If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, ASU's Listen(n) project will tell if it makes a sound

“Here’s a question for you,” said Garth Paine. “How often does a plane fly over Joshua Tree?”

It’s an odd query about the national park 140 miles east of Los Angeles, halfway between the California coastline and the Arizona border, as it isn’t the kind of place people typically plant themselves for days or weeks to study air-traffic patterns.

But Paine, a senior sustainability scientist, asks it because he wants to share what it sounds like when an airplane flies over a desolate chunk of Joshua Tree’s nearly 800,000 acres of protected wilderness.

The park is one of seven desert areas that Paine and a team of researchers are studying as part of Listen(n) — a multi-disciplinary project to document and engage with the sounds of national parks and reserves in the American Southwest.

The team has collected surround-sound field recordings in these environments since 2013. Their audio makes up one of the largest online databases of its kind, which is free and publicly accessible online. They plan to grow it over the coming decades by equipping park visitors and their local communities with tools to capture and respond to the acoustics of each place.

“We really think our project will raise environmental awareness and then eventually lead to nature stewardship,” said Sabine Feisst, ASU professor of musicology and senior sustainability scholar.

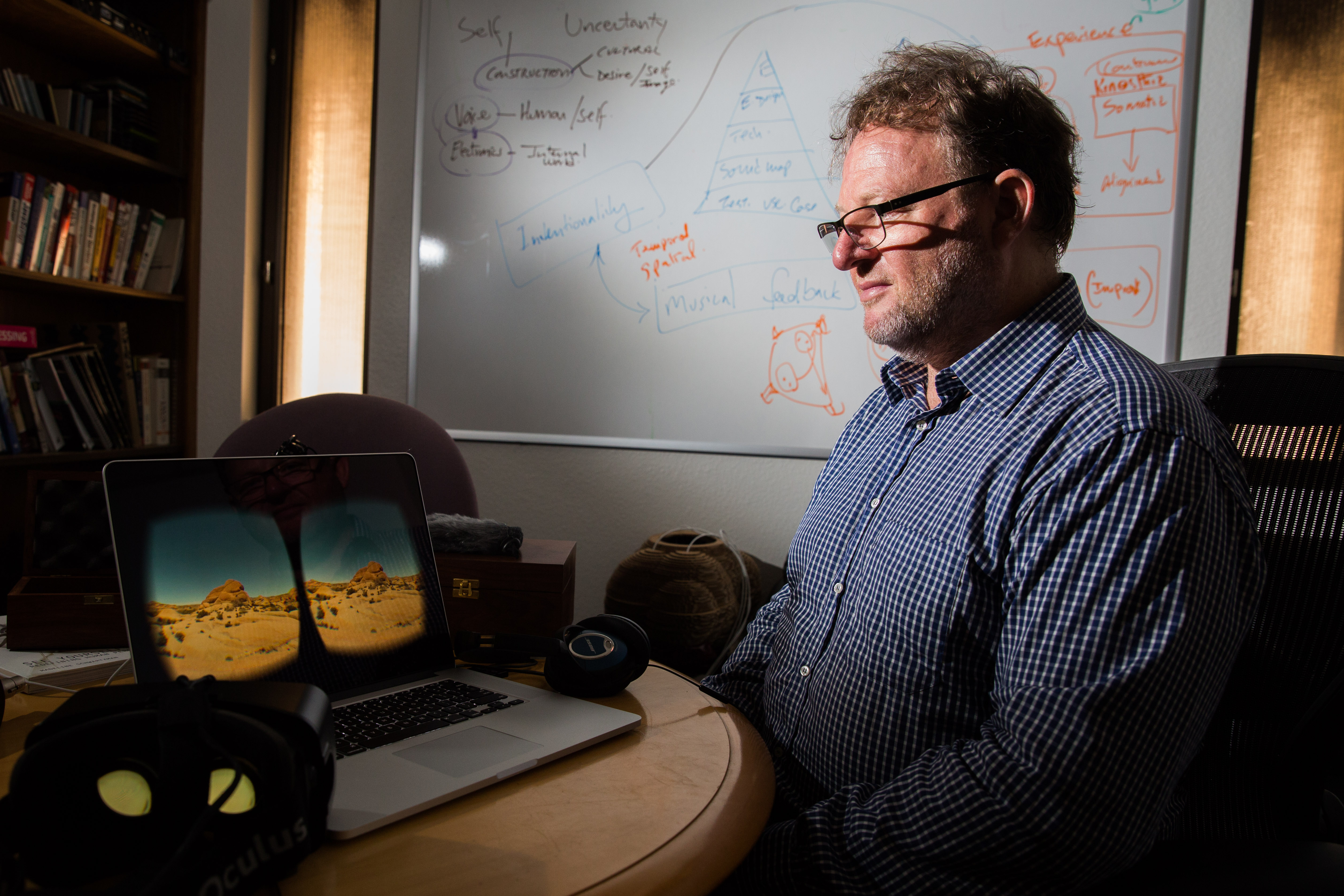

Arizona State University associate professor Garth Paine demonstrates his Listen(n) Project utilizing an Oculus Rift 3D headset and the 3D microphone he developed to record sound in three dimensions. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

According to the researchers, who also include associate professor of German studies and information literacy and senior sustainability scholar Daniel Gilfillan and visiting scholar and artist Leah Barclay, a change in the sonic makeup of an environment can indicate changes to the plants and animals that inhabit it.

Gilfillan cites a study about urban robins that sang during the day; when man-made noise production increased in their space, they shifted their behaviors and began communicating only during the quieter nighttime.

“Whatever the makeup of the landscape, it generates an acoustic container that colors everything in it,” Paine said. “So if you then come in and clear that landscape, that acoustic property is therefore cleared and the context is completely taken away and everything therefore changes.”

The Listen(n) team developed a new, spherical audio technology to precisely record those changes. With the 3-D format, they are able to match the angle from which a sound is recorded with 360-degree visual images enabled by an Oculus Rift headset to create what they call the “EcoRift experience.”

