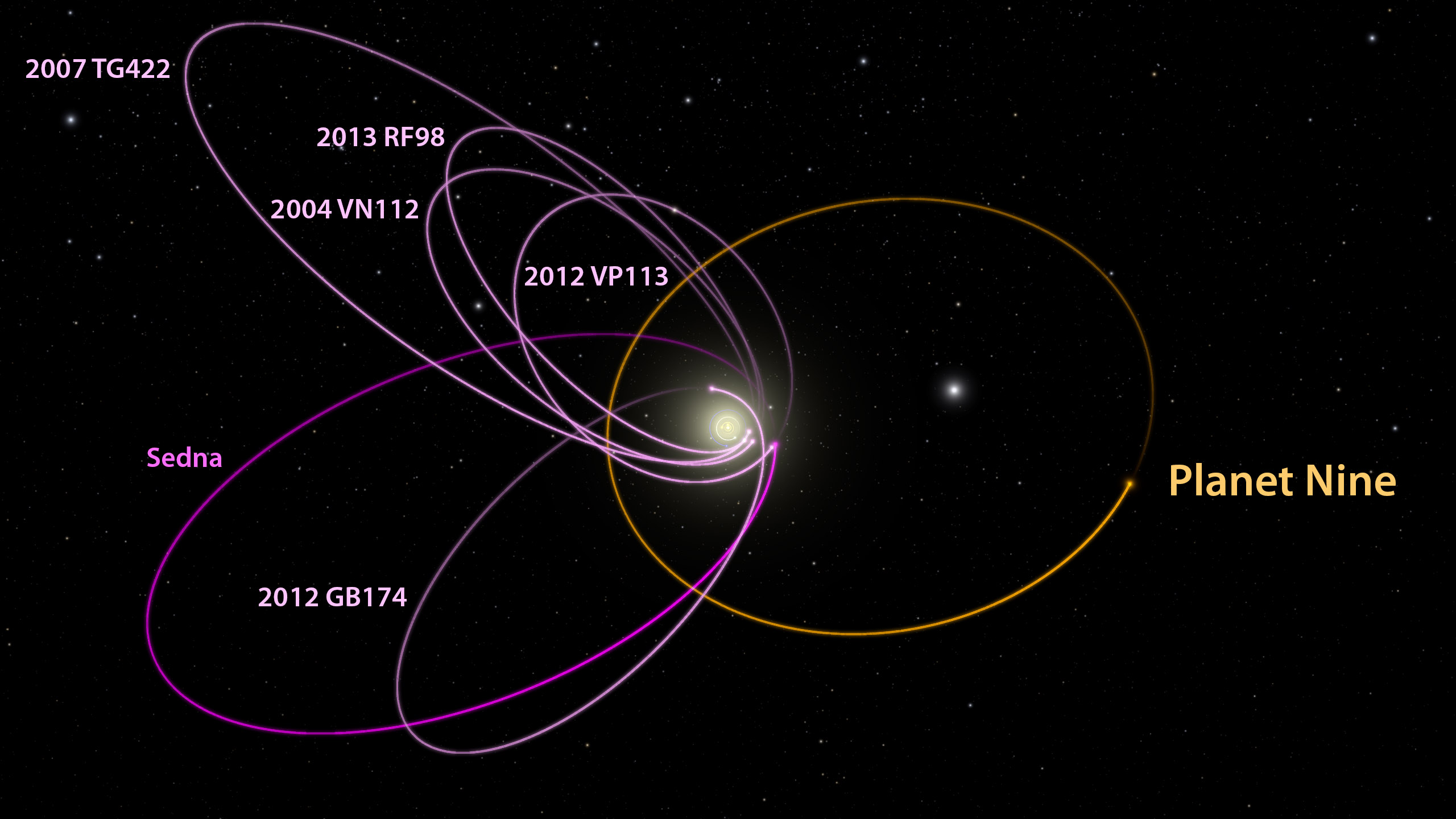

Researchers at Caltech nicknamed it Planet Nine and estimated it orbits about 20 times farther from the sun than Neptune. Scientists did not actually observe the planet; mathematical modeling and computer simulation led them to hypothesize a planet was exerting the gravity necessary to cause objects in the Kuiper Belt to orbit in the same direction.

