Carlos Velez-Ibanez desires to know two things: 1) How are people able to excel when they shouldn’t be able to? and 2) How are people able to survive when they shouldn’t be able to?

They’re questions that carry a lot of weight and whose answers he asserts have “enormous implications” for understanding and appreciating humanity, with all its mysteries and nuances.

So for the better part of four decades, the Arizona State University Regents’ ProfessorCarlos Velez-Ibanez serves as a Regents' Professor in the School of Transborder Studies as well as the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, both academic units of ASU’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Velez-Ibanez is also a Presidential Motorola Professor of Neighborhood Revitalization. has made it his mission to uncover those answers, conducting interdisciplinary anthropological research on subjects such as migration, economic stratification and political ecology in the U.S.-Mexico border region of what he calls “Southwest North America.”

Now, his years of passionate inquiry are being recognized by the Mexican Academy of Sciences, which has named him a corresponding member. A high distinction in itself, the recognition is all the more prestigious for Velez-Ibanez, a Tucson native and the first American anthropologist to receive it — and it came as quite the surprise.

“[My colleagues] had been asking me for material and I didn’t know what it was for until I got the notification. I thought they were putting a research project together or some kind of invitation to give a lecture,” he said.

As it turned out, the four colleagues who had been requesting scholarly material from him were using it to nominate him to the academy. They include: Mariangela Rodriguez, researcher and professor at the Centro de Estudios Superiores en Antropologia (CIESAS)The Center for Research and Studies in Social Anthropology; Rodolfo Stavenhagen, one of Mexico’s premier sociologists; Tonatiuh Guillen Lopez, director of Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF)The College of the Northern Border; and Jose Manuel Valenzeula Arce, academic provost for COLEF.

All four of Velez-Ibanez’s nominators are also prominent members of the Mexican Academy of Sciences, a civil organization comprising more than 1,800 distinguished Mexican scientists from various institutions in the country, as well as a number of foreign colleagues, including various Nobel Prize winners — “which ain’t bad company,” Velez-Ibanez notes with a smile.