The experience, which was introduced at the 2014 South by Southwest-Eco conference in Austin, Texas, presents a virtual-reality sensation of being in the desert. As users turn their heads to see the landscape, the sounds change to represent corresponding spatial shifts in pitch or resonance.

The researchers hope the experience will encourage visits to the parks and provide access for the elderly or mobility-impaired, especially as virtual reality becomes ubiquitous.

They are also discussing with park rangers the idea of capturing the sights and sounds of protected areas that are normally off-limits to guests.

Engaging people to better understand their relationships with a place, and their agency within it, is closely connected to the Listen(n)team’s fieldwork: They offer listening workshops in collaboration with national park administrators and community organizations near their research sites in Joshua Tree, Death Valley and Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks and in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

“One of the most inspiring things is when we did one-day workshops during National Park Week,” Paine said. “When you give the kids a microphone, a recorder and a pair of headphones, they are just blown away. I’m endlessly dumbstruck by how they direct attention and really investigate.”

To encourage discourse, the team created a digital resource for storytelling, mapmaking and art related to environmental changes within soundscapes.

On Oct. 16, they will present an additional aspect of their research as they debut three of five musical works derived from the field recordings of the Listen(n)project that feature leading composers in experimental sound.

“When you give the kids a microphone, a recorder and a pair of headphones, they are just blown away.

— Garth Paine, ASU Senior Sustainability Scientist

At times, the compositions reflect the silence of a solitary land. At others, they amplify an eagle’s call, the start-stop chirping of tree frogs or winds gusting through dried shrubbery. They also contain the distant hum of highway traffic, the reverberations of a vending machine and the rattling of power lines.

And, of course, the relentless sounds of jet engines overhead, bisecting the open sky on the flight path from Los Angeles International Airport — exactly once every 30 seconds.

The Listen(n) project is supported in part by a seed grant through ASU’s Institute for Humanities Research (IHR). IHR seed grants advance faculty research with the aim of improving the quality of proposals to external funding agencies and by benefiting a wide community through public programming that features their scholarship.