Theoretical astrophysicist Patrick Young, an associate professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration The School of Earth and Space Exploration is a unit of ASU's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.at Arizona State University, spoke with ASU Now about the significance of the announcement.

Question: How is it that this object hasn’t been seen before?

Answer: The idea is that if it exists, it’s a very distant object and it’s emitting very little radiation of its own. It’s not going to be reflecting much from the sun at this distance, so it’s not an easy thing to see. You would have to have an idea it’s there and do a lot of work to find it. It’s not something you would necessarily notice offhand. This is definitely not a discovery, and judging from the authors’ publication, I think they would agree with that. It’s merely suggested that it’s worth doing those difficult observations to see if we can find something.

Q: You said it’s difficult to observe. Why can’t we see it with Kepler or Hubble, something that can peer deep, deep into space?

A: If we knew where to look, we could almost certainly see it with Hubble. The issue is that it’s going to be in a very tiny part of the sky and Hubble does not observe very large areas. It only observes something much less than the size of the full moon at a time, so you really have to be pointed in the right direction. Kepler is designed to do a very different thing. It points at one very tiny region of the sky and monitors that continuously. That is not in a direction this object would be, if it exists.

Q: So there’s a lot of universe out there and it’s big enough to hide something 10 times the size of Earth?

A: Yes. When you figure that this thing is tens of billions of miles away from the sun at least, and if it’s a few times the size of Earth — tens of thousands of miles across — you can see that’s a tiny dot in a big area. It’s a lot of needles in haystacks.

The six most distant known objects in the solar system with orbits exclusively beyond Neptune (magenta) cluster in a single direction. Such an arrangement would be maintained by an outside force. Caltech researchers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown show in a new paper that a planet with 10 times the mass of Earth in a distant orbit anti-aligned with the other six objects (orange) is required to maintain this configuration. Top: An artist representation of Planet Nine, believed to be gaseous, similar to Uranus and Neptune. Images courtesy of R. Hurt/Caltech

Q: But so far it’s theoretical?

A: Right. Essentially what’s going on is this group has looked at the orbits of small bodies in the outer solar system — what we call Kuiper Belt objects — and they have noticed that the orbits of a certain class of these typified by Sedna, which is one of these dwarf planets that ended up getting Pluto demoted, are clustered in a certain area of orbital parameters, so they have fairly similar kinds of orbits that actually cluster very roughly in space. There are a few ways of making orbits cluster like this, and it turns out the work they have done shows that having a planet 10 or so Earth masses out at these large distances could very well cause that clustering in a plausible way. The other options for making those orbits look that way are not significantly more probable. Those all have problems describing things.

Q: Would it be accurate to say despite this week’s headlines that this is less than earthshaking in the world of planetary science and astronomy?

A: I would agree with that. It’s a very interesting result, but I wouldn’t call it a discovery until we actually make an observation of the planet.

Q: So this is more a function of people wanting to replace Pluto than anything else?

A: (laughs) I think that the first author of this paper, who takes credit for killing Pluto, would say that we don’t need to replace it, that it had it coming. But I think that generates a lot of the excitement about it.

See a video version of the interview below.

More Science and technology

Astronomers observe ultra-hot nova with unexpected chemistry

A team of astronomers, including Arizona State University Regents Professor Sumner Starrfield, has uncovered an exceptionally hot and violent eruption through the first-ever near-infrared analysis of…

Statewide initiative to speed transfer of ASU lab research to marketplace

A new initiative will help speed the time it takes for groundbreaking biomedical research at Arizona’s three public universities to be transformed into devices, drugs and therapies that help people.…

ASU research seeks solutions to challenges faced by middle-aged adults

Adults in midlife comprise a large percentage of the country’s population — 24 percent of Arizonans are between 45 and 65 years old — and they also make up the majority of the American workforce…