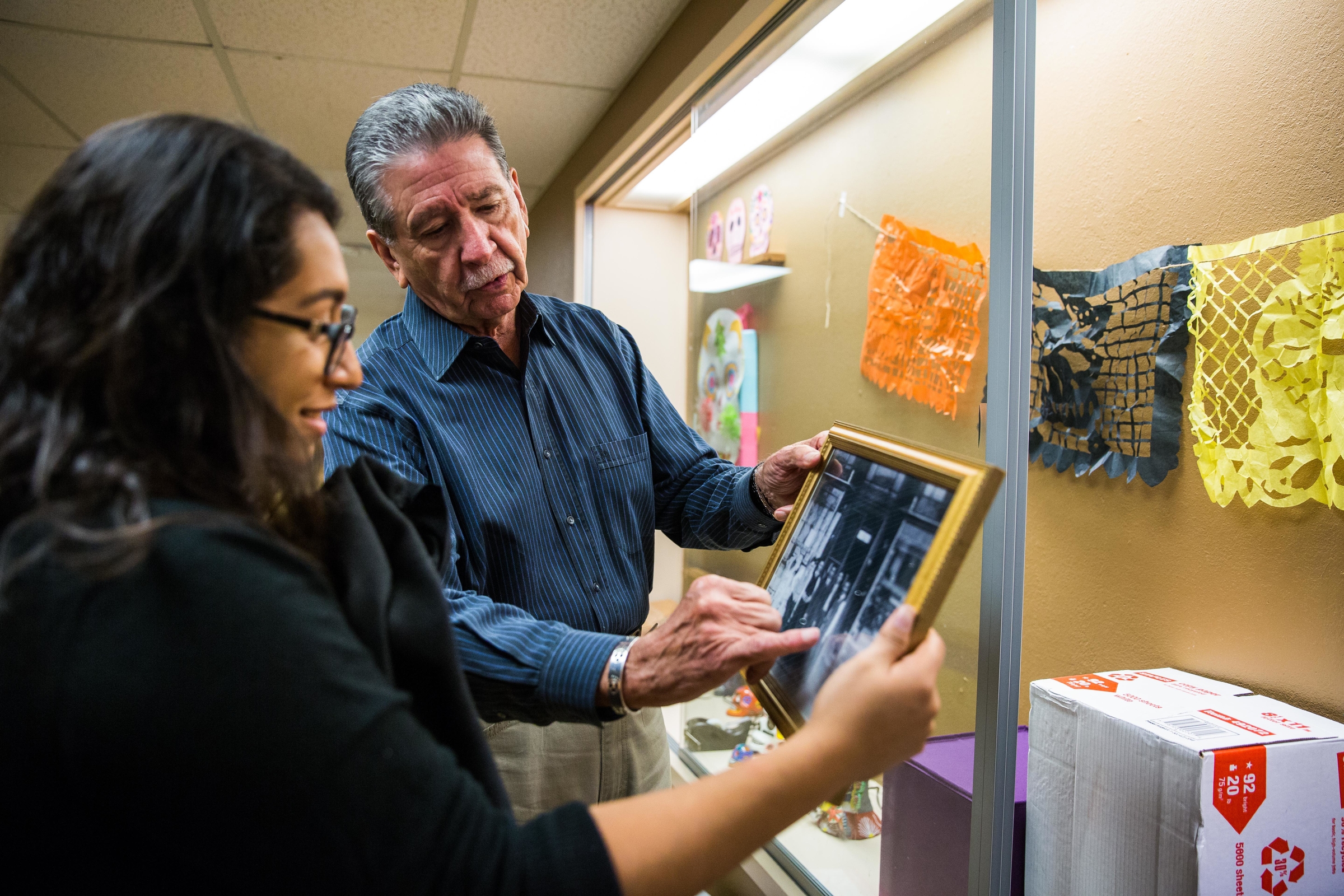

Carlos Velez-Ibanez speaks with a student, freshman business law major Aline Francisco Lewis, in his office at the School for Transborder Studies. Velez-Ibanez was recently named to the Mexican Academy of Sciences, making him the first American anthropologist to do so. Photos by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

The organization, which includes exact and natural sciences as well as the social sciences and humanities, is committed to disseminating the knowledge and values of science, fostering improvements in the quality of education and raising the profile of science in the various spheres of Mexican national life.

In her letter of nomination, Rodriguez described how Velez-Ibanez “has addressed issues that are … nothing more than the will to live, to succeed and to succeed in the midst of the most profound ecological, economic, political and cultural hardships. He has observed in a fine and profound way the cultural resources and financial strategies with which study subjects have faced the precariousness of their world … [and] has contributed in an outstanding manner to the formation of human resources for Mexicans both from [Mexico] and [the United States].”

She ended the letter, “The sole idea of his entrance to the Mexican Academy of Sciences appears to me to be an act of wisdom.”

The contributions referenced by Rodriguez include the publication of several books — four of which are based on original field research — including the forthcoming “Visiones de Acá y de Allá: Implicaciones de la Política Antimigrante en las Comunidades de Origen Mexicano en Estados Unidos y México” ("Visions of Here and There: Implications of the Anti-immigrant Policy in the Communities of Mexican Origin in the United States and Mexico"), on which she had “the enormous privilege of working with him.”

A longtime proponent of the importance of interdisciplinarity in the sciences, Velez-Ibanez is pleased to count himself among the small but growing handful of social-science experts in the academy.

“I think for too long we have thought that the cognitive processes engaged in [social sciences and hard sciences] are so entirely different that they’re not mutual. The fact of the matter is ... they’re both asking the same basic questions; they’re both asking the big ‘why’ questions,” he said.

“The problem has been that we have so over-professionalized both, and have acquired such unclear language for each. One, too many times posing as the only way in which to conduct research. The other one using language that at times is so obfuscating that it revels in its verbiage. And so, instead of moving toward clarity — which is what the scientific enterprise and the humanities enterprise is about — many times we obfuscate each other’s objectives and goals.

“Each provides us insights into the universal condition, and so shouldn’t be obfuscated by differences in language. Rather, we should try to bridge between those, because each provides invaluable knowledge to our human condition. It’s just that simple.”

Carlos Velez-Ibanez shows business entrepreneurship sophomore Briana Juarez a photograph of his father from 1916 before placing it in the Day of the Dead altar at the School of Transborder Studies on Oct. 29.

Happily, Velez-Ibanez can point to the many departments and institutions at ASU, his own School of Transborder Studies among them, that strive to do just that.

In regards to this newest distinction, he is honored but says he doesn’t expect it to affect his work, and for good reason:

“All human beings have punctuating points … I regard this as a punctuating event for me. It’s very important for me personally … [but] it doesn’t change anything at all.

“All of these things, these kind of professional punctuating points are fine, well and good, but that’s not why you do it. That stuff comes as the aftermath of whether what you do is of any value or not. It’s not the other way around; you’re not doing it for that. If you’re doing it for that, the work will suffer from your own silly ego. You just want to make a little bit of a difference. And if you can make a little bit of a difference, whether it’s in your teaching, or it’s your research, or whether it’s in some kind of public effort having to do with what you know, that’s what makes it worthwhile.”

More Arts, humanities and education

New architecture program teaches students how to design with Indigenous principles in mind

Imagine a Tempe Town Lake free of concrete, its banks lush with native creosote and wildflowers, with winding dirt paths.That visualization was created by a student who applied Indigenous principles…

Dual-language psychology program at ASU shows the importance of cultural context

Context matters — even in as seemingly a straightforward situation as quitting smoking.A recent discussion in an Arizona State University graduate psychology course delivered in Mandarin showed…

ASU course explores culture through an interdisciplinary lens

When Razieh Araghi joined Arizona State University in fall 2025, she wanted to show students the power of humanities. Her course — SLC 202 Exploring Cultures: Words, Images, Stories — aims to do…