Editor's note: Leading up to Homecoming, we'll be running several stories a week on ASU alumni. Find more alumni stories here.

A chance encounter with a gopher snake at the age of 12 was all it took to turn Christina Akins on to “herpsShort for “herpetofauna,” which are amphibians and reptiles..”

Now, the 2008 School of Life Sciences grad spends her days searching out frogs, snakes and other reptiles in the “remote and rugged mountain ranges of Arizona” as a wildlife specialist with the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

Akins was recently featured in an Arizona Highways story called “Getting Her Hands Dirty,” something she’s not afraid to do, frequently digging in hillside ponds or wading through vegetation all in the name of wildlife preservation.

Though she’d rather be active outside, the nature lover took some time out to talk with ASU News about how the university helped get her where she is today and what people need to know about wildlife extinction.

Question: At what point in your life did you know you wanted to pursue a career in biology?

Answer: My Opa and Oma (grandparents) built a cabin near the Mogollon RimThe long, steep cliff that forms the southern limit of the Colorado Plateau. when I was a small child. I grew up spending time at our family cabin, looking for fossils, catching tadpoles, etc. When I was 12, I was driving up with two of my uncles and we stopped for a large gopher snake on the dirt road. They picked the snake up off the road and let me hold it — I think that's when I began to have an interest in herps.

Q: How has your experience at ASU helped to put you in the position you are in today?

A: One of my college professors, Stan Cunningham, was instrumental in landing me a position within the Arizona Game and Fish Department. Stan worked for the department for many years prior to teaching at ASU, which allowed for his students to receive hands-on experience related to wildlife management and conservation and research activities the department was engaged in. It also allowed for us to build networking skills and connections with department staff. He encouraged me to apply for the department's internship program and, since I was one of the only students interested in herps, he thought I would be perfect for the Amphibian and Reptile Program. I became an intern for the Ranid Frogs Project in 2007 and have advanced within that project ever since.

Q: What is your favorite part of the work you do today?

A: My favorite part would be spending time in the remote and rugged mountain ranges of Arizona that most people don't have the opportunity to see. As a biologist working with amphibians, I survey and monitor frog populations in remote plunge-pool canyons, springs, "sky island" grasslands, and higher-elevation mountains ranges. Being outside is the best part.

Q: In your recent Arizona Highways feature story, it talks about how you are leading endangered-species recovery initiatives. Why should the general public care about species becoming extinct?

A: It's important to remember that we, the public, are stewards of Arizona's wildlife and each species holds intrinsic value. Because we are the stewards, we need to protect and preserve all wildlife species and their habitat for future generations. At the very least, outdoor activities bring people together, whether it's hunting, fishing, camping or a wildlife viewing opportunity. In addition, these activities bring economic value to the state to Arizona.

Q: What should they know about how it could negatively affect them?

A: Extinction does happen naturally; however, because of human impact (habitat loss, movement of invasive species, pollution, climate change, etc.) we may be speeding the rate of extinction of some species. The loss of one species from an area could have negative consequences for the larger ecosystem. Additionally, we rely on wildlife species and habitat more than we think. Plants and animals play a significant role in medical research. Many medicines we rely on are derived from plants or animals. Even species native to Arizona have contributed to this type of medical research; saliva from Arizona's only venomous lizard, the Gila monster, has been used to create a drug to help type II diabetes patients.

Q: What advice would you give to aspiring biologists?

A: The best advice I can give to students pursuing a degree in biology or ecology is to volunteer for wildlife agencies or the like. The best way to get experience and "get your foot in the door" is to volunteer or be part of an internship program. Take initiative, ask questions and be passionate about what you do.

More Science and technology

Podcast explores the future in a rapidly evolving world

What will it mean to be human in the future? Who owns data and who owns us? Can machines think?These are some of the questions pondered on a newly launched podcast titled “Modem Futura.” Co-…

New NIH-funded program will train ASU students for the future of AI-powered medicine

The medical sector is increasingly exploring the use of artificial intelligence, or AI, to make health care more affordable and to improve patient outcomes, but new programs are needed to train…

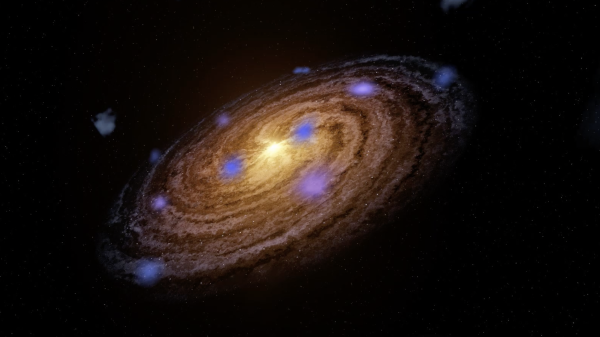

Cosmic clues: Metal-poor regions unveil potential method for galaxy growth

For decades, astronomers have analyzed data from space and ground telescopes to learn more about galaxies in the universe. Understanding how galaxies behave in metal-poor regions could play a crucial…